This year we will bid farewell to La Niña and say hello to her terrible twin El Niño. Many experts are worried that the so-called Little Boy could offer us a preview of life in global warming hell. And in India, that may mean a failed or weak monsoon.

Researched by: Rachel John & Priyanka Gulati

Umm, I don’t really know what El Niño is…

Think of the Pacific Ocean as a bathtub—whose top layer (200 metres) is filled with warm water. The ocean underneath is very cold—and there is a sharp difference in temperature between the two.

When things are ‘neutral’: Trade winds blow from east to west over the tropical part of the Pacific Ocean—from South America toward eastern Australia. They push all that surface warm water against the coastline of Australia. The water level there can be one metre higher than on the South American coast—where cold water rises to the top in a process called ‘upwelling’. This ‘neutral’ pattern generally brings rain to Australia and SE Asia.

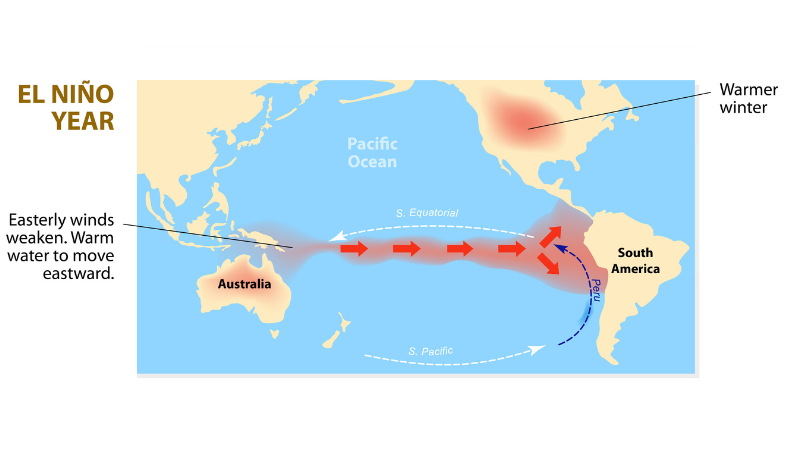

An El Niño year: This is what we get when those east-to-west trade winds are weak. Then all that warm water flows back toward the Americas—taking some of the rain with it.

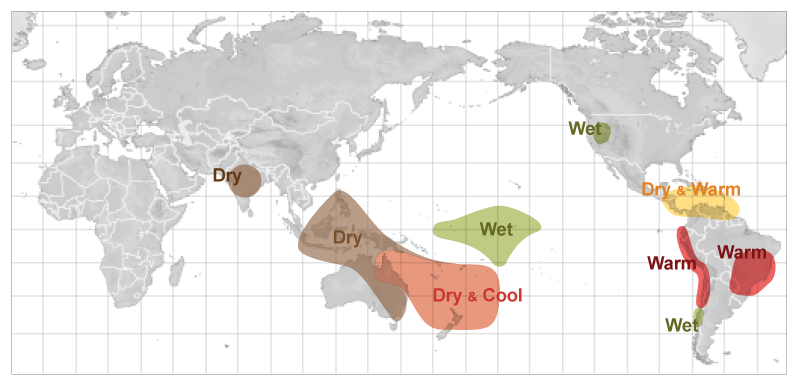

The change in the trade winds also changes the direction of the jet stream—which is a band of strong wind that blows from west to east all across the globe. During El Niño years, the jet stream tends to shift south. And that has a knock-on effect on weather all around the world. Here’s what an El Niño year typically looks like between December and February:

And here is what it looks like between June and August:

And here is what it looks like between June and August:

A La Niña year: This is when the east-to-west trade winds are stronger than usual. This pushes even more warm water toward Australia/Asia—bringing higher than normal rainfall. The jet stream moves northward—which changes the weather pattern around the world. This is what La Niña weather looks like December through February:

And here’s the state of the world between June and August:

The yo-yo pattern: between the two is known as the El Niño-Southern Oscillation cycle. La Niña is not included in the name because the phenomenon was discovered much later by scientists. The term El Niño (the warm phase) was first noted by Peruvian fishermen in the 19th century—who noticed that coastal waters would get warm around Christmas time. Hence, they called it El Niño, meaning “boy child”, after Jesus.

The yo-yo pattern: between the two is known as the El Niño-Southern Oscillation cycle. La Niña is not included in the name because the phenomenon was discovered much later by scientists. The term El Niño (the warm phase) was first noted by Peruvian fishermen in the 19th century—who noticed that coastal waters would get warm around Christmas time. Hence, they called it El Niño, meaning “boy child”, after Jesus.

Key point to note: These El Niño or La Niña phases typically last nine to 12 months. But this time La Niña decided to hang around for the third consecutive year—marking the first “triple-dip“ of the 21st century. According to meteorological experts:

It is exceptional to have three consecutive years with a La Niña event. Its cooling influence is temporarily slowing the rise in global temperatures – but it will not halt or reverse the long-term warming trend.

So now we’re going to fry with El Niño?

Wait, let’s look at the bright side first.

One: Very little is predictable in climate science. El Niño/La Niña rarely follow a proper schedule. Experts are confident that La Niña’s days are numbered—but are still not sure when the dreaded Little Boy will show up. According to the World Meteorological Association, the odds gradually rise from 15% between April and June—to 35% from May to July—and max out at 55% between June and August. But it’s far too early to tell: “In autumn, the Pacific Ocean can sit in a state ready for an El Niño to occur, but there is no guarantee it will kick it off that year, or even the next.”

Two: Yeah, El Niño typically brings hotter and drier weather. And yes, La Niña tends to put a brake on the average surface temperatures—preventing a record-setting warm year. But neither follows a predictable pattern. The effects of El Niño will also depend on how strong it is—measured by how much warmer the high sea-surface temperatures are compared to the normal. Climate change is supposed to give us more of these Super El Niños. But other experts claim global warming has resulted in unexpected variations such as El Niño Modokis. In other words, no one knows what to expect.

That wasn’t much comfort, but out with the bad news…

Let’s start with this dismal fact: researchers say that there is an 89% chance that we will experience a ‘Super El Niño’. And it is going to make the planet feel hotter than ever. As The Hindu notes: “An El Niño year creates a global-warming crisis in miniature, since the warm water spreading across the tropical Pacific releases a large amount of heat into the atmosphere.”

Breaking the 1.5°C threshold: The big problem is that the planet is already heating up at an accelerating rate due to human activity. Global temperatures increase by about 0.2°C on an average during an El Niño episode, and fall about 0.2°C during La Niña. The latter hasn’t happened—and even a 0.2°C increase would tip us over into a full blown crisis.

The Super El Niño that kicked into gear in 2016 gave us the warmest year ever recorded. Many experts, therefore, worry that the global temperature will warm by more than 1.5°C for the very first time in 2024. That’s when very bad things start to happen. And La Niña’s record offers little comfort:

To me, the big story is really that we have had so high temperatures in the last three years while we had La Niña. How much extra will come if we have a strong El Niño later this year? That is, of course, also interesting, but the amazing thing is that we have had these very high temperatures globally over the last three years.

The silver lining: Any breach of the 1.5°C threshold would be temporary—and survivable. And we’ll likely cool back down thanks to the next La Niña phase.

El Niño’s reign of terror: We already know what a super El Niño can do. Here’s what happened in the past:

- In 1992, Africa witnessed the worst drought in a century because of El Niño, affecting around 72% of the population.

- In 2015, the Great Barrier Reef in Australia saw the most devastating coral bleaching event due to marine heatwaves.

- Drought and fires killed roughly 2.5 billion trees in the Amazon—“temporarily turning one of the world’s largest carbon-capturing ecosystems into a giant source of carbon emissions.”

- The 2016 El Niño triggered a serious bout of glacier melting. This one will arrive when the polar ice caps are at their most fragile. New research shows that stronger El Niños may “speed up warming of deep waters in the Antarctic shelf, making ice shelves and ice sheets melt faster.

And what about India?

Our biggest worry is that El Niño will weaken the monsoon. When the wind patterns reverse themselves, places like Peru get torrential rains while we remain relatively dry. Ten of the 13 droughts since 1950 have been during an El Niño year. Here’s what we need to look out for:

One: Transition years suck—especially for India, according to experts:

As for the monsoon itself, if an El Niño state does emerge by summer, then we are more than likely to see a deficit monsoon. A transition from a La Niña winter (which we are in now) to a summer El Niño state tends to produce the largest deficit in the monsoon—of the order of 15%. This implies that the pre-monsoon and monsoon circulations tend to be weaker.

Two: As always, North India will suffer the most—with parts of Delhi, Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, and Chhattisgarh experiencing drought-like conditions. Central and northwestern India could experience severe heat waves.

Three: El Niño is terrible for our economy. Over the last 40 years, our growth rate was 5% in El Niño periods—compared to 6.6% in others. A bad monsoon is bad news for the agriculture sector—which accounts for 20% of our GDP. This, in turn, will send food prices soaring—and therefore the overall inflation rate. Last not least, the rural sector employs nearly half of India’s workforce—so El Niño’s no good for jobs data either.

But, but, but: As we noted before, these weather patterns are highly unpredictable: “For instance, even the strongest El Niño has given normal monsoon rain of 102% in 1997, while weak El Niño conditions resulted in severe drought in 2004 to the tune of 86%.” Indian monsoons are affected by a variety of factors. El Niño is just one of them.

The bottomline: Who knows what kind of El Niño cometh our way. We keep all our fingers and toes crossed as we wait.

Reading list

The Conversation has the best explainer on El Niño and La Niña—and looks at four likely effects. Grist and CNBC News have the most on the likelihood that we will cross the 1.5°C threshold. Weather.com, Tribune India and Quartz have the most on how El Niño will affect India. Mint looks at whether it will undermine rural India’s recovery. The Guardian has the latest research on the effect on glaciers.

souk picks

souk picks