There are as many Sitas as there are Ramayanas. Feminist reinventions in modern fiction often pale in comparison with these ancient incarnations—like the Sita who slayed the thousand-headed Ravana. That one was written by Valmiki himself. On the occasion of Dussehra, we revisit some of the lesser known but no less ‘authentic’ versions of the ultimate aadarsh naari.

Editor’s note: Each of the Ramayanas mentioned below are—or were—sacred to a community. We do not intend to insult anyone’s religious sentiment in revisiting the many cultural interpretations of a revered text.

The lead image: is a 1991 painting of Sita and the golden deer by MF Husain.

Adbhut Ramayana: When Sita destroyed Ravana

After the sage Valmiki completed his original magnum opus, he penned this new version of the great epic to do justice to Sita. In the telling, she is the awe-inspiring power who conquers Ravana—not Rama.

Birth story: Unhappy with her husband Ravana’s infidelity, Mandodari swallows the blood of the sages—mistaking it for poison. She becomes pregnant instead and abandons the baby/foetus in a field (mother Earth). The King Janak finds her and adopts her as his own.

The exile etc. etc.: A great part of the story follows almost the exact same trajectory as the original Ramayana. Sita is abducted, Rama rescues her—slaying the ten-headed Ravana. He returns to Ayodhya in triumph. All seems as it should be.

The other Ravana: However, one day, when Rama is boasting of his great feat to courtiers—or is being praised by sages—Sita smiles. She speaks instead of the far more powerful thousand-headed Ravana, the ruler of Pushkara—and twin brother of the demon-god the rest of us know so well. An outraged Rama sets out to conquer this other Ravana—but is overcome by his might. And he falls unconscious on the battlefield.

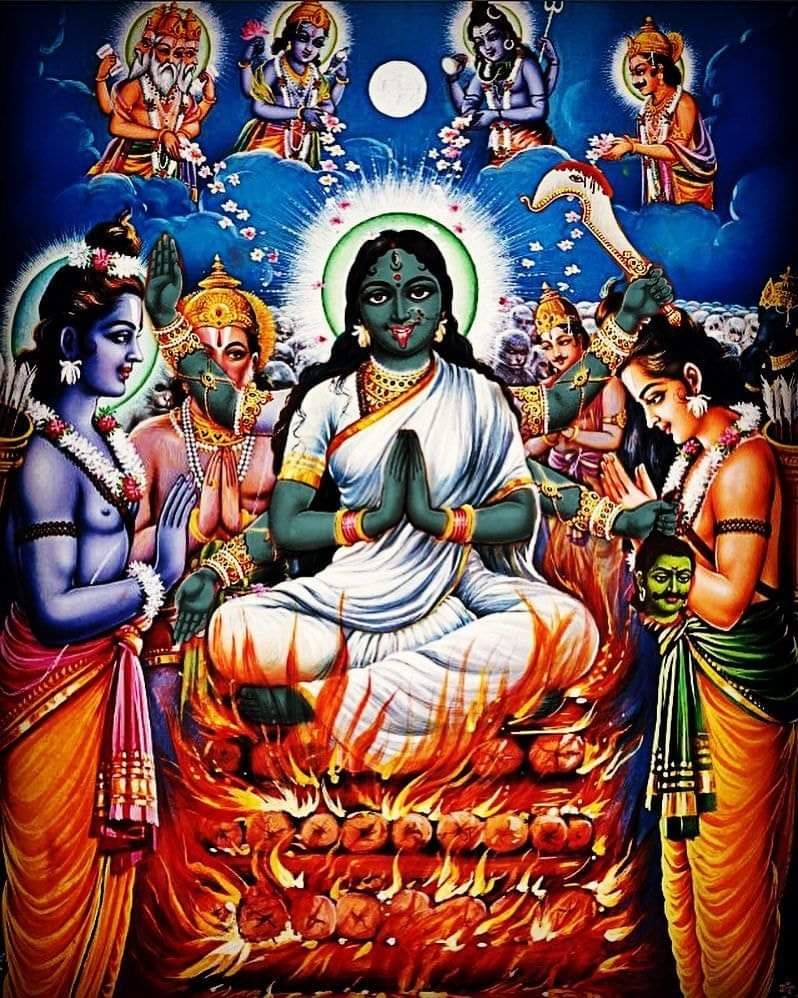

The ‘real’ Sita: At the sight of her husband, Sita transforms into the goddess Kali. Then this happens:

She destroys hundreds of demons, severs all of Ravana’s thousand heads with one stroke, and proceeds to play with the heads like balls. At that moment, a thousand “mothers” or divine female beings spring out of the pores of her body… Sita, now in the form of Kali, performs a dance of destruction that terrifies the Gods, who try to appease her with prayers but are able to do so only when they bring Rama back to life.

Much as Arjun with Krishna on the battlefield, Rama asks Sita to reveal her universal self—Parameshwari or Shakti, the divine feminine principle. And he praises her by reciting all of her 1,008 names. She returns to her human form and accompanies him back to Ayodhya—assuming her role as the good wife.

Point to note: This Sita is more likely to smile than cry—and there is no description of her abduction—which is the pivotal moment in the first Valmiki version. This is also the Sita we see most often—other than the devoted spouse by her husband’s side. For example: this Raja Ravi Varma painting:

Also: Valmiki tells the sage Bharadvaja in the end that he had not previously shared these astonishing tales “because Brahma had kept them hidden.” Interestingly, even Valmiki’s original version has Shiva promising (page 156) devas distraught over Ravana that “a woman, Sita the slayer of ogres,” will be born, “and that the gods will use her to destroy the ogres.”

Bonus version: The Odiya iteration of the same tale—Vilanka Ramayana—portrays an even weaker Rama:

When all efforts to defeat this [1000-headed] Ravana fail, it was decided that Sita’s help should be sought. Much to his discomfort, Ram asks Sita to help, and Sita steps in valiantly. She knows that this is no ordinary demon and special fights call for special moves, so she uses the five arrowed weapon of Kamdev, the panchsar of Kandarp. This unsettles the demon and the Vilanka Ravan comes to her with a begging bowl, asking for love. As he sits there bent before her, Ram beheads him.

PS: Jain versions of the Ramayana—Paumachariya—have Lakshmana slaying Ravana—and not Rama. This is because Rama is the perfect epitome of non-violence—as valourised in the Jain tradition.

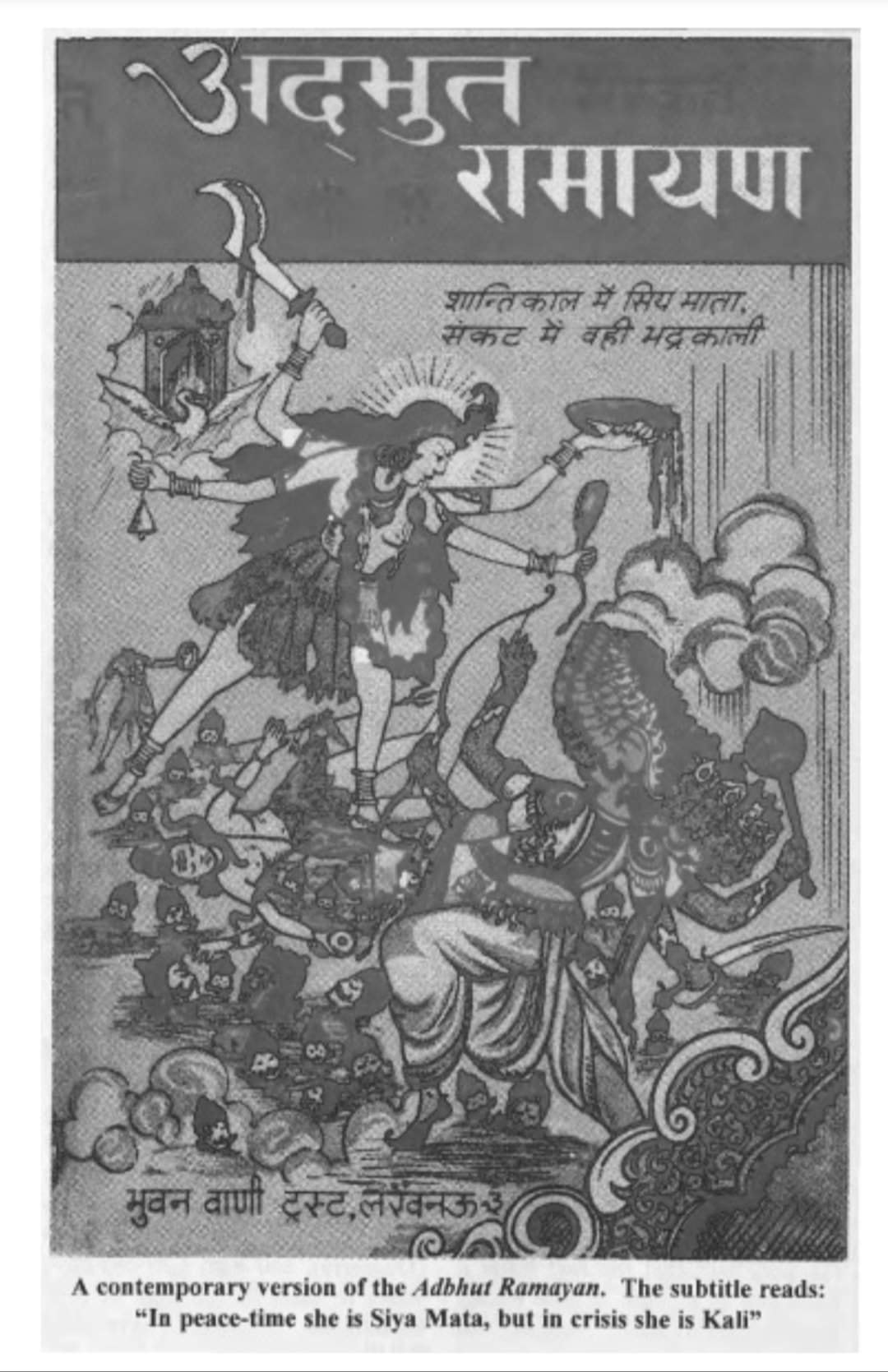

Something to see: Sadly, we couldn’t find any paintings that depict Sita slaying Ravana—other than this book cover of the Adbhut Ramayana:

And here is the cover of a Kannada version:

And another:

Beyond Valmiki: The ‘scandalous’ Sitas

The warrior Sita may be appropriate to remember on the eve of Dussehra. But there are many other Sitas—each true to a particular tradition. Some may even offend modern sensibilities.

Gondh Ramayani: In this version—which has racier variations—it is Lakshmana who goes through the agni pariksha to prove his chastity. In fact, this Ramayana is primarily about the bond between Lakshmana and Sita—with Rama playing a minor role.

In the first of seven tales, Lakshmana plays the kingri baja so beautifully that the music reaches Indralok—and the ears of Indra’s daughter Indarkamini. Instantly smitten, she arrives on earth to find Lakshmana sleeping. But he fails to awaken despite her best efforts. Enraged, she tears off her jewellery and shreds her clothes—to ‘incriminate’ Lakshmana.

The test of chastity: Soon enough, Sita comes looking for her brother-in-law—not her husband, oddly—telling her friends:

Lakshman, my darling brother-in-law is the kohl in my eyes, vermillion in the parting of my hair, he is the silken tassel hanging from my hair bun. Ram and Lakshman are like two udders of a cow, but neither my husband nor my brother in-law cares about me. Let me go myself and meet my brother in-law.

Angry at what she thinks is evidence of Lakshmana’s promiscuity, she goes to Rama—who orders him to undergo a form of agni pariksha to prove his celibacy.

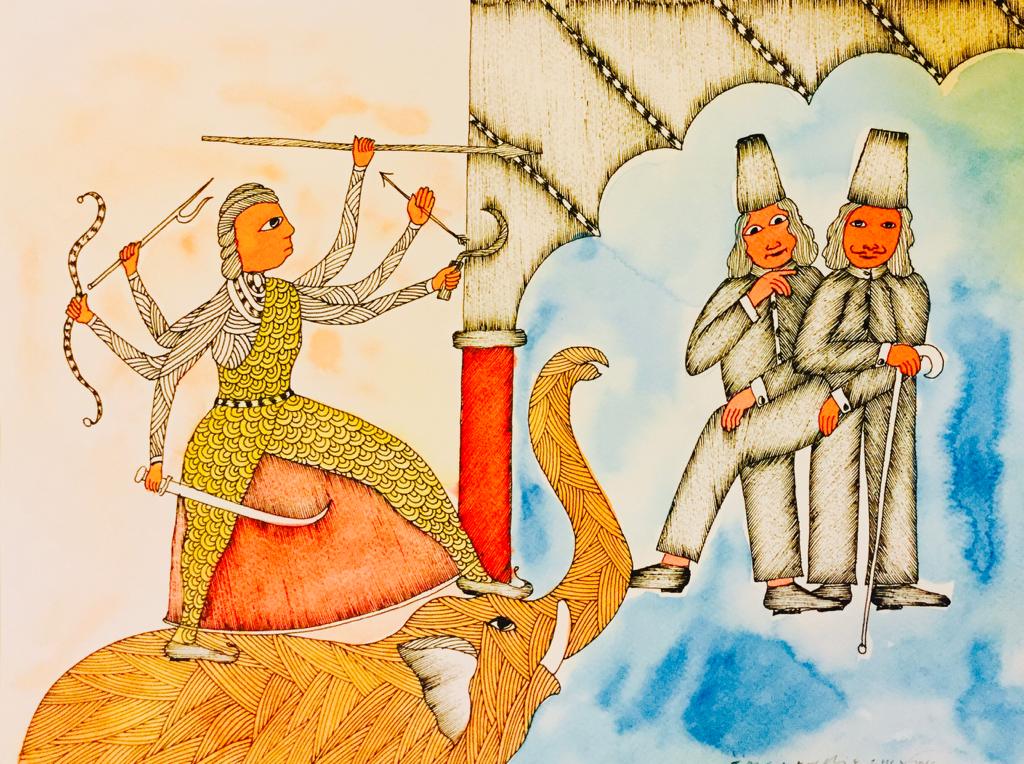

As for the rest: The rest of the seven tales in the Gond Ramayani head in an even stranger direction—when Indarkamini kidnaps Lakshmana. He has to be rescued by Rama and Sita—who battles his abductor: “Rama is deeply wounded and defeated. Sita and Indarkamini begin to fight now on the ground. They pull at each other’s hair and slap each other; blows are exchanged and abuses hurled.”

Something to see: There are very few paintings of the Gond Ramayani—except for a set of paintings done by different Gond painters for IGNCA. Below is one of them:

Point to note: In some versions, this bhabhi-devar sexual subtext is spelled out more plainly—where Sita tries to seduce Lakshmana. And as AK Ramanujam notes in his iconic essay ‘Three Hundred Ramayanas’, in Santal oral traditions, Sita is sometimes unfaithful—often seduced by Lakshmana or by Ravana.

Hazardous territory: Scholar Wendy Donniger got into serious trouble with Hindu groups for her interpretation of Valmiki’s Ramayana in her book ‘The Hindus: An Alternative History’. One of the many reasons for outrage: this bit that suggests a hidden tension between the two brothers and Sita (page 161):

The text suggests that Rama might fear that Lakshmana might replace him in bed with Sita; it keeps insisting that Lakshmana will not sleep with Sita. It doth protest too much. (Recall that when Rama kicks Sita out for the first time and bitterly challenges her to go with some other guy, he lists Lakshmana first of all.)

The reference above is to what Rama says, when refusing to take Sita back at the end of the war (page 152):

What man of good family could take back, simply because his mind was so tortured by longing for her, a woman who had lived in the house of another man? How can I take you back when you have been degraded upon the lap of Ravana? Set your heart on Lakshmana or Bharata, or on Sugriva [the king of the monkeys], or [Ravana’s brother] Vibhishana, or whoever will make you happy, Sita.

But most controversially, Donniger’s book included this bit of ‘evidence’ (Page 161):

When Rama goes off to hunt the golden deer and tells Lakshmana to guard Sita, Sita thinks she hears Rama calling (it’s a trick) and urges Lakshmana to find and help Rama. Lakshmana says Rama can take care of himself. Sita taunts Lakshmana, saying, “You want Rama to perish, Lakshmana, because of me. You’d like him to disappear; you have no affection for him. For with him gone, what could I, left alone, do to stop you doing the one thing that you came here to do? You are so cruel. Bharata has gotten you to follow Rama, as his spy. That’s what it must be. But I could never desire any man but Rama. I would not even touch another man, not even with my foot! (3.43.6-8, 20-24, 34).”

Bonus version: Then again, if you want to be truly scandalised, take a look at the Buddhist tale Dasaratha Jataka—where Rama and Sita are brother and sister in a tale of incest:

The duo is not banished but sent away to the Himalayas by king Dasaratha in order to protect them from their jealous stepmother. The stepmother is the only antagonist, for there is no Ravana in this story. When things have cooled down, Rama and Sita return to Benaras —and not Ayodhya—and get married.

The bottomline: What may be ‘feminist’ or ‘salacious’ today is but a reflection of a specific culture at a different place and time in history. Happy Dussehra!

Reading list

Ruth Vanita in Manushi has the most on the Adbhut Ramayana. Scroll has a handy list of the other Ramayanas. We included links to a number of books—which you can find online—but the authors would vastly prefer you buy them. These include ‘Gem in the Lotus’ by Abraham Eraly; ‘Professional Historians in Public’ edited by Berber Bevernage and Lutz Raphael; Wendy Donniger’s ‘The Hindus’ and AK Ramanujan’s ‘Three Hundred Ramayanas’—which was recently taken off the Delhi University syllabus. For more on the Gond Ramayani, read Mahendra Mishra and Molly Kaushal. Mint looks at the earliest feminist retelling of the Ramayana—attributed to the 16th century poet Chandrabati. Outlook offers a broader overview of the many feminist Sitas.

souk picks

souk picks