It's the trendy word deployed by wonks of all stripes—political scientists, economists, historians and more. But what does it really mean? Does it aptly describe some unprecedented epoch we’ve entered? Or is it just a fancy term for the generalised chaos that has always characterised human history? Here’s a quick guide to the debate over ‘polycrisis’.

Researched by: Rachel John & Anannya Parekh

Ok first tell me what it means?

The word is a combination of ‘poly’ and ‘crisis’—in essence, many crises. It popped up last year at a UN climate conference (but of course!). The word got an added boost when Financial Times opinion editor Jonathan Derbyshire chose it as his word to sum up 2022. ‘Polycrisis’ officially arrived in January—getting star treatment at the glitzy World Economic Forum in Davos. And it seems to have outlived its very similar sounding predecessors—e.g ‘permacrisis’, ‘multicrisis’ or ‘megathreats’. But the word wasn’t invented in 2022.

Origin story: The term has been traced back to a 1999 book authored by Edgar Morin and Anne Brigitte Kern—grandly titled ‘Homeland Earth: A Manifesto for a New Millennium:’

These authors wrote of ‘interwoven and overlapping crises’ affecting humanity and argued that the most ‘vital’ problem of the day was not any single threat but the ‘complex intersolidarity of problems, antagonisms, crises, uncontrollable processes, and the general crisis of the planet’—a phenomenon they labeled the polycrisis.

Umm, what?

Ok, let’s try this again.

An interconnected world: Michael Lawrence, Scott Janzwood and Thomas Homer-Dixon in their Cascade Institute discussion paper use the word to create a characteristic of our closely connected world:

The last few decades have made plain that global systems—from finance to security to energy—are highly susceptible to systemic risk. The dense interconnectivity of these systems enables a relatively small problem in one part of the system to spread rapidly and disable the entire system.

For example, financial systems are connected across the world. A crash in the US market affects everyone, everywhere. But these systems—economy, food, transportation etc—are also connected to each other—like so:

One example is the war in Ukraine:

Putin’s aggression, for example, has disrupted global food and energy systems, reinvigorated the NATO alliance, exacerbated domestic ideological cleavages in many countries, and threatens to divert international resources from climate action. What may appear to be separate crises in different global systems in fact interact, exacerbate, and reshape one another to form a conjoined “polycrisis” that must be understood and addressed as a whole.

Defining a ‘polycrisis’: A polycrisis is not simply a sum of individual crises that occur at the same time:

A global polycrisis occurs when crises in multiple global systems become causally entangled in ways that significantly degrade humanity’s prospects. These interacting crises produce harms greater than the sum of those the crises would produce in isolation, were their host systems not so deeply interconnected.

Or as historian Adam Tooze puts it far more simply:

A problem becomes a crisis when it challenges our ability to cope and thus threatens our identity. In the polycrisis the shocks are disparate, but they interact so that the whole is even more overwhelming than the sum of the parts. At times one feels as if one is losing one’s sense of reality.

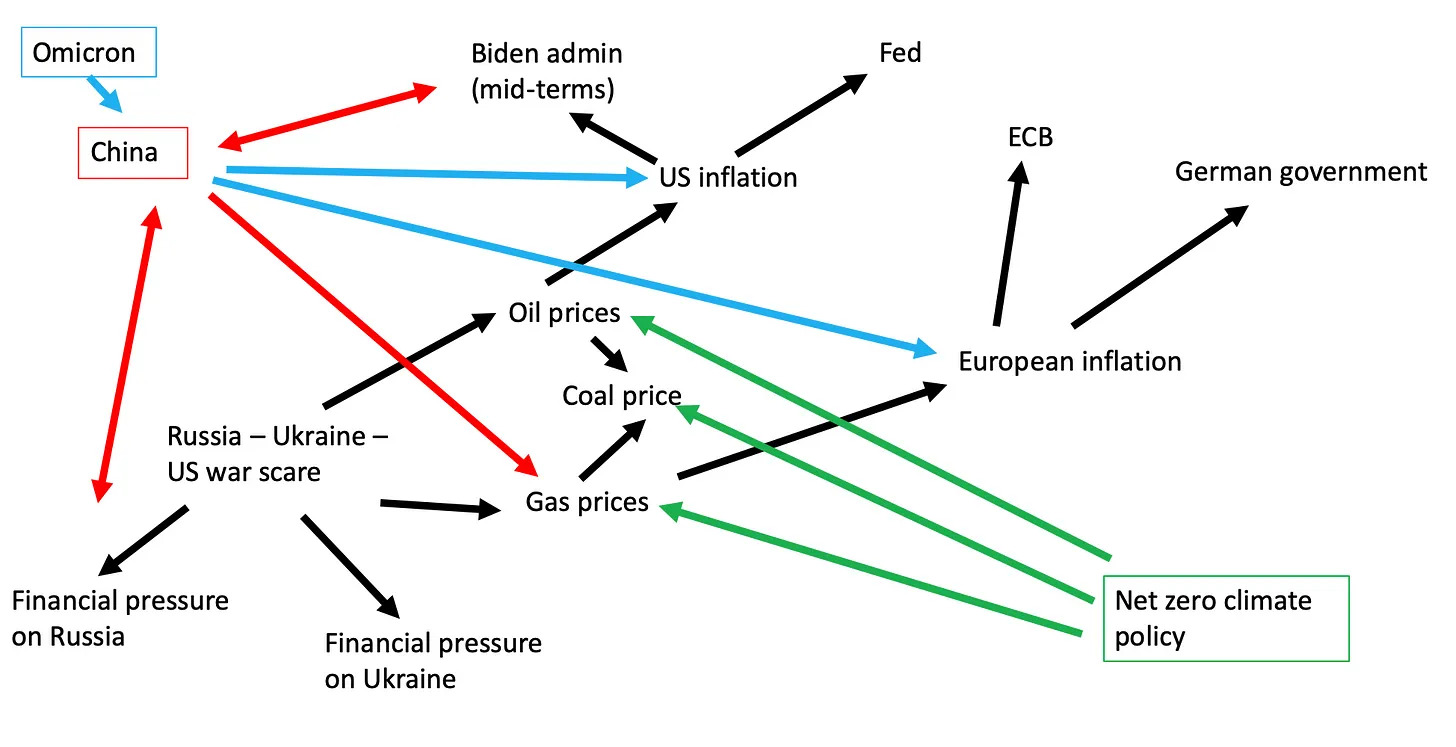

Here’s Tooze’s chart of the world before the Ukraine invasion:

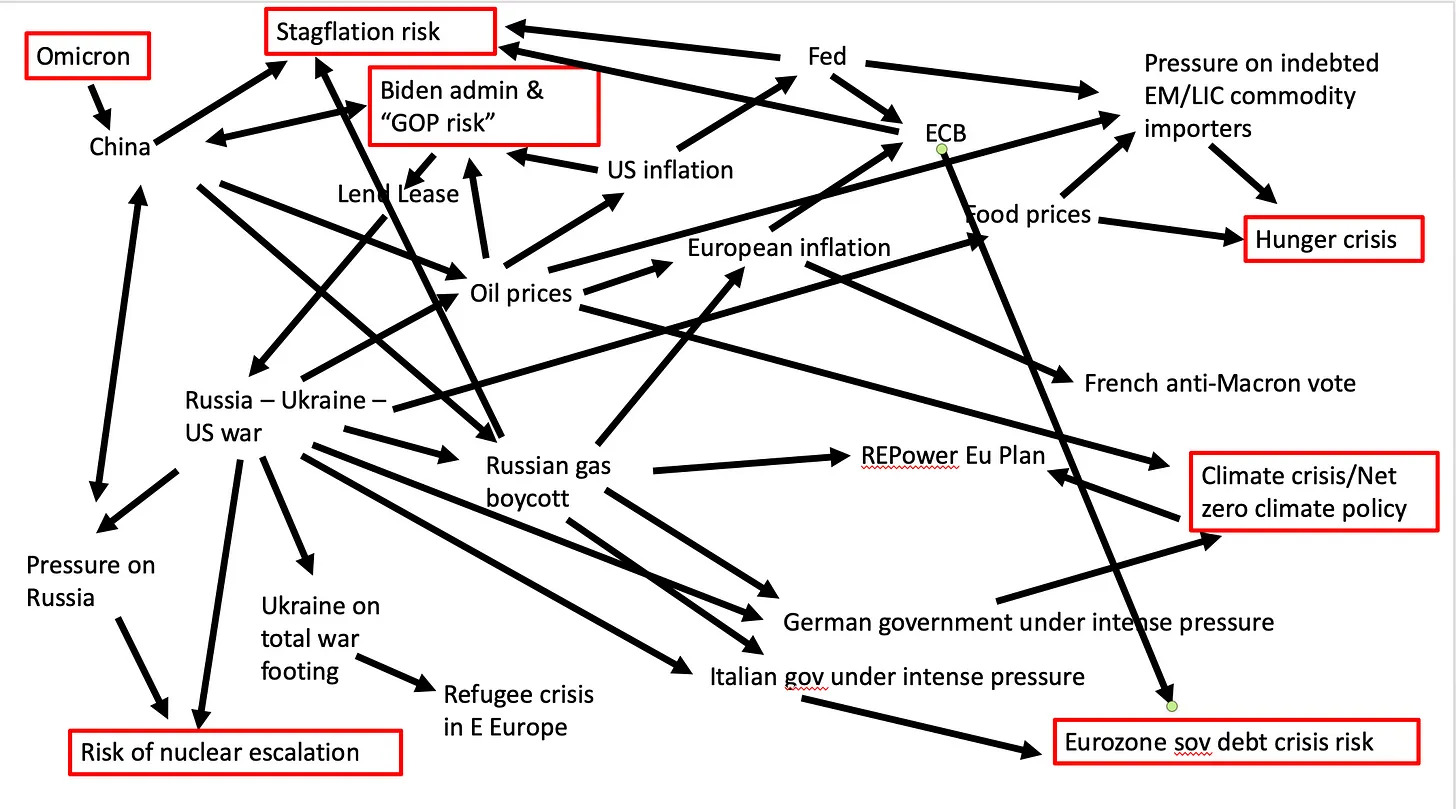

Here’s what happened to his chart after the invasion:

And this polycrisis is a new thing?

Well that’s up for debate. Some view it as a “research concept”—that we can apply to understand situations in the past and present. Others say the word captures the unique and unprecedented era that we have entered.

Polycrisis as concept: A number of experts say we’ve always lived through polycrises—we just didn’t know it until now. Here’s an example from Nitin Pai:

Most people are familiar with the birth of Bangladesh following a war between India and Pakistan in 1971. But a closer examination of the period shows that this was not only a consequence of an ethnic divide between Pakistan’s two wings, but of a natural disaster (Cyclone Bhola), an ideological crisis within international Communism, a geopolitical crisis between Cold War blocs, persistent economic crises in the subcontinent, a genocide and a humanitarian crisis concerning millions of refugees.

Pai argues that past theorists who attributed the state of the world to a singular cause—capitalism, inequality etc—were just plain wrong. We’ve now realised that causality is far more complex:

[L]ike the blind men and the elephant, this only means that back in the 1970s and 80s, analysts were too preoccupied with the parts they were concerned about and didn’t know or didn’t care enough about the interconnections… If people blamed “late stage capitalism" in the past, it was not because there was no polycrisis then; only that the causes were incompletely identified.

Or is it ‘the’ polycrisis? Political scientists like Thomas Homer-Dixon argue that polycrisis describes where we are right now:

There is only one polycrisis: this historical epoch, when humanity has created a world interconnected and interdependent to an unprecedented degree, combining vast material wealth with radical inequality and teetering on the threshold of ecological collapse. It is a truly novel phase of history, different from anything in the track record of our species.

The four markers: Homer-Dixon lists four signs that prove that our situation as novel and unprecedented:

- Humans consume unparalleled amounts of energy: “Driven largely by soaring use of cheap fossil fuels, our energy consumption has increased sixfold since 1950.”

- The energy balance of the planet has reversed itself. The amount of energy arriving on Earth from the sun is no longer equal to the amount reflected back by Earth. The reason: greenhouse emissions. The result: global warming.

- There are an unprecedented number of humans: Since 1925, the world’s population has quadrupled to 8 billion—with a total mass of just under 400 million metric tons.

- And we are all connected as never before—by planes, ships, pipelines and above all, the internet: “Billions of us around the world now carry in our pockets a computer that would have filled 50 Pentagons in the mid-1950s.”

A fragile cornfield: So there are lots of humans who are very similar and very interconnected—which means things get very ugly, very fast. Homer-Dixon compares us to a field planted with rows of genetically identical corn. A disease can easily jump from one plant to another—and because they’re homogenous, it will be equally harmful to all. To put it in human terms:

The human population is now just like that field of corn. We’re a highly connected, largely genetically identical biomass, except in this case, we’re vastly more massive and our “field” extends across much of the planet’s surface. And, sure enough, we’re exhibiting a monocrop’s vulnerability to pathogens, so we’re using (and in some cases overusing) antibiotics and antivirals just the way we use pesticides on our crops.

Yikes, that’s dreadful… isn’t it?

Well, it depends on how you view the polycrisis. Some think it’s a made-up term. Others say it offers hope for more effective solutions.

Just more mumbo jumbo: Right-leaning historian Niall Ferguson dismissed it as a pointless word that doesn’t describe anything new—the polycrisis is “just history happening.” Gideon Rachman in the Financial Times calls it one of his “least favorite cliches”—“does it actually mean anything? Other than—there's lots of bad stuff happening simultaneously and one thing can affect another.” ‘Polycrisis’ also makes many liberals unhappy—who see it as a way to cover up the role of “predatory globalised capitalism” in creating these crises.

Noah Smith offers a more sympathetic critique:

This is not to say the world is free of crises and risks; there are plenty out there. Nor is it to say that our current era has less than others; this is very hard to judge. But the idea that these crises are all related may be a case of apophenia — our natural human tendency to perceive connections that don’t actually exist, or are far weaker than we think.

Necessary understanding, new hope: Its advocates see it as necessary to change our mindset—which is wired to solely focus on our most immediate problem:

Focusing on the acute crises and waiting for the normal times to return, in order to handle the creeping crises, is simply a recipe for disaster. To quote Laurie Leybourn of the think-tank IPPR speaking to The Guardian in February: ‘We absolutely can drive towards a more sustainable, more equitable world. But our ability to navigate through the shocks while staying focused on steering out the storm is key.’

And if things are indeed interconnected, we can also create a “virtuous cascade” of good decisions.

FYI: Even a sceptical Smith is a believer in the “polysolution:”

I look out in the world and I don’t see a polycrisis; I see an emerging polysolution. The looming threats of climate change and authoritarian revanchism, combined with the shocks of Covid and inflation, have stirred both policymakers and businesses to action. And many of those actions will end up addressing multiple crises rather than just one… External shocks can bring the entire system crashing down, but they can also spur humans to get serious and start working together.

The bottomline: We tend to agree with Bloomberg columnist Andrea Kluth, who sums it up brilliantly:

So what’s new is not that humanity suddenly has uncountable problems that are all linked — that’s always been true — but that it’s finally dawning on us how little we understand about the mess we’re in. And we hate, hate, hate that feeling. This apocalyptic angst — we don’t comprehend what’s going on but it’ll end badly — is what the highfalutin word polycrisis expresses.

My practical advice is to stop coining Greek neologisms and attack complexity with simple words. We have problems, emergencies and catastrophes, but we also have solutions — from mRNA vaccines to, who knows, maybe fusion energy one day. I suggest… the rest of us, just pick whichever crisis they know something about, and get back to work solving it.

Reading list

For the most detailed version of the polycrisis theory, read this paper by Michael Lawrence, Scott Janzwood and Thomas Homer Dixon. There’s a shorter version in Vox. Ville Lähde’s essay in Aeon parses the difference between polycrisis as a concept—and as a historical epoch. For the sceptics, read Andrea Kluth and Noah Smith. We found this Mint column by Nitin Pai very useful—especially for looking at applications to India. If you want to look up Adam Tooze, check out his newsletter Chartbook.

souk picks

souk picks