Hiroshi’s artistic odyssey: India edition

Written by: Advisory editor Sooraj Rajmohan

I recently stumbled across a stunning series of prints created by Japanese artist Hiroshi Yoshida during his trip to India nearly a century ago. This led me down the rabbit hole of Japanese art in the 20th Century and inspired me to write about Yoshida, his life’s work, and the fascinating world of woodblock printing.

Ok, tell me about Hiroshi Yoshida…

Yoshida is one of the greatest practitioners of the style of art called shin-hanga—which literally means ‘New Print’. The wood print movement of the early 20th Century peaked between 1915 and 1942, pioneered by the legendary Shozaburo Watanabe—who was determined to revive the traditional art of ukiyo-e:

In Japan, from the 17th century onwards, woodblock printing, particularly a style called ukiyo-e, meaning ‘images of a floating world’, was a popular commercial art form. Prints were used widely in advertisements for actors and merchants.

Shin-hanga, in comparison, was a “luxury product”—created with natural dyes and traditional methods—but influenced by Western techniques of painting. For example, this 1924 print titled ‘Dancing at the New Carlton Hotel, Shanghai’ by artist Koka Yamamura:

About those woodblock prints: They were created as a collaboration between an artist, a wood carver, a painter, and a publisher/financier, though typically only the artist and publisher received credits for the work. The process required the artist to give the drawing to the carver on a fine paper, which was pressed onto a woodblock and rubbed with oil before being partially peeled away, leaving a near-translucent image on the block that the carver could use as a guide. The carver would then cut away the blank areas of the artist’s image, leaving their lines as raised sections that the painter could then imbue with colour. These blocks would be coloured in different shades and pressed to paper multiple times, with the colours varied as required each time to achieve the final output.

Shin-hanga and the original ukiyo-e both follow this production method, though shin-hanga works like the ones Yoshida created would often require up to 60 colour prints to achieve the desired result, as opposed to simpler ukiyo-e prints which would need around 20. Shin-hanga’s reliance on multiple parties to produce the image also deviated from the sōsaku-hanga style that was popular at the time, which decreed all the work—including block-making and printing—be done by the artist.

The rise of Yoshida: He trained in oil painting in the Western style, and by age 23, had already travelled to the US and had an exhibition at the Detroit Museum of Art. He did not become a practitioner of shin-hanga until the age of 40—when he was drawn into a collaboration with the great Watanabe. Yoshida’s own shin-hanga art style derived a lot from Impressionism in that it often featured the effects of light as a prominent feature. (Ironically, Impressionism itself is believed to derive from the Japanese ukiyo-e style, so make of that what you will). Besides being an artist, Yoshida was also a carver and printer—a master of all aspects of the craft.

In 1923, most of the work created by Yoshida and Watanabe was destroyed by the Great Kanto Earthquake. Seven years later, Yoshida would embark on his journey to the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia.

What did he paint in India?

For Yoshida and his son—who was also an artist—this wasn’t a pleasure trip: “Like many artist-travellers to India before him, he was interested largely in the commercial gains to be had from his trip and wanted to make as many sketches for sale as he could.” Many of his wood prints were turned into postcards—made for and sold to Western audiences.

The lead image is that of the ghats of Benares—captured in all their glory. Here are my other favourites from his India collection.

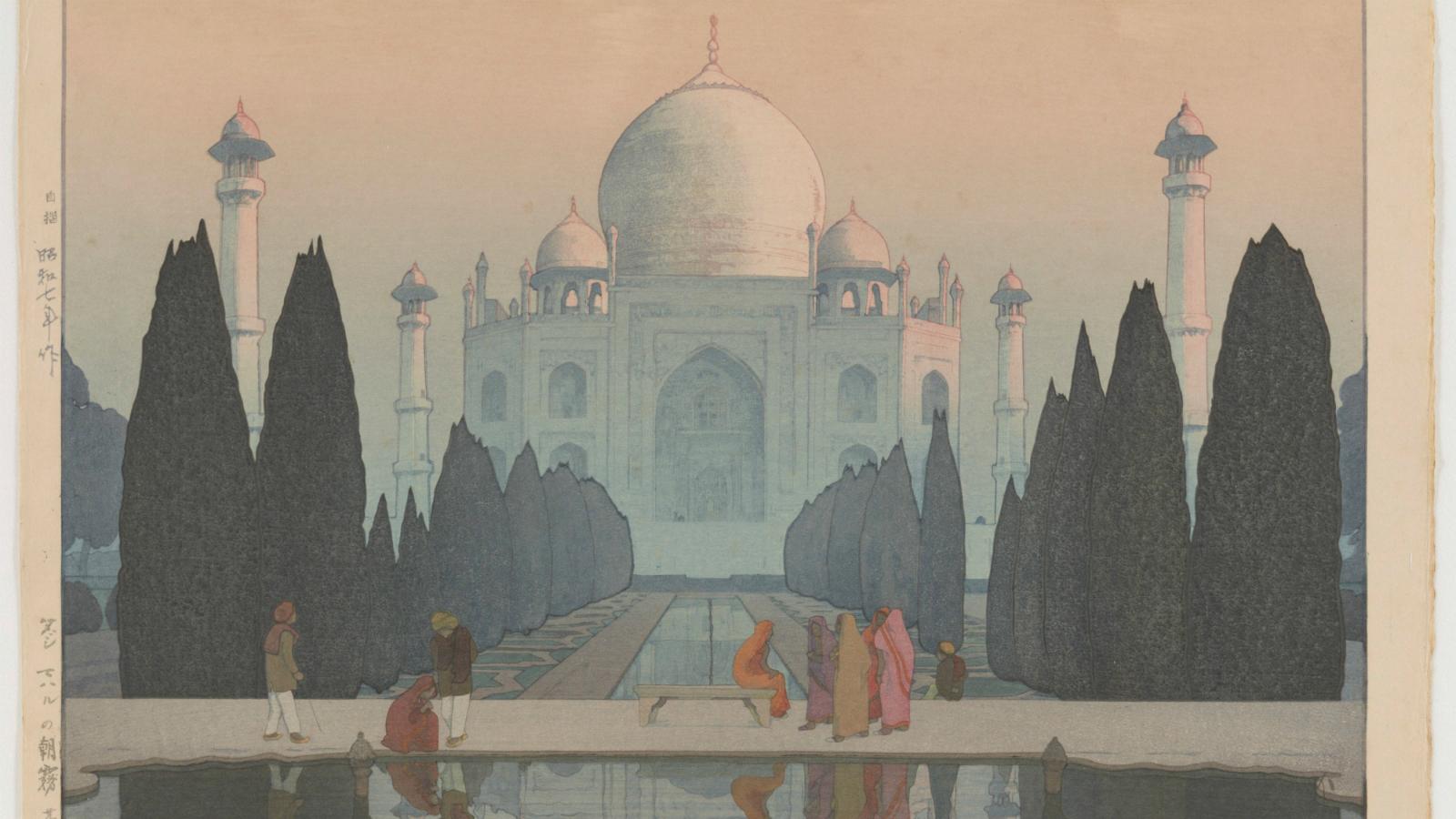

One: This one is titled ‘Morning Mist in Taj Mahal, No 5’:

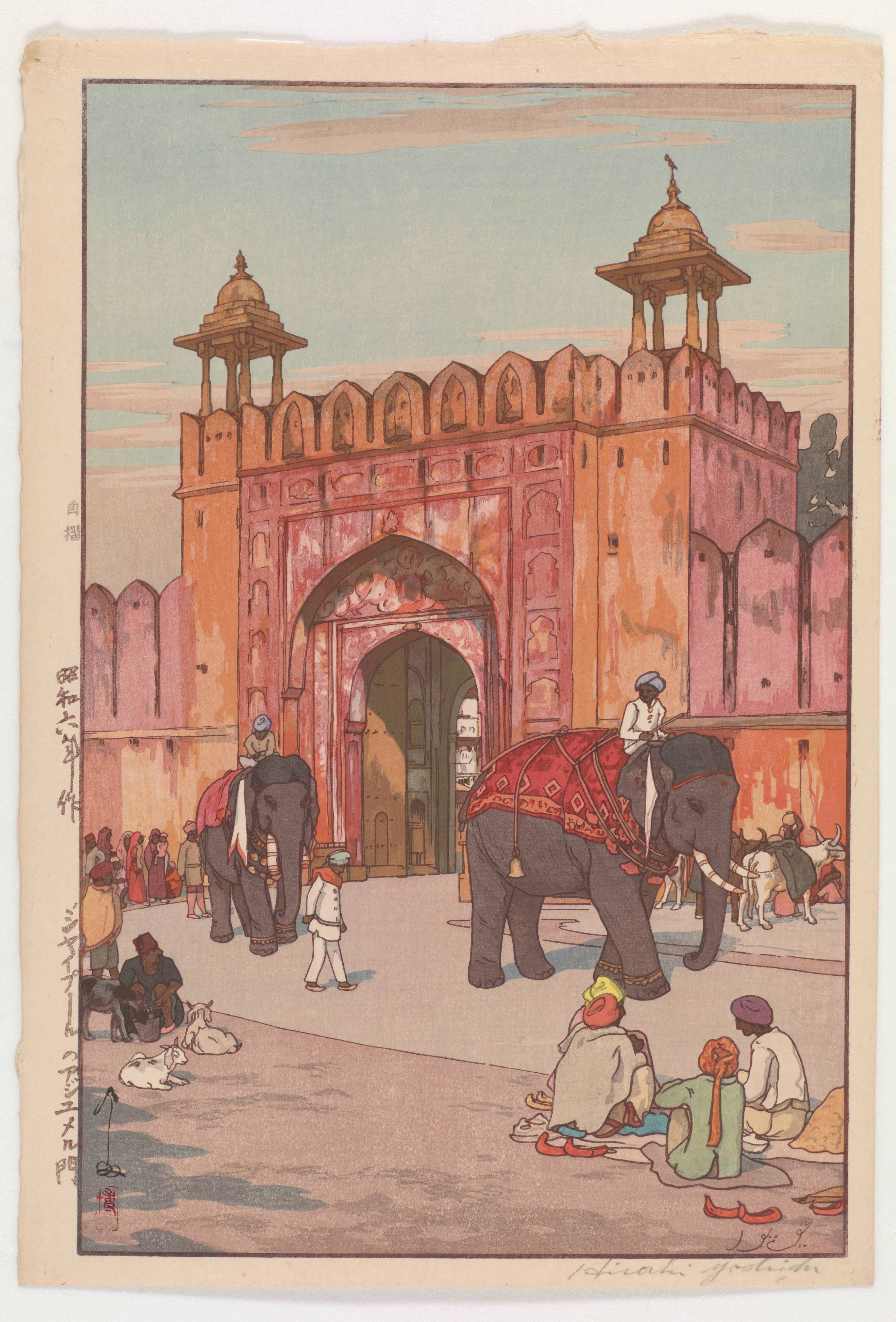

Two: Here is Yoshida’s stunning artistic recreation of Ajmer Gate:

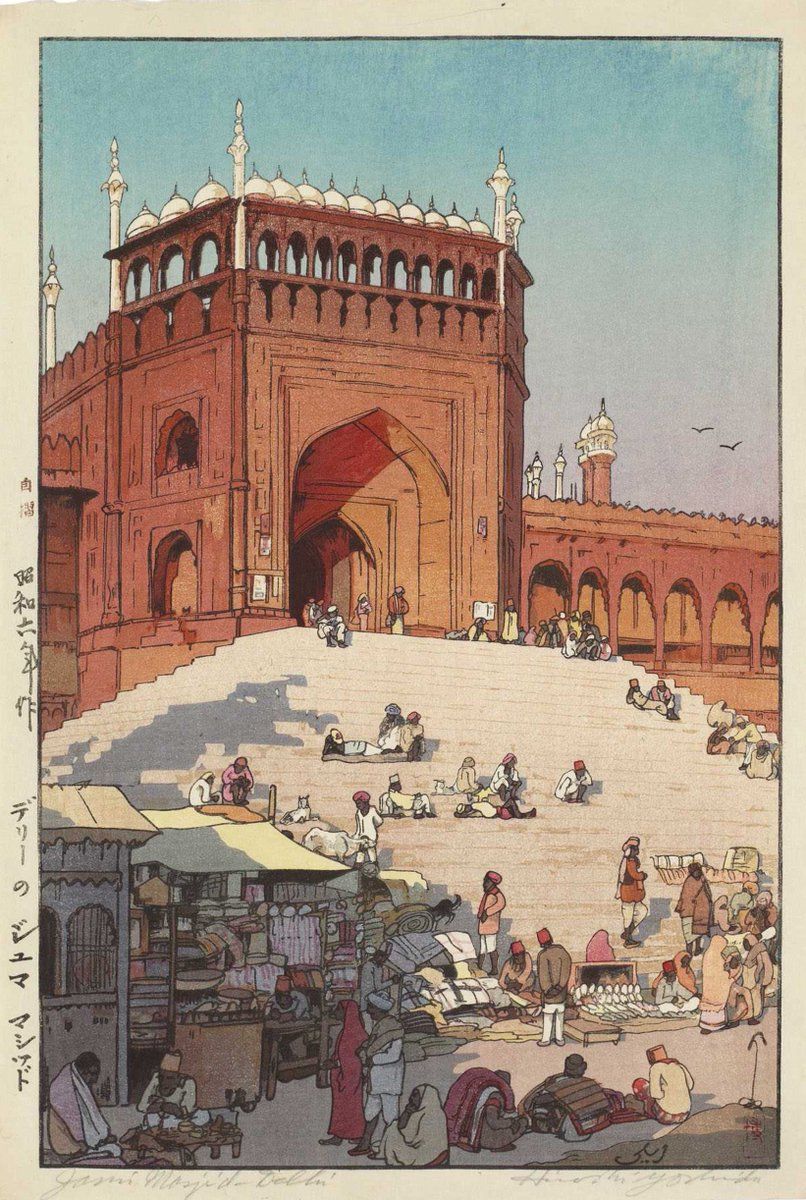

Three: This is the Jama Masjid of Delhi:

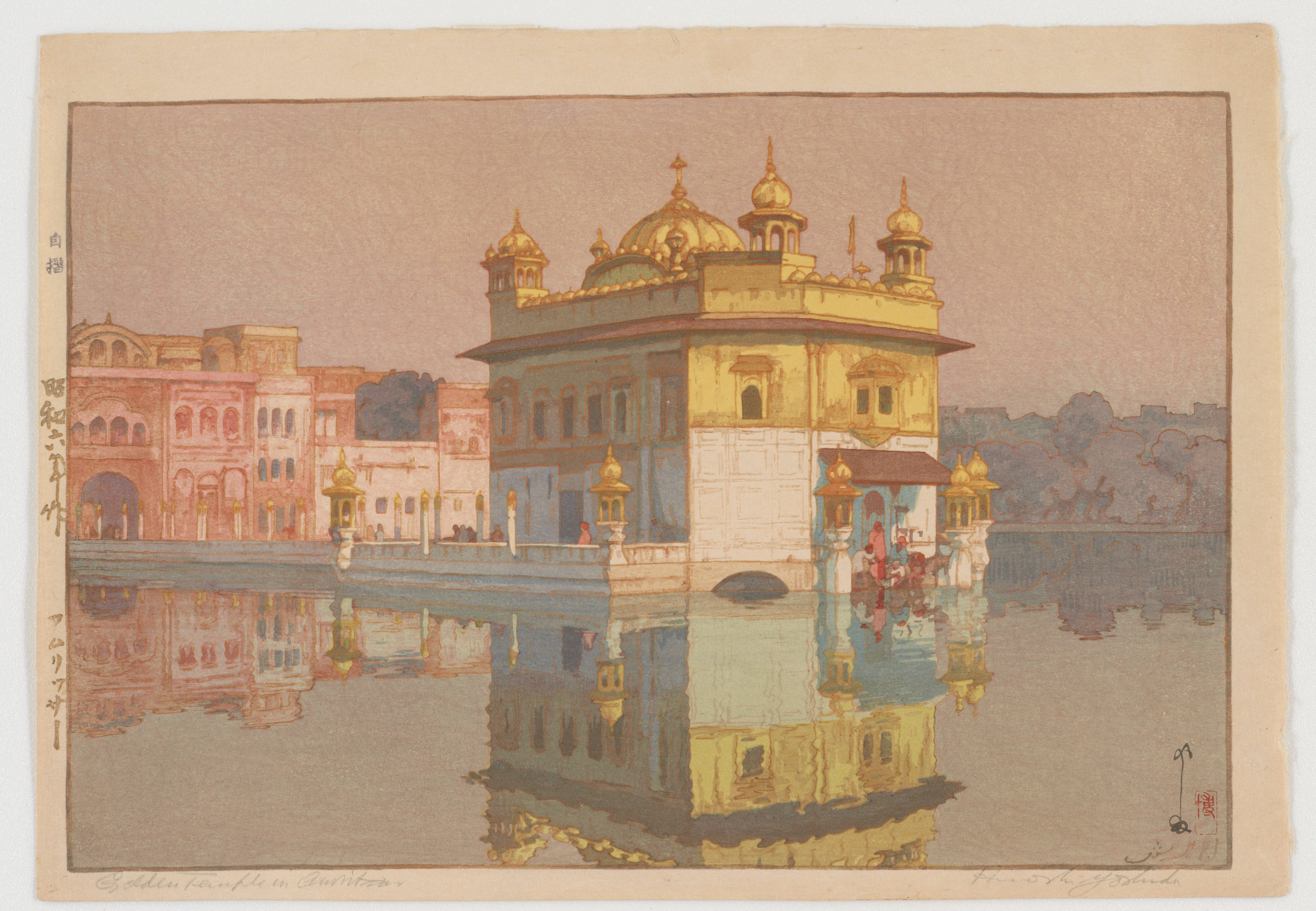

Four: This is Yoshida’s almost surreal depiction of the Golden Temple in Amritsar:

Five: Here is the Cave Temple in Ajanta:

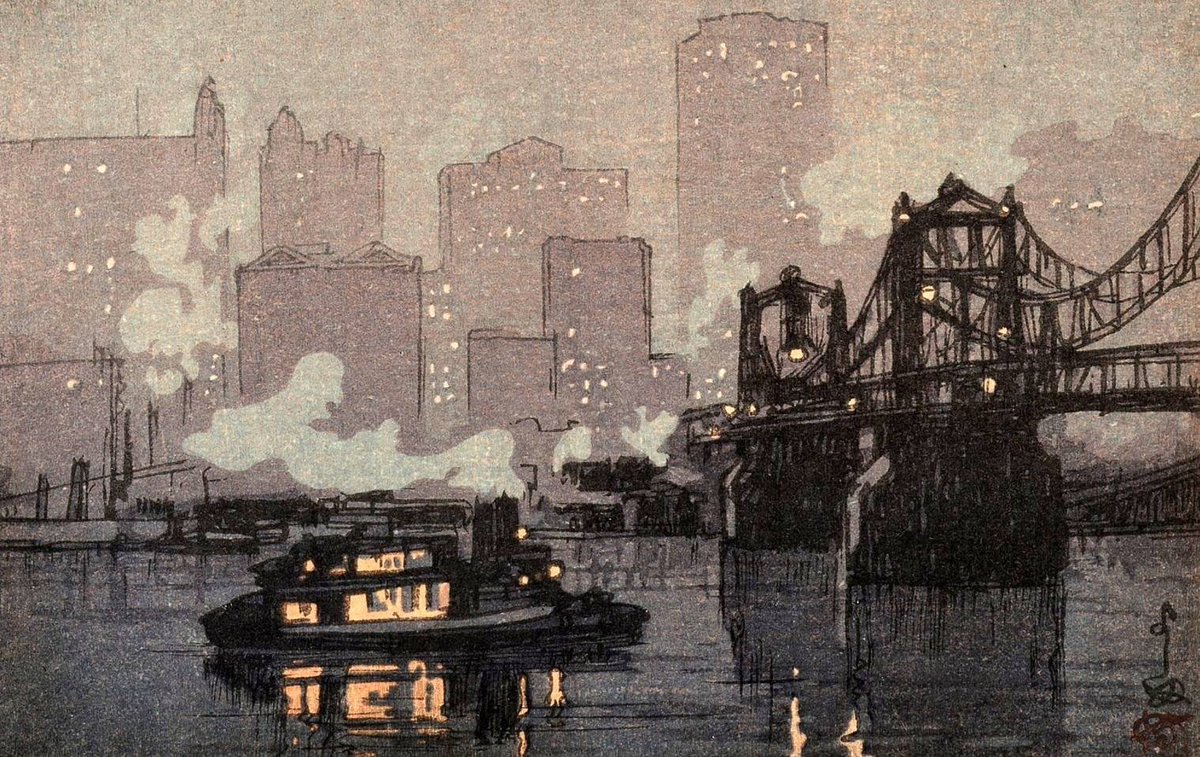

Not just India: Yoshida’s art is truly global—reflecting his travels around the world from China to the United States. Here is a magical view of Pittsburgh:

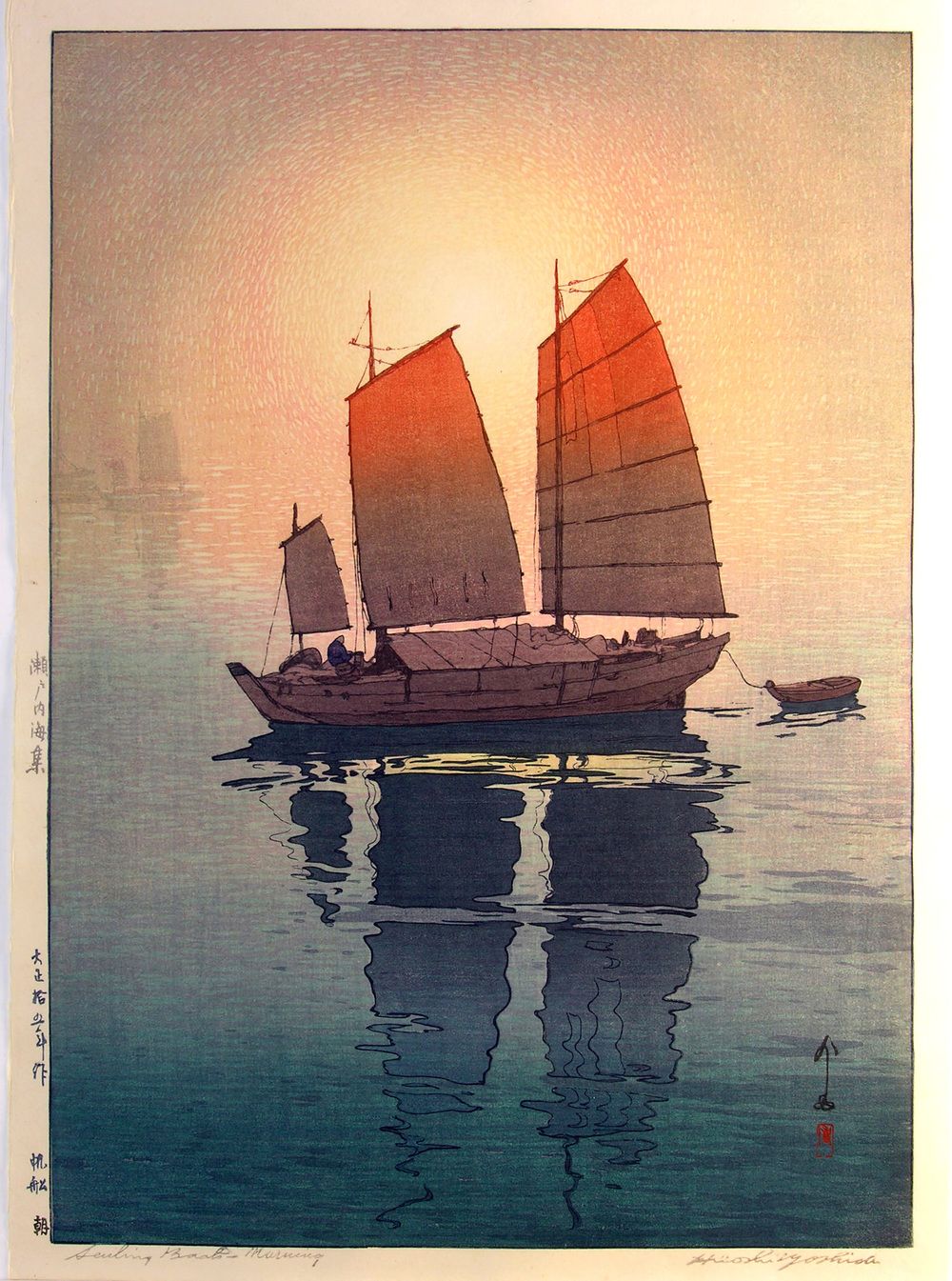

And this one of sailing boats from his series ‘The Inland Sea’:

Still want more? The Toledo Museum has a pretty substantial collection of his work already, which you can view here—or check out this ‘greatest hits’ collection:

And if woodblock prints caught your fancy, here’s an excellent video on the art:

Last not least: You can own a bit of Yoshida by picking up these postcards from Daakvaak (whom we’d recommended in the Advisory’s Buy section earlier this month).

souk picks

souk picks