A list of intriguing things

One: Moose usually have a boring brown coat—but Sweden boasts the rare and elusive white variety. There are about 100 of these fair & lovely creatures—out of a total population of 400,000 in Sweden. What makes them intriguing is that they are not albinos—which is typically the case with other species. These moose have a recessive gene that alters their skin pigment—and it has received an assist from hunters:

“Hunters have chosen to not kill any moose that are light,” said [professor at Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Göran] Ericsson. In other words, with white moose being effectively protected, natural selection might be making the condition more common. “It is kind of like dog breeding,” he noted. “They [hunters] choose to select for traits that otherwise wouldn’t have occurred.”

Fun fact: For all this talk of colour, and what is amusing is that moose are themselves colourblind. See rare footage of the magnificent white moose below. (Smithsonian Magazine)

Two: Here’s an early Halloween present—courtesy Harvard University. The institution recently made news for its decision to remove human skin from the binding of a 19th century book—‘Des Destinées de L’âme’ by Arsène Houssaye, a French novelist and poet. Yup, you read that right. Human skin.

The practice of binding books with human skin—called anthropodermic bibliopegy—dates back to the 16th century, but came back in fashion during the Victorian era. No, they didn’t kill people to bind books—but the reasons for their existence are no less creepy:

The historical reasons behind their creation vary: 19th century doctors made them as personal keepsakes for their book collections or at the request of the state to further punish executed prisoners. Persistent rumors exist about French Revolutionary origins as well.

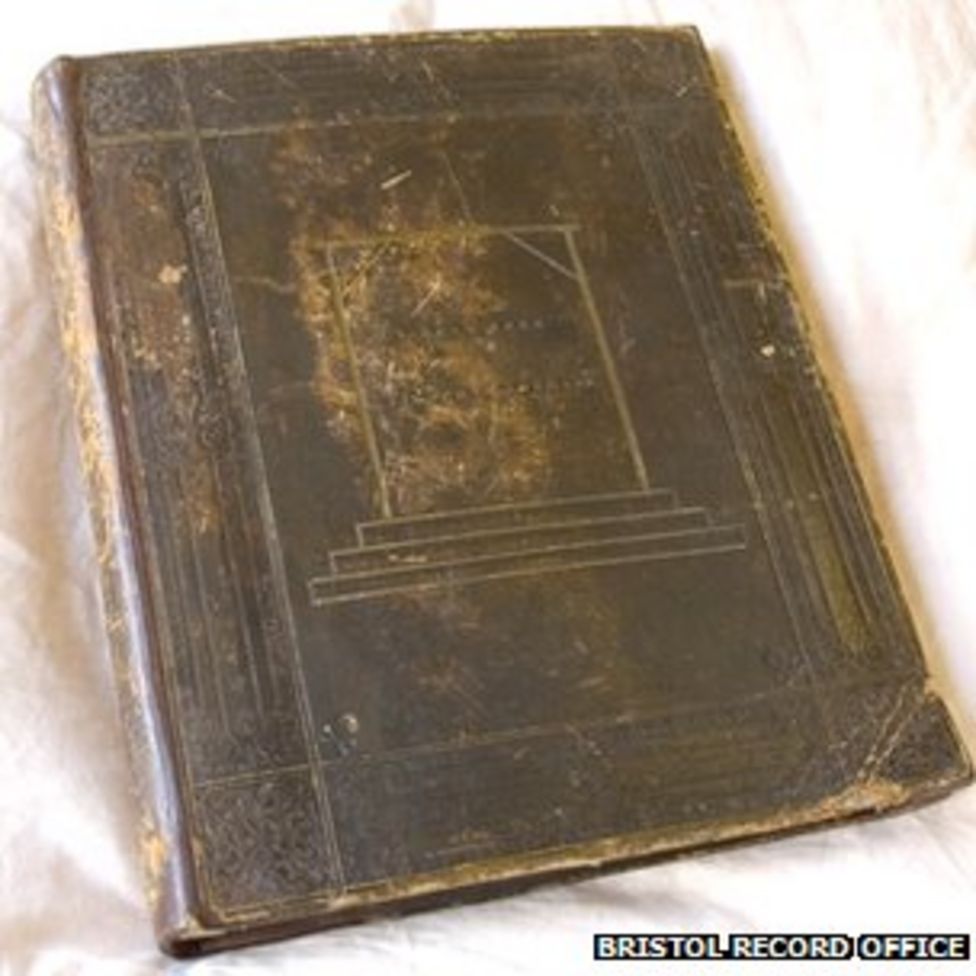

For example, the book housed at the Bristol Record Office contains details of a murder committed in 1821—and its brown cover was made with the skin of the murderer John Horwood. The Harvard book was bound by a French doctor who used the skin of a female psychiatric patient who died in 1880—without her consent. Bouland inserted a hand-written note that said: “A book about the human soul deserved to have a human covering. By looking carefully you easily distinguish the pores of the skin.” Talk about seriously gross!

If you really need more, New York Times reports on the Harvard story—while BBC News has the history of the practice. You can see the Bristol book below—which mercifully looks far less gruesome than it sounds.

Three: Say hello to Palmsy—a journaling app built like a ‘social networking app’. It allows you to post pretty much anything—with an option to add photos. Just sit back and watch the ‘likes’ adding up. But here’s the catch: All that appreciation is fake:

You can post on Palmsy, but those posts don’t go out to anyone, just as god intended. When it comes to the likes, the app simply sends you notifications by pulling random names from your phone’s contact list. Those people haven’t really liked your post, though. They’ve never even seen it.

In fact, you can even set a limit on the number of likes per post and for how long the posts get these fake likes: a few seconds, a few minutes, a few hours or a few days. Think of it as the perfect “social media methadone”—to wean you off the drug of Insta validation. Check out the app here. (Gizmodo)

souk picks

souk picks