Hayao Miyazaki, take me home

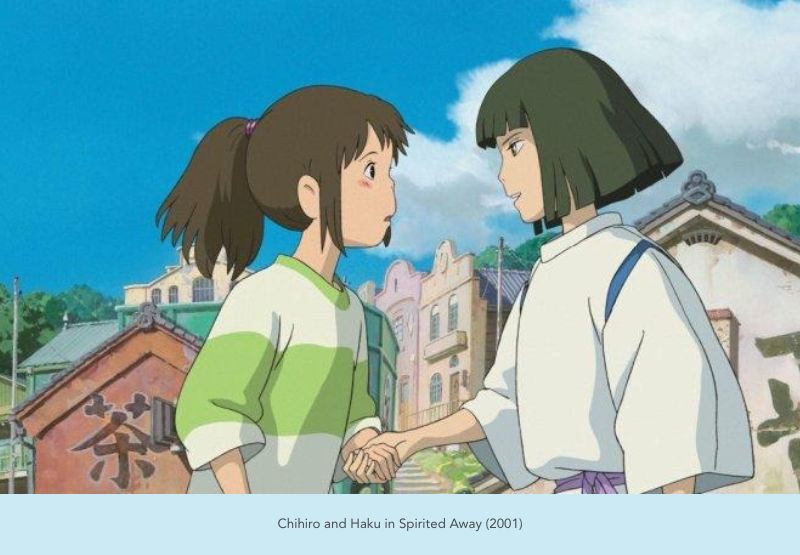

Editor’s note: Hayao Miyazaki, arguably the greatest and most popular Japanese anime filmmaker ever—and his Studio Ghibli films—have been making us giddy and teary-eyed for over three decades. His best work, including Spirited Away, which turns 25 this year, loops around vanishing childhoods, foreign dream worlds, and reconnecting with memories. In this essay simmering with longing, Washington-based Sritama Bhattacharyya makes sense of her life away from her Kolkata home through Miyazaki’s world.

Written by: Sritama Bhattacharyya

*****

In Hayao Miyazaki’s Castle in the Sky (1986), the protagonist Princess Sheeta wears a necklace. It holds a blue crystal that transmits light toward her long-lost home—the planet Laputa, floating unnoticed in the sky. As is her royal birthright, only Sheeta knows how to activate the crystal, meant to guide her home. Watching her, I found myself imagining what it would mean to carry such a crystal myself. If I had one, it would undoubtedly cast its luminance towards Kolkata—a city I return to at least once a year.

Miyazaki plays a significant role in my experience of homecoming. Born and raised in Kolkata, I moved to Washington and have been settled in Seattle since 2023. Returning home annually during Durga Puja feels like walking into a carnival that once embraced me but now politely greets me as a visitor… a guest, even, which is far worse than a visitor, who is never overwhelmed with rushed hospitality.

To be fair, I am never unwelcome. I am always given the best cutlery, the choicest piece of machh bhaja from the cooking pan. Adored to the point of being smothered, just about enough for it to feel strange.

Autumnal Kolkata glimmers with possibilities, like the enchanted theme park in Spirited Away where the knee-high heroine Chihiro gets lost, after trespassing into a ghost-ridden realm not meant for her.

Now, when I am back from the US, I float through streets luminous with puja lights, slightly estranged from the place where I spent close to three decades. The pandals; the dhak; the hoardings of soda water, incense sticks, perfumes, and garam masala powder—all carry the unmistakable scent of my one true home, to which I cannot yet return.

This is where Hayao Miyazaki’s inner world, preoccupied with the catastrophes of growing up, comes in handy. His stories are marked with impermanent homes, half-remembered identities, and childhoods slipping away. Not surprisingly, young Miyazaki kept moving between cities to avoid bomb raids in Japan during WWII. Coupled with a bedridden mother ailing from spinal tuberculosis, Miyazaki found solace and stability in his imagination.

People lose names or vanish entirely. Castles sprout legs and flee; a prince becomes a scarecrow (Howl’s Moving Castle, 2004). Soldiers get cursed and become animals (Porco Rosso, 1992). An abandoned human child becomes the daughter of a wolf goddess (Princess Mononoke, 1997). Rivers cannot remember their names (Spirited Away). All these characters are displaced from where they belonged. Miyazaki’s films echo a truth I’ve been coming to terms with lately: belonging is a fragile arrangement, grasped most clearly when you are farthest from home.

The Determined Departee

Miyazaki’s films tell us that once you leave, you must justify leaving. You must find purpose for the leaving to be worth the spectral wound that comes with separation.

When pirate leader Dola (Castle in the Sky) warns the orphan Pazu that choosing to rescue the abducted princess Sheeta will require him to leave his mining village forever, he joins the crew. Aboard the airship, he works as a repairman while Sheeta starts a new life as a cleaning lady and cook.

Sophie, in Howl’s Moving Castle (2004), after being turned into an old woman by the ‘Witch of the Waste’, has to leave home and begin working as a cleaning lady for the reclusive wizard Howl.

Kiki (Kiki’s Delivery Service, 1989), a young witch who feels forlorn in the new town she arrives in for her training, becomes a delivery worker to survive.

Even Chihiro, separated from her family that’s transformed into pigs, begs Kamaji, a multi-armed, spider-like spirit for a job, and becomes a bathhouse attendant in Spirited Away (2001).

Together, these characters vindicate the hustle that comes to define the lives of those who leave home determined to survive—come what may.

Your job applications disappear into résumé black holes, letters of recommendation may arrive too late or not at all, and you wait, ghosted, on the wrong side of rejection, still cooking, cleaning, folding laundry like clockwork, still trying to justify why you ever left home. And yet, no amount of hustle shields you from the inescapable grief of leaving home behind.

What After Home?

There is a moment in Spirited Away I have carried within me for years. After Chihiro, surviving the mystical spirit world, reminds her new-found friend Haku of his true identity—a river spirit who once saved her from drowning and guided her to shore—Haku helps her one final time, securing her freedom from the crafty bathhouse boss, Yubaba.

Haku remembered Chihiro’s name which she had forgotten, and later, she did the same for him.

On her way back home, as they stood at the edge of a meadow, Haku tells her, “I can’t go any farther. Cross that meadow and don’t look back.”

I wonder how different this is from anyone who has ever loved, standing at an airport or a railway station, seeing their love recede with a heavy heart.

You will miss the birthdays of your parents, your niece, your best friend. You will not be there at your uncle’s deathbed, when seeing you was the last thing they wanted. Life will continue; people will find joy and celebrate as they gather and clap around cakes. You will not be there for any of it. You cannot even hope that things will remain the same. No one owes you constancy, just as you did not owe anyone the courtesy of staying.

This is a hard truth that Mahito, in The Boy and the Heron (2023), is forced to swallow when his mother dies in a hospital fire. His father moves on and marries his aunt, and Mahito is made to settle into a countryside home where his mother and his aunt grew up. In Miyazaki’s world, the rupture created by the loss of home rarely ends with leaving—it reaches backward into memory, eroding something far more fragile. In his world, to lose home is to lose something that once made childhood possible.

Leaving makes grief inevitable, and grief makes leaving irrevocable.

Loss of Home is Loss of Childhood

Teenager Satsuki (My Neighbor Totoro, 1988), right after shifting to a country house, starts taking care of her sister, Mei, as their father gets busy attending to their sick mother. Satsuki cooks for the family, braids her sister’s hair, and assures her parents she has it under control. Her cracks, visible to us, don't get communicated to her closest people.

Meanwhile, young witch Kiki (Kiki’s Delivery Service, 1989) observes that flying on a broom used to be fun until she had to do it for a living. After she loses her magic, she confides in her cat, Jiji: “I meet a lot of people, and at first everything seems to be going okay, but then I start feeling like an outsider.”

This dichotomy reveals itself most clearly after leaving home. One hopes to belong—if only one could speak in the right accent and feel comfortable in one’s own skin; if only one did not have to hide one’s demons on a video call.

Yet, Hope Dies Last

There is an enduring sense of hope in the way Miyazaki turns the mundane into the spectacular.

At the start of Spirited Away, Chihiro is travelling with her parents to her new house. In the car’s backseat, she is latching onto the bouquet she received as a gift from her friend. But the flowers are dying, she exclaims. Her father had gifted her a rose, it’s pointed out. Chihiro snaps back: a rose is not a bouquet!

Applying that to life, one realises that crumbs are not bread. Spending a month in Kolkata as a guest, receiving special treatment, is not the same as truly returning. Visiting is not belonging… yet you spend months daydreaming about homecoming once you get your flight tickets. You do not invest in the house you currently live in, because to you, life is elsewhere—happening in a city where your niece cuts her birthday cake.

It also dawns on you that home left you the moment you left it.

Even if you return, you are different. The home you once knew has moved on—like Howl’s castle, shifting through different dimensions. People have learned to live without you.

You relate to the river spirit that cannot remember its name, the soldier who has been turned into an animal, the wolf princess striving to save a forest, leaving her pack behind. You are the flickering screen as the internet connection falters in a room full of real people. Like Chihiro, a human among ghosts, you are the screen among humans. An outcast, except no one has cast you out—you chose this departure, you remember. In any case, remembering is more graceful than being reminded.

*****

Sritama Bhattacharyya is a writer and teacher based in Washington.

souk picks

souk picks