Chikankari Embroidery: Painting with the Needle

Editor’s note: This is an abridged version of a story that was first published on The Heritage Lab—a media platform and wonderful resource of stories of cultural heritage, art, museums and lots more. You can find other interesting stories over at their website.

The muted, yet magnificent Chikankari of Lucknow has stood the test of time. The embroidery, treasured by yesteryear royals and contemporary designers alike, is a reflection of aesthetic choices, craftsmanship and inventiveness over the ages.

There are some speculations though, about the origin of Chikankari embroidery. The word ‘chikan’ is derived from the Persian ‘chikin’ or ‘chikeen’, meaning beautifully embroidered fabric. One set of narratives attribute the name to a distorted version of ‘chikeen’/’siquin’—a coin worth four rupaiyya, the fees paid by the Mughal Empress Nur Jahan to Persian artisans for the first embroidery. Some other accounts trace the origins of Chikankari to East Bengal where the word means fine or delicate.

There are also references to embroidery similar to chikan work in India as early as 3rd Century BC. The Greek Ambassador of Seleucus Megasthenes mentions (in his observation of the King Chandragupta Maurya’s court) flowered muslins embellished with precious stones worn by Indians. Cultural historians have cited King Harsha’s (7th Century AD) preference for white embroidered muslin “…lack[ing] any colour, ornamentation, or anything spectacular to embellish it” to establish Chikankari’s roots.

Nur Jahan and the Mughal patronage of Chikan embroidery

The Mughal Empire was at its pinnacle during Jahangir’s reign (1605-1627). Both Nur Jahan and Jahangir were great patrons of art. Empress Nur Jahan is credited with significant contribution to textiles, notably her involvement in introducing silver-threaded brocade (badla), silver-threaded lace (kinari), and, most famously, chikankari to the Indian subcontinent.

Reputed to be a skilled embroiderer, Nur Jahan designed intricate Indo-Persian embroidery patterns, sometimes inspired by Rajasthan and sometimes by Kashmir, and often mirrored Mughal architecture. She is said to have brought Persian artisans into Awadh entrusting them with the responsibility of sharing their knowledge with local families.

Embroidery was done on undyed white shazaada cotton or Dhaka ki mulmul, which was sourced from the Mughal Empire’s eastern ends. Fabric lengths were mostly utilised for dupattas at the time. As the artisans, mostly women in purdah, began to find a regular source of income, the skills and secrets were passed down generations.

Jahangir’s patronage and support extended the knowledge of Chikankari throughout modern-day India. But even as it became a favourite among the Mughal elite across the subcontinent, Awadh remained the home of the art.

Decline and then a revival

Chikan had begun to fade from public memory after Nur Jahan’s demise. It was resurrected in the 1830s under the rule of Nasir-ud-Din Haidar, the second King of Awadh and an anglophile. The embroidery was presented at darbaars and popularised by the king’s extravagant presents to the British and moved on from embellishing dupattas to other garments, including the then evolving gharara (long skirt) worn by women as well as kurtas and panels of the dopalli topi (twin-panelled cap) worn by men.

During the colonial era, the use of Chikankari embroidery increased dramatically, and embellished items exported to Britain ranging from muslin dresses, collars, table covers, and runners to mats, napkins, and even tea covers!

A painstaking process

Chikan commonly integrates motifs from Mughal architecture and designs. Among the many patterns and designs found in chikankari embroidery are muree (knotted work), phanda (loop to form a knot), lerchi, keel kangan, and bakhia (shadow work). Originally a white-on-white needlework form, the preferred fabric for Chikan was muslin or mulmul since it was most suited to the warm, slightly humid climate. Fabrics such as chiffon, muslin, silk, organza, net, cotton, and others are now widely used.

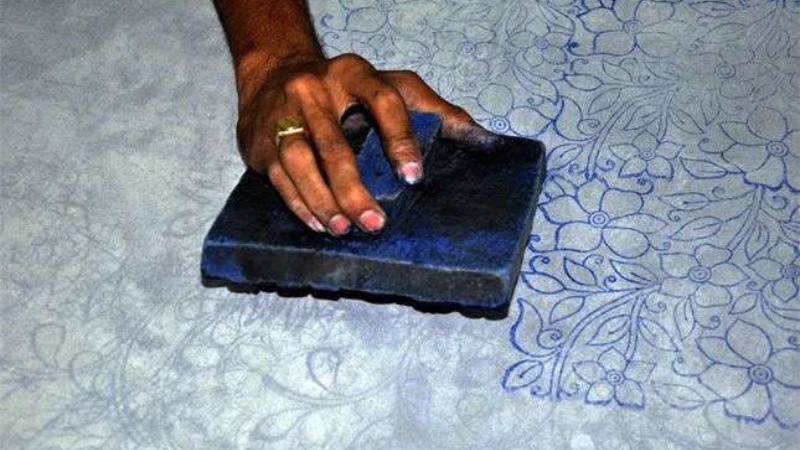

The end-to-end process of embroidery is time consuming and laborious. It is a three-step procedure of block printing, embroidery, and washing out. The initial step in block printing is to decide on a design and then engrave it onto a wooden block. These blocks are then dipped in dyes or Neel and stamped on the embroidered fabric.

Next, comes in the needlework, which is embroidering the printed design. The cloth is secured into frames because the embroidered work is more complex and time consuming than the previous procedures. Depending on the fabric and pattern, the artists create the design using a variety of stitches. The method of washing the fabric is the final step. The fabric is soaked in water for a while before being thoroughly washed to eliminate any traces of ink.

A resilient art, Chikankari has survived centuries. Instilling an air of understated elegance and grace, it is a magnificent hand embroidery that is world over for its nuanced allure and ebullient texture. Over the years newer designs and styles have come up but the magic and lyricism of the white threaded embroidery has remained the same.

souk picks

souk picks