Editor’s note: The Kochi-Muziris Biennale is one of the premier art exhibits in the world. But many of us don’t even know about it. Here’s a guide to the Biennale and our favourite pieces of art on display at the exhibit.

Written by: Vagda Galhotra

Wait, what is a biennale?

A ‘biennale’ is a generic term in the art world for a large-scale exhibition that’s held every two years. The ‘Muziris’ in the Kochi-Muziris Biennale is a nod to the ancient lost port of Muziris located near Kodungallur. Here’s how an ancient Sangam poem describes it:

With its streets, its houses, its covered fishing boats, where they sell fish, where they pile up rice—with the shifting and mingling crowd of a boisterous river-bank where the sacks of pepper are heaped up—with its gold deliveries, carried by the ocean-going ships and brought to the river bank by local boats, the city that bestows much wealth to its visitors, and the merchants of the mountains, and the merchants of the sea, the city where liquor abounds, yes, this Muziris, where the rumbling ocean roars, is given to me like a marvel, a treasure.

It is only fitting that it should be part of an exhibit that celebrates the marvels of Indian art. India’s first, the Biennale was founded in 2011 by Mumbai-based artists Bose Krishnamachari and Riyas Komu to “create a platform that will introduce contemporary, global visual art theory and practice to India.” This is the Biennale’s fifth edition—held again after a gap of four years due to the pandemic. It opened on December 23 and is on till April 10.

Biennales = art fairs?

No, biennales are not the same as art fairs. The goal of a fair is to sell art—in this sense, they are commercial ventures. OTOH, biennales are organised by non-profit organisations and aim to create visibility for artists, spur conversation and promote local culture. In fact, most biennales don’t allow direct sales.

The Kochi-Muziris Biennale is designed to promote local artists and tourism, and cultivate interest in the heritage and historical cosmopolitanism of the city of Kochi. This is reflected in the locations chosen as key spaces for the exhibits—they are all heritage properties, galleries, warehouses in the localities of Fort Kochi, Mattancherry and Ernakulam—such as Aspinwall House, Pepper House, and Anand Warehouse.

Also as opposed to art fairs, biennales are curated around a theme. This year the Biennale’s central exhibition ‘In Our Veins flow Ink and Fire’ is curated by Singaporean artist Shubigi Rao. It exhibits over 200 projects featuring 90 artists and 30 new commissions.

When speaking at the opening of the Biennale, Rao spoke of the simple idea behind her curation:

What happens when a group of people inhabit a space through their works? What do those works say when they are in proximity to each other? When you walk through Aspinwall House, Pepper House, and Anand Warehouse, you will see the works not just in isolation from each other, but actually speaking to each other. None of us exists in isolation. We are drawing on the works of others when we write, think, make, and speak. There is no such thing as a lone genius. That is a myth. We are all part of a collective thinking.

Point to note: This Biennale had a shaky start. It was supposed to open on December 12, but was delayed due to “organisational challenges.” The artists experienced delays in their shipment and damage to their artworks as they complained of mismanagement by the organisers, penning an open letter expressing their disappointment.

Ok, can I please see the art now?

Yes, of course:) Here are some of the artworks that we personally loved:

One: Our lead image above is an artwork titled ‘Cannot Be Broken and Won’t Live Unspoken.’ It is a take on the traditional Indian deity by Singapore-based artist Anne Samat. For her sculpture, she uses rangoli patterns drawn in India and Malaysia (her country of origin) as inspiration—along with plastic toys, textiles and tools.

Two: One of the most eye-catching sculptures at the Biennale is New Delhi-based artist Asim Waqif’s ‘Improvise’—a complex 20-feet sculpture made of bamboo, coir and pandanus leaves. The structure contains bamboo musical instruments, light-emitting objects, and a cradle where “one can lean and swing endlessly.” Waqif aims to drive home “the relevance, potential, and importance of things that are discarded in day-to-day life by people as insignificant.”

The sculpture is so big, that no one image does it any justice. You can see the cradles in the image here and a man playing the bamboo instrument here. Waqif has collated the visitors’ interactions with his sculpture in a reel on his page—you can check that out below.

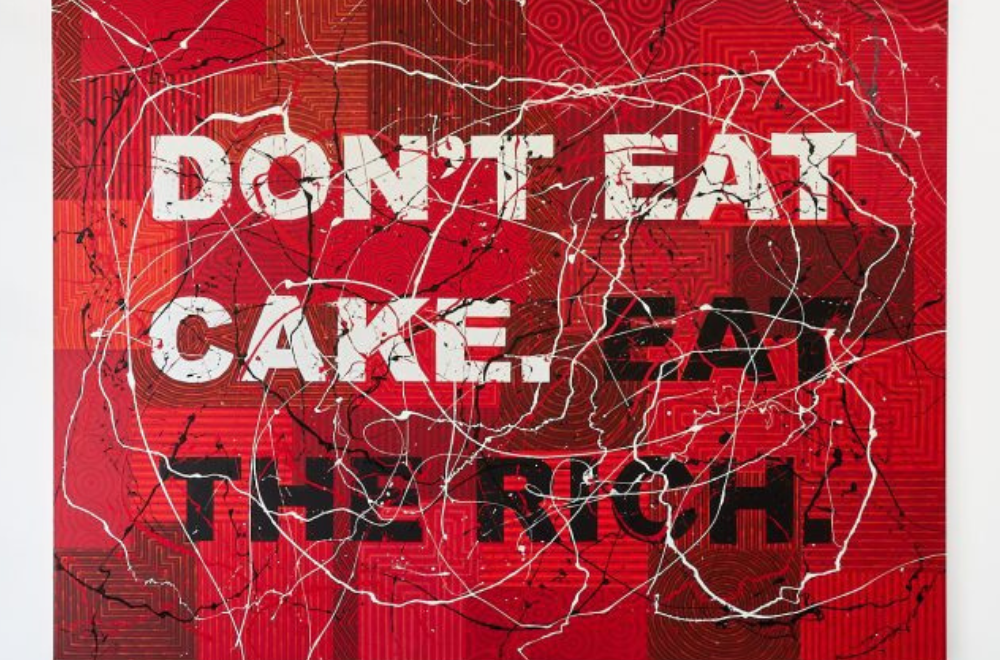

Three: For something more eye-catching and lively, see this artwork below titled ‘RICH’ by Australian artist Richard Bell—who calls himself “an activist masquerading as an artist” He uses text and pop art to raise questions against power, colonialism and capitalism. You can read more about his work here.

Four: The image below is part of a series of artworks titled ‘Brothers, Fathers and Uncles’ by Devi Seetharam. The series attempts to tackle patriarchy by capturing how men dominate public spaces in Kerala. There are lots of lovely pieces in the series, and you can check them out here.

Four: The image below is part of a series of artworks titled ‘Brothers, Fathers and Uncles’ by Devi Seetharam. The series attempts to tackle patriarchy by capturing how men dominate public spaces in Kerala. There are lots of lovely pieces in the series, and you can check them out here.

Five: This is Goa-based artist Sahil Ravindra Naik’s large-scale installation titled ‘All is Water and to Water we Must Return’. It charts and mourns the loss of Curdi and Kurpem villages–which were submerged to make way for the Salaulim dam in Goa. Again, pictures don’t do justice to the installation since the background music of Konkani local singers is part of its experience. You can get a glimpse of it in the clip below.

Six: Amol K Patil’s ‘Politics of Skin and Movement’ is inspired by the Uthapuram caste wall in Tamil Nadu—infamous for segregating the local Dalit community. Of his artwork he says, “I have tried to stage a conversation between inside and outside spaces. An L-shaped wall almost acts like a theatrical stage and it prevents you from going over to the other side.” You can check out the rest of his work on his Insta handle.

Seven: South Korean artist Haegue Yang’s ‘Sonic Droplets—Steel Buds’ is one of the international heavyweights at this Biennale. She’s created a sculpture of more than 100,000 stainless steel bells that create sounds similar to that of various secular and religious rites.

Eight: The artwork below titled ‘Palianytsia’ seemingly appears to be sliced bread but is actually a rock carved round by the river—and sliced by Ukrainian artist Zhanna Kadyrova. FYI: Palianytsia is a circular Ukrainian bread—and stands for Ukrainian hospitality. But at the time of the invasion, it also became a marker of the aggressor, since the Russians pronounce palianytsia differently. Kadyrova was based in Kyiv before the invasion.

As for the rest: beyond the main exhibit

One: Other than the central exhibition, the Biennale also has a Students’ Biennale and other satellite exhibitions—one of which is the ‘Idam’ collection which is exclusively reserved for Malayali contemporary artists. It’s up for display at the Durbar Hall Art Gallery and includes 200 artworks created by 34 artists, 16 of whom are women. It was curated by artists Jiji Scaria, Radha Gomathy and PS Jalaja. See a snippet of the ‘Idam’ collection below.

Two: We also loved this colourful work titled ‘Zobop’ by Scottish artist Jim Lambie at another satellite exhibition on display at the Dutch Warehouse. The work entails covering the floors of the venue in colourful vinyl strips in geometrical patterns that pop and bewilder all at once. Lambie uses the reference of Bebop—a style of jazz popular in the 1940s—in his use of the colourful strips to evoke “a sense of unpredictable progressions.”

Three: The Kochi Biennale Foundation also invited exhibitions from across Asia and Africa to the Biennale. One such exhibition was the Bhumi Community Art Project which was created by the residents of Balia village in Thakurgaon, Bangladesh as a symbol of human resilience and creativity. It explores themes of “indigenous farming, human-land relationships, and the socio-cultural changes in the communities using locally available materials including bamboo, straw and jute.”

Four: Another one that we found intriguing was the ‘Covering Letter’ by Jitish Kallat which is part of Kiran Nadar Museum of Art’s ‘Tangled Heirarchy 2’ exhibition curated by Kallat himself. This artwork is a seminal installation of a letter written by MK Gandhi to Adolf Hitler in 1939, urging him to choose peace. The letter is projected on a curtain of dry fog that one can pass through. The video below is from 2020 when the same was exhibited at the Frist Art Museum in the US.

souk picks

souk picks