Last week, we hosted a lavish Onam meal in Mumbai. The stories of Kerala—narrated by historian Manu Pillai—were every bit as fabulous as the food. The true stories of the South challenge not just how we imagine Kerala—but also the history of India.

Editor’s note: The inaugural event of our True South series of immersive dinners was a wild success—and sold out in less than two days. Sadly, we can’t give you the taste of the amazing Onam feast. But we offer this retelling of little-known but important stories—which recapture some of the experience.

First, a quick intro to True South

On August 29—to mark Onam—we hosted a fabulous dinner at The Bombay Canteen called ‘Raja Ravi Varma’s Feast of Wonders’. Our guest historian Manu Pillai uncovered the hidden histories of the state—while the lavish feast reminded guests that there is far more to Onam cuisine than just sadhya. (You can read lots more about the dinner over at Mint Lounge, The Hindu and Forbes)

This was the inaugural event of the True South project—a collaboration between splainer, enthucutlet (our content partner and sibling of The Bombay Canteen) and Chef Manu Chandra. In what may be a global first—and certainly a first in India—we weaved together historical storytelling, fine cuisine and AI art to create a unique kind of experiential dining.

The aim of True South: is to offer the untold and immensely diverse history, identity and culture of the five states—buried underneath the many cliches about ‘Naatu Naatu’, Kanjeevaram sarees, tech hubs or dosais. But the name also has a deeper meaning. Where ‘true north’ represents our life’s purpose, ‘true south’ signifies our rootedness. Who we are and who we are becoming is shaped by who we were—or rather, the narratives we tell ourselves about our past. As you will see below, stories of Kerala are also stories of India and our relationship with the world.

Also: We have a very pretty logo:)

Story #1: An Atlantis for Brahmins

The background: The hero of Kerala’s best-known origin story is one of Vishnu’s avatars: Parasurama. According to the state’s high-caste Brahmins—the Namboodiris— the state was bestowed upon them by this immortal incarnation. A creation myth that legitimised their immense privilege:

[T]he Namboodiris “occupied the highest position among all other communities…collected fabulous amounts as rent, enjoyed undisputed supremacy over the tillers of the soil, and maintained intimacy with the ruling monarchs”. The immortal Parasurama, they claimed, had bestowed Kerala upon them, this being the fount of their legitimacy. Every other group was to serve, the Namboodiris apportioning caste status and privilege to those who subscribed to this world view.

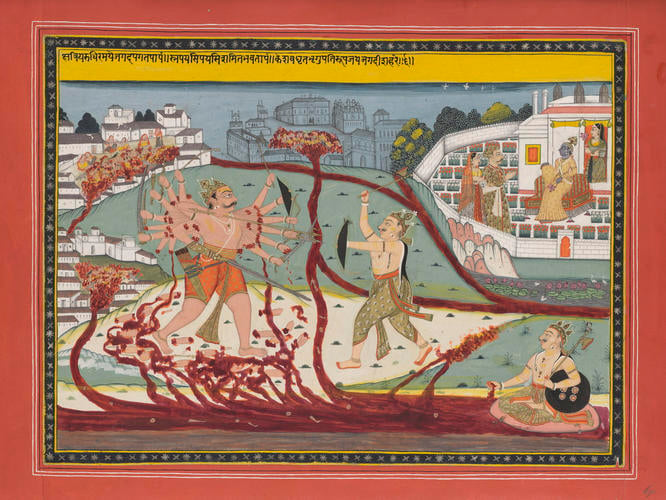

Kerala rising: According to the myth, Parasurama was the son of Renuka and the sage Jamadagni—who owned a bountiful cow. The Kshatriya king Kartavirya Arjuna coveted the cow—and beheaded Jamadagni in his attempt to possess it. Enraged by the murder of his father, Parasurama killed 21 generations of kshatriyas—including of course the thousand-armed king—as you can see in this 13th century illustration from the ‘Gita Govinda’:

His blood-lust slaked, Parasurama sought to atone for his sins—and is told to do so by gifting land to Brahmins. So he threw his bloody axe into the sea—and the land from Gokarna in Karnataka to Kanyakumari in Tamil Nadu rose from the waters—henceforth bestowed for eternity to 64 Brahmin families. As one British historian describes it:

To people this land, Parasurama is said to have first brought a poor Brahman from the shores of the Krishna River. This man had eight sons and the eldest was made the head of all Brahmans from Kerala. Other Brahmans are next brought and located in sixty-four gramas or villages. Ships with seeds of plants and animals next came, also came eighteen samantas (sons of Brahmins and Kshatriya women), Vaisya and Sudras.

PS: There’s a much nastier version of this myth: Parasurama beheads his own mother on the orders of his father—who is enraged by her infidelity with Kartavirya.

The evolution of Parasurama: The sixth Vishnu avatar has become highly popular—and far more macho. This is what he looked like in an 18th century painting:

And here is Parasurama in this 1825 miniature—likely made for an Englishman:

But by the early twentieth century, Indians were eager to assert their masculinity—to counter colonial stereotypes of the effeminate native. By the time Raja Ravi Varma paints his Parasurama in 1910, he has turned into the muscular, bearded yogi we now know:

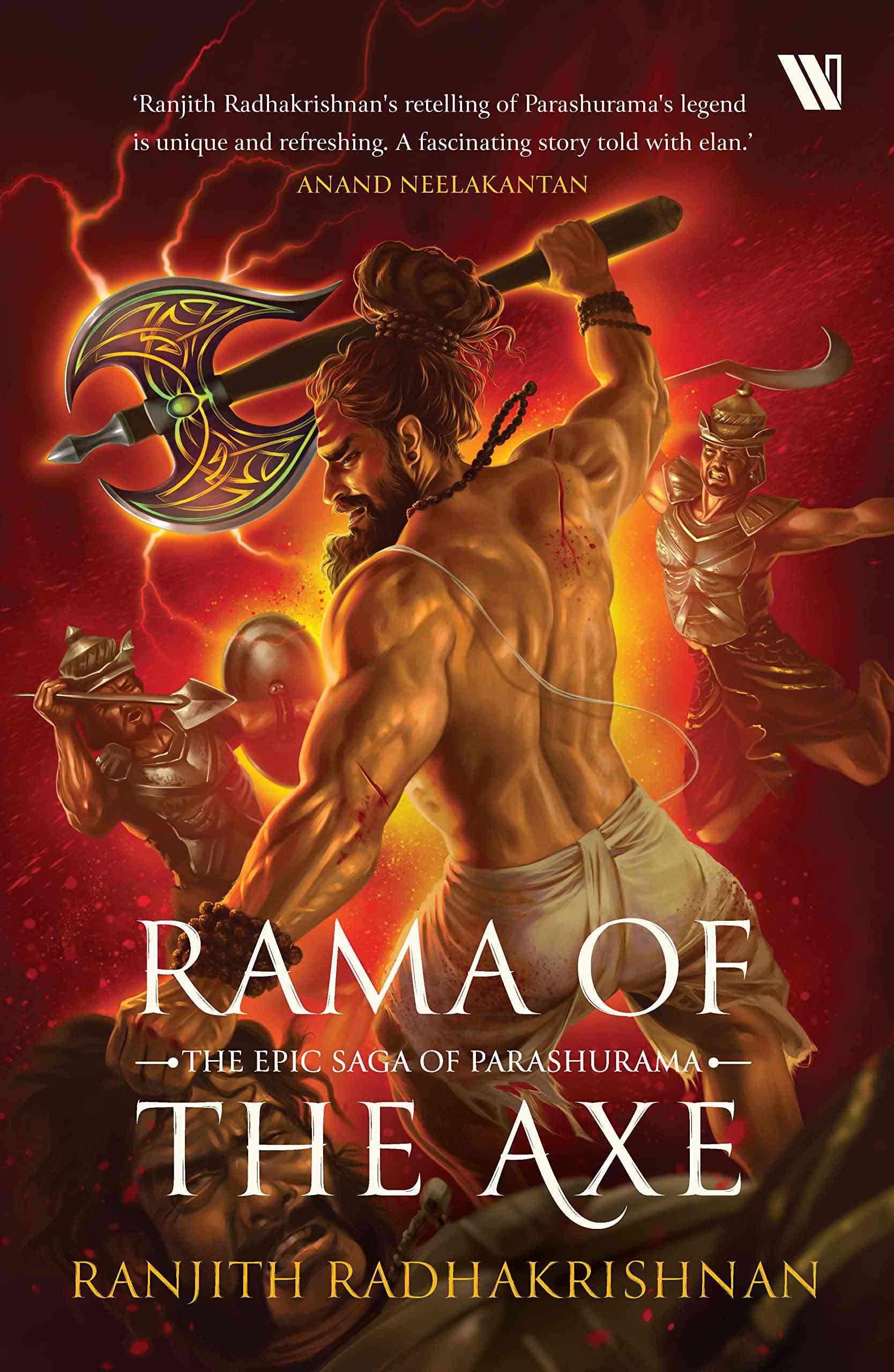

The trend has accelerated even further in recent years with the rise of Hindu nationalism. Parasurama in pop culture today more resembles a Marvel superhero than a god. Thor, anyone?

Irony alert: Parasurama seems to have receded in the popular imagination of Malayalis themselves. But he has found new life as the creator of Goa—though in its version, the land was unsurfaced by an arrow not an axe.

Something to see: This vid—created by artist Ari Jayaprakash—captures the imagery of the myth using AI-generated art:

Speaking of transformations: As you may know, Onam is linked to Vamana’s victory over Mahabali—who was a greatly beloved tribal king, so much so that gods became envious and afraid. Hence, Vishnu appeared as a Brahmin dwarf and asked for three paces of land from the king. Vamana covered the heavens and the mortal world in two steps—leaving the king no choice but to offer his own head for the third. Consigned to the netherworld, Mahabali is allowed back on earth for one day on Onam—and is welcomed back by rejoicing Malayalis.

Now, this is an early eighteenth century miniature of the myth:

Here is how Raja Ravi Varma painted this myth back in 1910:

That heroic royal figure has since disappeared. Mahabali today is a “rotund, moustachioed, garishly dressed and bejewelled” Asura king—a development that surely will make those jealous gods happy:

Mercifully, Malayalis have fiercely resisted all efforts to recast Onam as Vamana Jayanti.

Story #2: The splitting of the moon

The background: This is the origin story of the royal kingdoms of Kerala—including those of Cochin and Travancore. They trace their origins to a Chera king who may or may not have existed. It is recorded in a number of texts—including the Brahmin text, the Keralolpathi.

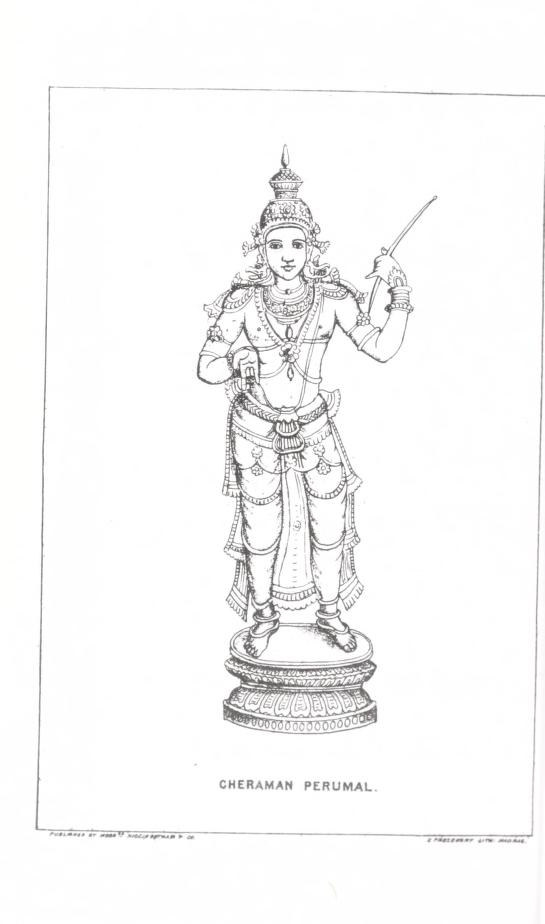

The miracle of the moon: According to the myth, all of Kerala was ruled by one king: Cheraman Perumal—who was the last of the Chera dynasty. This one of the few depictions of the king:

One night, when the king was on his balcony, he witnessed an astonishing sight—the moon splitting into two—and merging again. The king consulted his advisers and astrologers, but none could explain this miracle. Then a group of Arab traders told him that it was none other than their Prophet Muhammad who had split the moon in two.

The journey to Mecca: Cheraman Perumal was so impressed with their stories of the Prophet that he journeyed to Mecca to meet him. Before doing so, he divided all his land among the chiefs—who later became the royal families of Kerala. According to the myth, Perumal converted to Islam—and died in Arabia.

The oldest mosque in India? According to the legend, one of Perumal’s friends later returned to Kerala and built the Cheraman Juma Masjid—which is believed to date back to 629 AD, established in the lifetime of the Prophet:

A different story of Islam: Whether the myth is true or not, there are clear traces of Islam in Kerala that predate the ferocious raids of Mahmud of Ghazni on North India in the early 11th century. As Pillai writes:

There are, of course, quibbles about how far the legend is accurate, but claims of its antiquity may not altogether be overstated. While we don’t know if Islam reached Kerala precisely in the early seventh century, just over 200 years later there was certainly a Muslim community there prominent enough to witness and sign in Arabic a royal grant by a Hindu king to a Christian merchant. In other words, when Sthanu Ravi Varma Kulasekhara issued orders in favour of Mar Sapir Iso (who also built a church in Kollam) in the mid-800s, among those present were Maymun, son of Ibrahim, and Bakr, son of Mansur.

While the dates may vary, it is almost certain that the masjids in Kerala predate the earliest mosques in North India built by Qutb-ud-Din Aibak—Muhammad Ghori’s viceroy who became the sultan of Delhi. He began construction of Quwwat-ul-Islam Mosque in 1193 AD on the remnants of 27 temples destroyed by him. The history of Islam in the North is rooted in conquest, destruction and loss—unlike the South:

There is, however, something to be learnt from the tale of Cheraman Perumal and the masjid bearing the name of this Hindu king on India’s west coast. Perhaps it was because Kerala was traditionally a trading society that the “foreign” did not always seem alien—that there was always room for the new, for the unfamiliar, and for the different to be welcomed and made one’s own. While elsewhere there may be other stories, and lasting memories of loss and pain, deprivation and violence, perhaps we can try and look ahead. Like Cheraman Perumal, who saw an idea he liked and set sail to discover it, we too can seek inspiration from other, calmer terrains.

Something to see: Here’s one of the AI art vids that prettily reimagines the legend of Cheraman Perumal:

As for those Christians: The story of how Christianity came to India dates back to St Thomas—one of 12 apostles of Jesus. Known as ‘Doubting Thomas’ for being sceptical about the resurrection of Christ, he is supposed to have landed in South India around 52 AD. One myth claims that he converted high-caste Brahmins to Christianity by performing miracles—a tale claimed proudly by Saint Thomas Christians aka Syrian Christians or Nasrani Mappila. Another legend recounts Thomas’ spirited debate with the local goddess Bhagvati in Pallippuram:

They commenced a discussion on their respective faiths, till, many hours having passed, the goddess grew weary, and decided to return to her sanctum in Kodungallur. “St Thomas,” Francis Day tells, “not to be outdone, rapidly gave chase, and just as Bhagavathy got inside the door post, prevented its closing.” As Susan Bayly, the anthropologist, explains, both Bhagavathy and St Thomas are perceived as equally divine in this story, their chase tinged with a hint of romance. And while the Apostle did not gain access to Bhagavathy’s shrine and followers, he secured a “significant foothold” in the region.

Also this: In yet other iterations, Bhagvati is the elder sister of the Virgin Mary—who is taken out to see her sibling once a year, as this temple priest explains:

Mary is another form of the Devi. They have equal power. At our annual festival the priests take the goddess around the village on top of an elephant to receive sacrifices from the people. She visits all the places, and one stop is the church. There she sees her sister.

Point to remember: At this time, there were no Christians in Europe—which was ruled by Claudius—the successor to Caligula and predecessor of none other than Nero. European Christians didn’t arrive in Kerala until Vasco Da Gama came ashore in 1498 to meet the Zamorin of Calicut—and made a bit of an ass of himself:

Da Gama and his men received one courtesy audience from the Zamorin and they were greatly impressed by the assured opulence of his court. But when they requested an official business discussion, they were informed of the local custom of furnishing presents to the ruler first. Da Gama confidently produced “twelve pieces of striped cloth, four scarlet hoods, six hats, four strings of coral, a case of six wash-hand basins, a case of sugar, two casks of oil, and two of honey” for submission, only to be jeered into shame. For Manavikrama’s men burst out laughing, pointing out that even the poorest Arab merchants knew that nothing less than pure gold was admissible at court.

Of course, nineteenth century Portuguese artist Veloso Salgado, paints quite a different picture below—for such is the nature of colonial memory:

The bottomline: As we said in the beginning, who we are and who we are becoming is shaped by the stories we tell ourselves about our past. As Indians, we have the good fortune to have many stories to choose from.

souk picks

souk picks