A new study claims that an ancient human species—with a small brain—buried their dead. We explain why the findings are both momentous—and very controversial. If true, it may change the way we view human evolution.

Researched by: Nirmal Bhansali & Anannya Parekh

Umm, I’m really fuzzy on this evolution stuff…

As are all of us:) So here’s a basic and brief refresher.

Breaking with the apes: Around 7 million years (or 13 million) ago, the first ancient human species diverged from the apes. All the human species that evolved—and went extinct since are collectively known as hominins. The word ‘hominid’, however, includes the great apes and their ancestors. What’s notable: millions of years later, we still share 99% of our DNA with chimpanzees.

This is what the chart of human evolution looks like—pay attention to the blue bit marked “HUMANS” since that’s where the current controversy lies:

Ok, now onto the main milestones of our evolution.

Hello, Lucy: She is the earliest and best-known hominin—who lived in Africa around 3.85 and 2.95 million years ago. Her species—Australopithecus afarensis—lived for about 900,000 years. Closest to the chimps, they could live both in trees and walk upright on the ground—and had ape-like features. The discovery of her remains in Ethiopia helped us trace the origins of all humanity back to Africa—and taught us that learning to walk on two legs was the single biggest leap that helped us make the transition from ape to uniquely human. You can see the reconstruction of Lucy below:

Homo erectus: The next big jump in evolution is marked by this early human who possessed human-like body proportions, used crude implements like stone axes—and is considered to be the first human species to move out of Africa. Their remains have been found across China and Java. They lived around 1.89 million and 110,000 years ago.

Homo erectus: The next big jump in evolution is marked by this early human who possessed human-like body proportions, used crude implements like stone axes—and is considered to be the first human species to move out of Africa. Their remains have been found across China and Java. They lived around 1.89 million and 110,000 years ago.

The early humans: Soon after Homo erectus, there were a number of different human species—whose time on Earth overlapped with one another. We even mated and had babies during that time. But this time period represents a big muddle since we are still trying to figure out how many species there were—and struggling to differentiate one from another. Here are the ones we have known about for a while:

- Neanderthals lived 400,000 to 40,000 years ago and—until now—were considered our closest extinct relatives. Contrary to popular belief, they were highly evolved: “Neanderthals made and used a diverse set of sophisticated tools, controlled fire, lived in shelters, made and wore clothing, were skilled hunters of large animals and also ate plant foods, and occasionally made symbolic or ornamental objects.”

- Homo floresiensis aka The Hobbit were a small-statured species that lived 100,000 to 50,000 years ago. All their remains have been found on a single island: Flores, Indonesia. Scientists suggest that isolation and inbreeding could have caused a form of dwarfism.

- Homo heidelbergensis lived 700,000 to 200,000 years ago—and was the first human species to live in colder climates and build simple shelters out of wood and rock.

- Homo luzonensis is a recent discovery. Remains that are likely 67,000 years old were found in the Philippines. They may be the first human species to leave Africa.

The mysterious Denisovans: They are named after a cave in the Altai mountains in Siberia—where their remains were first discovered in 2010. But we have such little evidence of their existence—a finger bone, a few teeth, and a scrap of skull—that they remain an unsolved puzzle. All we know is that they spread through Asia and interbred with us—homo sapiens—and Neanderthals. But are they one species or many distinct kinds of human? With so many unanswered questions, they have not yet been classified as a human species.

Point to note: The Denisovan question now shadows every new discovery of a human species—including that of the Dragon man—whose skull was discovered in China. Is he a Denisovan or an entirely new species called Homo longi? It is one of the many debates over the hominin family tree that has not been resolved.

Homo sapiens: That would be us. We evolved in Africa 300,000 years ago as an adaptation to a period of great climate change. We share many of the characteristics of other ancient human species—but to a greater degree. For example, bipedalism—or walking on two feet for long periods of time. But what makes us a homo sapien is the size of our brain (or so scientists believe):

Modern humans have very large brains, which vary in size from population to population and between males and females, but the average size is approximately 1300 cubic centimeters. Housing this big brain involved the reorganization of the skull into what is thought of as "modern"—a thin-walled, high vaulted skull with a flat and near vertical forehead.

This big brain enabled us to invent more advanced tools and hunting techniques—and develop language and complex social structures.

The big question: The new study challenges the idea that this big brain is quite as important as we believe. And that’s why it is so controversial.

Ok, tell me about this new study…

It’s all about an ancient hominin species called Homo naledi—recently discovered in South Africa.

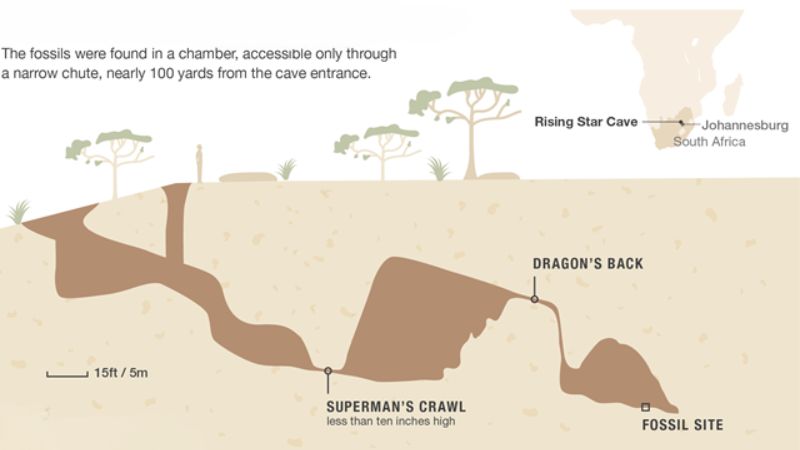

Finding Homo naledi: In 2013, two cavers crawled into an incredibly tight passage and discovered a chamber littered with fossil bones—in a location called the Rising Star cave system. Scientists identified the remains of at least 15 distinct individuals—which is astonishing:

Some scientists in this field spend an entire career finding one fragment to identify a possible new species. But early on, the team knew they had stumbled onto something extraordinary… “We found everything from infants to babies to toddlers to teens, young adults, old individuals. It is like nothing that we could have ever imagined,” says [lead scientist Lee] Berger. “Homo naledi is already practically the best-known fossil member of our lineage.”

You can see the chamber where they were found:

The basic deets: The species lived anywhere between 335,000 to at least 241,000 years ago. This means it could have met modern humans aka homo sapiens in Africa. They had a mix of primitive and modern features—and weighed 100 pounds (45.35 kg) on average and were five-feet tall. Here’s what they looked like:

The basic deets: The species lived anywhere between 335,000 to at least 241,000 years ago. This means it could have met modern humans aka homo sapiens in Africa. They had a mix of primitive and modern features—and weighed 100 pounds (45.35 kg) on average and were five-feet tall. Here’s what they looked like:

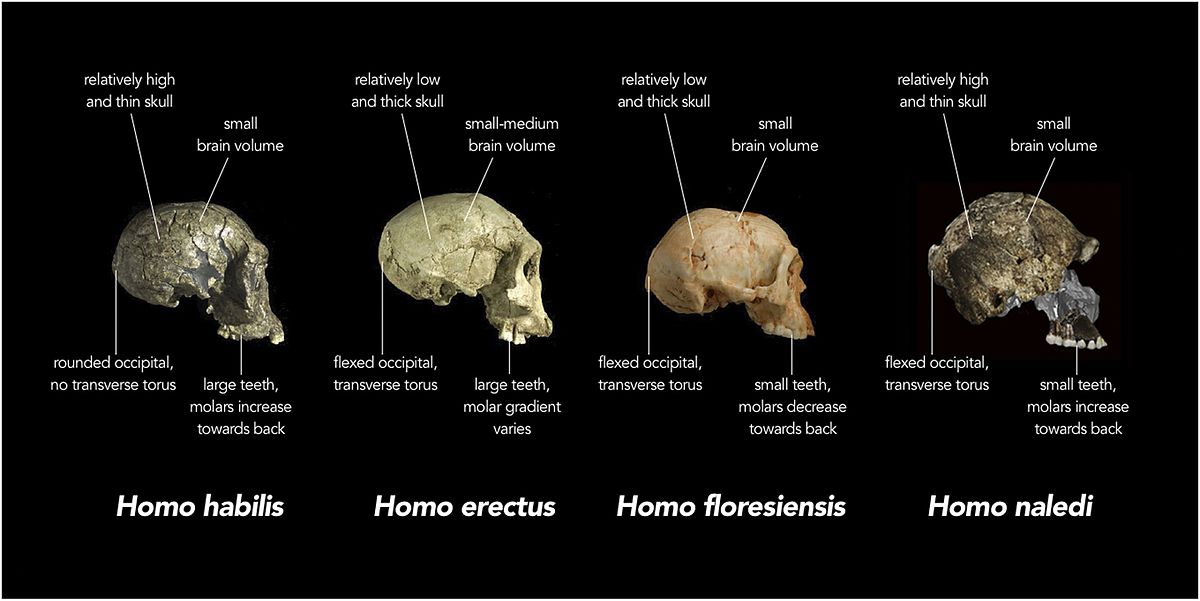

The great surprise: Their brain is the size of an orange—similar to chimpanzees—and a third of ours. See the reconstruction below:

And yet, the Homo naledi appear to have engaged in a number of behaviours that we associate exclusively with big brain-ed homo sapiens!

And yet, the Homo naledi appear to have engaged in a number of behaviours that we associate exclusively with big brain-ed homo sapiens!

One: There is evidence that they knew how to light fires. Scientists say there is evidence of extensive use such as soot, hearths and burnt bones.

Two: Berger also recently discovered engravings on the walls of the caves:

In three different areas of the walls, he saw geometric shapes, mainly composed of lines 5 to 15 centimetres long, deeply engraved into the dolomite stone. This is an incredibly hard rock, so the engravings would have taken considerable effort to make. Many of these lines intersect to form geometric patterns, such as squares, triangles, crosses and ladder shapes.

They look like this:

Why this is a big deal: “The act of engraving intentional designs is widely considered a major cognitive step in human evolution.” And these look very similar to Neanderthal carvings—which are just tens of thousands of years old.

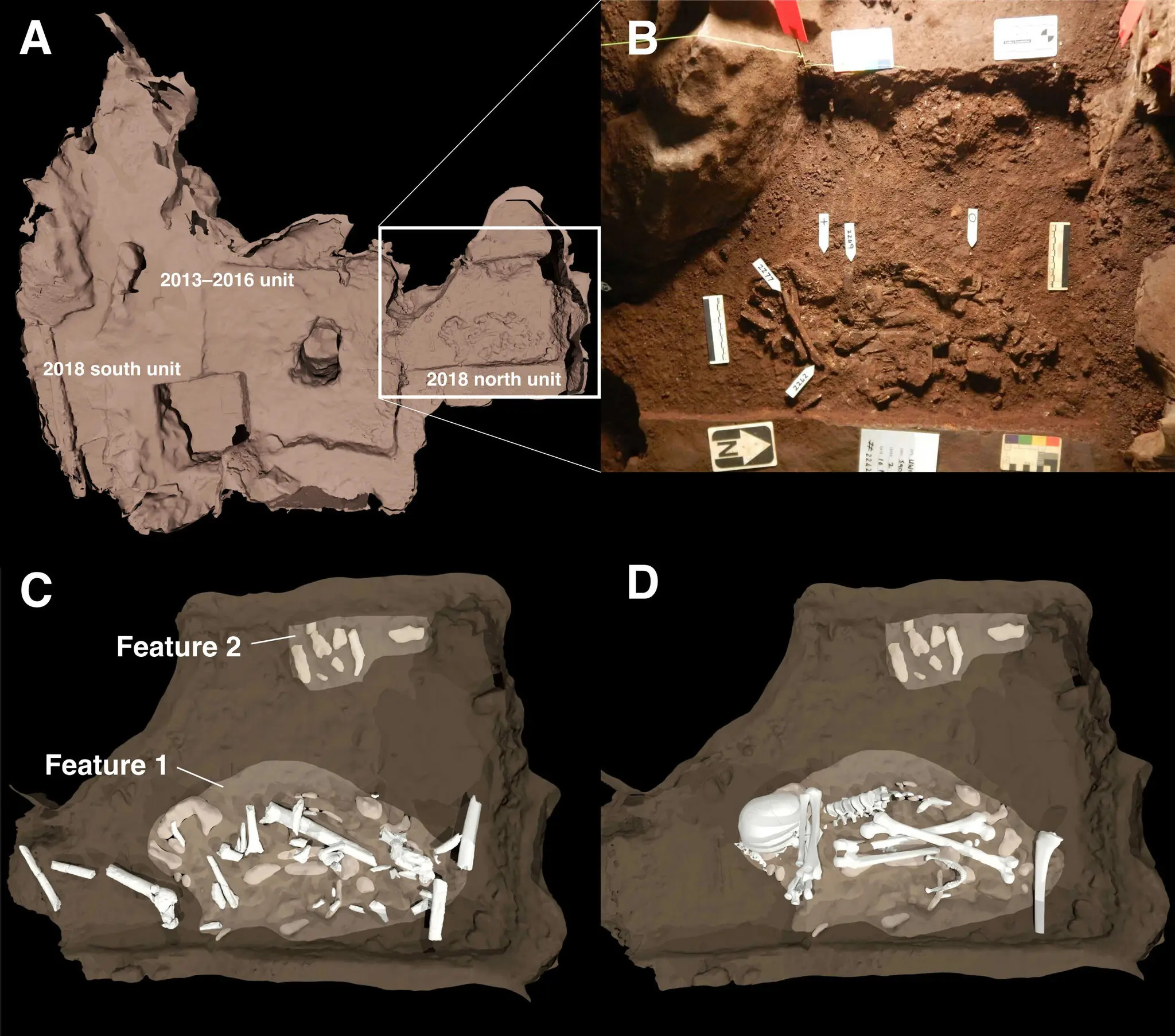

Three: Two fairly young skeletons that appear to have been deliberately buried:

“I could see the outline of this disturbed area that clearly interrupted the stable cave floor,” Berger said. “Whether you call it a grave or not, it is a dug hole with a [Homo] naledi body in it that has been covered by dirt from that hole.”

You can see their position below:

Why this is the biggest deal: Until now, the oldest known grave is only 78,000 years old. These skeletons are as much as 500,000 years old. There is a huge difference between mourning your dead and burying them:

Arguments around deliberate interment of the dead often hinge on differences between what scientists call mortuary behaviour and funerary behaviour… Chimps and elephants, for example, display mortuary behaviour when they keep watch over a dead body or physically interact with it expecting it to come back to life. Funerary behaviour, by contrast, involves intentional social acts by beings capable of complex thought who understand themselves to be separate from the natural world and who recognize the significance of the deceased.

Even Neanderthals seemed to only dispose of their dead—not bury them in a ritual fashion. As lead scientist Berger puts it: “The idea of dealing with death in ritualized fashion is actually one of the last precious things attached to being human.” That an ancient human species like Homo naledi could engage in such behaviour—despite their small brain—is truly mind-blowing.

Point to note: Some experts even view this as evidence of rudimentary language skills:

Based on the growing number of fossils scientists are finding in Rising Star, Dr. Fuentes said, it looks as if Homo naledi may have visited the cave for perhaps hundreds of generations, moving together into the dark depths to bury their dead and mark the place with art. This type of cultural practice, he argued, would have demanded language of some sort. “You can’t do that without some complex communication,” he said.

The big takeaway: If these claims are true (more on that below), then the implications are truly profound. Until now, scientists have viewed human evolution in terms of increasing brain sizes:

The fossil record shows that relative brain size in many hominin populations increased over the course of two million years, topping off with Homo sapiens. While a modern adult male brain has a capacity of roughly 1,500 cubic centimetres, Homo naledi’s brain was less than 600.

You can see a visualisation below:

Researchers argue that the Homo naledi could potentially demolish that link:

Researchers argue that the Homo naledi could potentially demolish that link:

If this small-brained hominin did in fact engage in advanced behaviours… then brain size shouldn’t be a major factor in determining whether a hominin species is capable of complex cognition… Brain structure and wiring, they argue, may have played a more important role than brain size.

The big ‘buts’: Many scientists are sceptical about Berger’s claims—and his sweeping interpretation of the evidence. For example, it is impossible to date those carvings accurately: “In theory, those rock engravings could have been made by cavers in the 1930s. They have jumped to the assumption that they were made by H. naledi.” Others say “it’s entirely possible that Homo sapiens was in these caves.” And not everyone views the arrangement of the bones as proof of a burial site. Also this:

One major point of contention has been the difficulty H. naledi would have had in transporting its dead to the cave chambers 300 feet below ground. The descent requires squeezing through passages as narrow as seven inches… “Okay, they are smaller than us, but the spaces they have to crawl through are really tiny,” [researcher Aurore] Val said. “And somehow they are pushing or dragging a dead person in front of them or behind them and doing that presumably for generations.”

The bottomline: It is far too early to tell if these claims are based in speculation or reality. The research has not been peer-reviewed as yet. Anthropologist Agustin Fuentes perhaps has the most balanced take on the discovery:

The bottom line for me is, it takes the brain away as the focus. Big brains are still important. They just don't explain what we thought they explained. That means we need to step back, take humans off the pedestal yet again, and try to understand what are the dynamic processes and what are the social and community emotional dynamics that allow this kind of complex behaviour without having this big, complex brain. We know a lot less than we thought we did.

Reading list

The original Homo naledi research is laid out in the National Geographic—which also funded the study. Ars Technica’s report may be easier to understand—and has more background on the project. CNN and Washington Post (splainer gift link) sums up the details—and objections. For a more exhaustive critique, check out The Conversation. New Yorker has a very good profile of the controversial lead scientist Lee Berger. Smithsonian and Nautilus have a good overview of human evolution. We did a Big Story on the discovery of the Dragon Man in China—and The Hindu has Nobel Prize winner Svante Pääbo’s research on the human genome.

souk picks

souk picks