Bazaar paintings: Where East met West

Editor’s note: This is a guide to Bazaar Paintings. These guides are brought to you by our partner, MAP Academy, a wonderful online platform aimed at building knowledge of South Asian art. Each month, we will carry an essay from their Encyclopedia of Art—a fabulous resource for anyone who wants to learn about our shared history and culture. The MAP Academy is a non-profit online educational platform committed to building equitable resources for the study of art histories from South Asia. This article originally appeared on the MAP Academy website, with due image credits for photos used in this republished piece.

About the lead image: It is titled ‘A Man on a Sedan Chair’ from Patna, Bihar, India, c. 1825. Details: Opaque watercolour on paper, 22.54 x 27.78 cm. Image courtesy: Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

—

A type of early modern art from India, bazaar paintings emerged as a hybrid form of commercial art. They were created in large numbers for European expatriates and visitors to India, as well as for local urban consumers. Bazaar paintings are characterised by a combination of features and conventions of the Western Academic style with Indian miniature painting or other local traditions, and depict a range of religious and secular subjects. The two most recognised categories of bazaar paintings are Company School and Kalighat painting, which differ considerably in their style, treatment and subject matter.

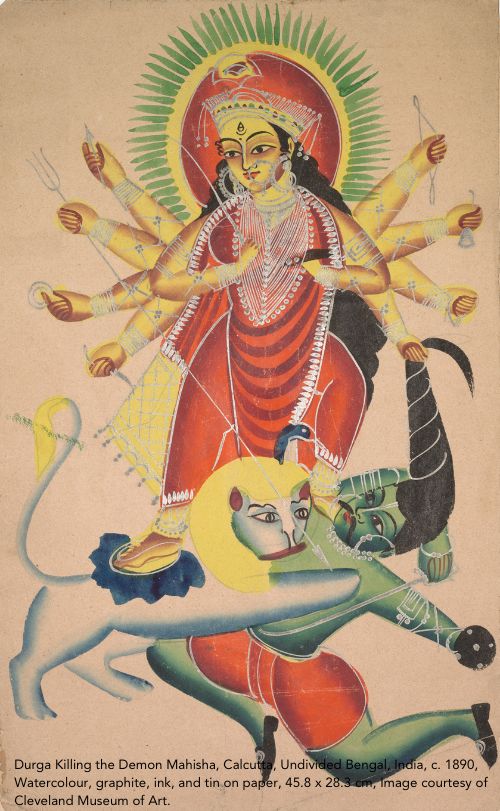

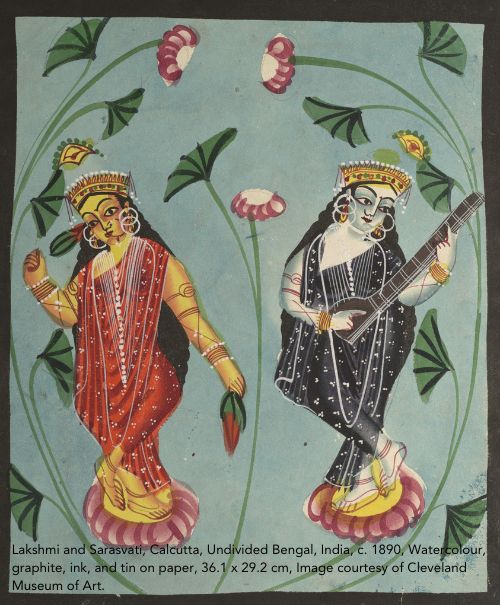

Company paintings served as a visual record of colonial territories through depictions of monuments, landscapes, flora and fauna, people and their occupations, and social and cultural activities. On the other hand, Kalighat paintings typically acted as both religious souvenirs and social commentaries. Patna and Calcutta (now Kolkata) were important centres for this market-driven art in the nineteenth century. The practice also took root in other existing centres of traditional art, such as Madras (now Chennai), Mysore (now Mysuru), and the Maratha court of Tanjore (now Thanjavur).

The Persian word bazaar translates to “market.” During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, as global exchanges with India expanded, bazaars became spaces that connected European traders with Indian consumers, creditors and producers. Through this period, bazaars were impacted by a series of consequential changes that impacted the production and consumption of art objects. These were the growth of the British East India Company, an increasing presence of European employees of the Company throughout India, and an influx of European pictures and techniques, including mass reproduction technologies such as lithography. These factors combined to create a new class of patrons and methods for Indian artists, at the same time that patronage from Indian courts was declining.

The Persian word bazaar translates to “market.” During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, as global exchanges with India expanded, bazaars became spaces that connected European traders with Indian consumers, creditors and producers. Through this period, bazaars were impacted by a series of consequential changes that impacted the production and consumption of art objects. These were the growth of the British East India Company, an increasing presence of European employees of the Company throughout India, and an influx of European pictures and techniques, including mass reproduction technologies such as lithography. These factors combined to create a new class of patrons and methods for Indian artists, at the same time that patronage from Indian courts was declining.

Indian artists thus began to adopt European styles and aesthetics, catering to the tastes and appetites of their new clientele. The resulting hybrid style, called the Company School, is characterised by the use of watercolour, linear perspective, and shading. Early works within this genre were dependent on individual commissions.

However, the growing demand in the local and tourist market and the increasing familiarity of artists with Western modes of representation led several of them to operate their own workshops. Successful artists often sold their works directly, or through established bazaars and trade networks. Particularly popular were sets of paintings depicting fairs and marketplaces, as well as local costumes and traditional occupations. Known as firka sets, these were often sold as tourist mementos.

Another category of bazaar paintings is Kalighat painting. These paintings were also sold as tourist and pilgrimage souvenirs, but usually from the alleyways in the Kalighat area and from other temples in Calcutta, rather than from workshops run by professional artists with courtly pedigrees. The paintings, originally executed as palm-leaf scrolls, were later produced on inexpensive paper with the addition of distinctively European characteristics such as watercolours, shading for volume, and three-quarters profiles.

Although generally linked to Hindu temples, the visual repertoire of Kalighat paintings included themes from other religions, such as Islam, as well as secular subjects. These included interpretive depictions of current events, Bengali proverbs, vignettes from contemporary literature and popular fiction, and satirical visual commentaries on the cosmopolitan culture and lifestyles of the emerging middle and upper classes of the city.

The commercial success of these forms of painting, followed by a rise in the popularity of similarly themed prints, resulted in indigenous presses emerging in these and other colonial centres. Bazaar paintings began to decline towards the late nineteenth century following the advent of photography in India, which superseded painting as both a commercial and colonial asset.

The MAP of Knowledge

The MAP Academy encourages knowledge building and engagement with the visual arts of South Asia through its free and fully accessible offerings—Encyclopedia of Art, Online Courses, and Stories. If you liked this story, you might be interested in Textiles from the Indian Subcontinent—a first-of-its-kind online short course developed by the MAP Academy exploring the histories of South Asian textiles. It provides insights into the processes of cloth production and aims to create awareness and appreciation of age-old textile traditions, examining their global impact on culture, fashion, and sustainability. This course is free, self-paced and offers learners a Certificate of Completion. To explore new and interesting stories from South Asia’s art histories, follow us on Instagram.

souk picks

souk picks