Editor’s note: Editorial Manager Rachel John’s great grandfather migrated to Burma from Madras. About 30 years later, he—and his family of eight—would retrace their steps back to the homeland—fleeing the Japanese incursion during World War II. As with most refugees, they took nothing with them except tradition, language and—of course—food. Rachel looks back at the cuisine that shaped her childhood—along with their recipes—making it a double treat:)

Eating Burma: A family recipe story

Written by: Editorial Manager Rachel John

My first ever memory of food is of eager anticipation—of waiting as my mother slaved over the stove to make Ohn No Khow Swe. As a seven-year-old, I never never understood that the dish was a great labour of my mother’s love—the hours of chopping, frying, and grinding spent fulfilling her daughter’s wish. For years, I would get blank stares anytime I mentioned my favourite dish—until it became ubiquitous in Asian menus as the far more generic Khao Suey. These are but a pale imitation of the luscious coconut chicken broth-smothered fresh noodles of my childhood—topped with seenjay (garlic oil), fried noodles, fresh green onions and crushed chilli—the taste and smell of which instantly makes me feel like a child again.

At the time, it was just food. I didn’t understand that I was being nourished by my family’s culture and history. These dishes had travelled miles—in great peril—to make their way to our dining table.

Crossing borders and cultures

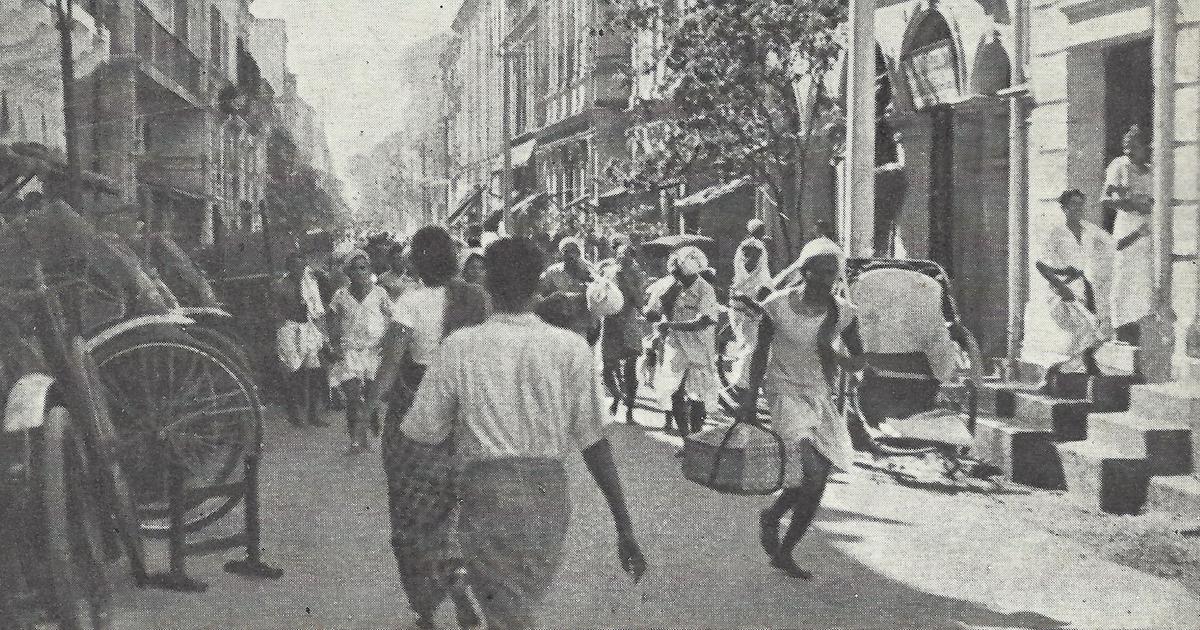

Indians migrated to colonial Burma in the early 20th century—to become low-ranking babus in the railways or at the office of the auditor general. But my maternal great grandfather came to Rangoon (present-day Yangon) from what was then known as Madras to work in a church. Burma soon became home for him and his growing family of seven children—including my aaya, my grandmother—his only daughter.

In 1941, Japan declared war against Britain in World War II, and set its sights on Burma. Few today remember the frantic exodus of Indians fleeing to escape the brutal military campaign. Historian Ranvijay Singh writes, “Nearly half a million Indians walked across some of the harshest tropics of Asia in order to escape the Japanese Army, and all that their regime would bring. Most endured the extreme climate, topography and terrible physical strain to reach the safety of India. Some never made it.”

Those who did—my aaya included—encountered a land that no longer felt their own. In a strange land, among strange people—there was only food to offer comfort. Everything else had been lost. Today, traces of that journey remain in Chennai’s Burma Bazaar—a legacy of countless families like mine.

OK, define ‘authentic’

I recently followed a fierce Twitter debate over what constitutes an “authentic” Khow Swe. I realised that the dish of my childhood would likely never qualify. I am hardly qualified to judge what is ‘real’ Burmese food. The food that my aaya brought to our family has traversed a long distance from its homeland.

So the recipes I share here make no such claims to authenticity. Each recipe is just a point in a long evolution shaped by labour, emotion and history. What started out as a Khow Swe in colonial Burma was transformed into a different Khow Swe in a refugee family’s kitchen in Chennai. Food is a lived experience, as Palestinian author Reem Kassis writes in the New Yorker:

Our emotions about what goes in our mouth are intertwined with our feelings about the person preparing the food, the conversation at the table, the cultural rituals around a dish’s consumption. When dining, the social context matters perhaps even more than the quality of the food.

And for those who can never return to places they left behind, food is the closest thing to home.

Now, on to the food…

Ohn No Khow Swe: This is a dish that our family prepares on special occasions—such as birthdays and on Christmas. Mostly because it’s quite labour intensive, but it’s all worth it in the end.

Ingredients (Serves 4-5)

Boiled noodles, preferably fresh egg noodles.

For the curry:

2 kg chicken

½ cup garlic

¼ cup oil

A 2 inch piece of ginger

2 medium onions plus 1 onion, fried

1 tsp turmeric powder

1 tsp red chilli powder

1 chicken stock cube

1 coconut or 4 cups of canned coconut milk

¼ cup gram flour

Salt to taste

4 boiled eggs, chopped

Coriander, for garnish

For the accompaniments:

4 to 5 green onions or scallions, chopped

1 bunch of coriander leaves, chopped

4 boiled eggs, chopped

1 onion, fried

Red chilli flakes

Fried noodles (take the fresh egg noodles and shallow fry them)

Garlic oil (add chopped garlic to oil and then heat it up till they become crispy)

Lemon wedges

Fish sauce (optional)

Preparation:

- Grind garlic and ginger into a paste. Grind the onions separately to form a smooth paste.

- Add oil to a large vessel and wait for it to heat up. On a medium flame, add the ginger-garlic paste and stir for about a minute.

- Add onion paste to the pot and fry till it starts to brown.

- Add turmeric and red chilli powder and stir for about two minutes, till the raw smell of the masala goes away.

- Then add the chicken to the masala, follow it with salt according to taste and sear for about five minutes.

- In the meantime, bring about 4 cups of water to a boil in a separate vessel. Once the chicken sears with the masala, add in the water and mix well. Throw in the stock cube at this point

- Increase the flame to high and let the curry come to a boil. Reduce heat to medium after the curry starts boiling and let it cook for about 30 minutes.

- While the curry cooks, extract the coconut milk if using a fresh coconut. Here’s a video on how to do that. You need to extract the milk twice—the first milk extracted will be thicker while the second will have a much watery consistency.

- Also, prepare the thickening agent: roast the gram flour in a dry pan till it's fragrant. Add the roasted flour to ½ cup of water and whisk well. Ensure there are no lumps.

- Coming back to the chicken after 30 minutes, add the second extraction of coconut milk and let it come to a boil. Add in the boiled eggs at this point.

- Then add the first extraction, mix well and let it boil for about 15 minutes on medium flame.

- If using canned milk, just put in all four cups in one go and let the curry boil for about 15 minutes.

- After that, add the prepared gram flour slurry and stir continuously till the curry thickens up.

- Switch off the flame after the curry reaches desired consistency. Add in the fried onions and coriander leaves.

- Plate it up by first adding noodles, then the broth and follow it up with the accompaniments in desired quantities. Don’t forget the all important lemon squeeze!

Eenjo: This shrimp-based soup is both simple and yet so hearty. It was reserved for days when I was low or unwell. The subtlety of the flavour was lost on me at the time but it was the ultimate comfort food, served with a zing of heat from ‘ngapi kyaw’—a magical coarse paste made with crushed red chillies and ngapi (fermented shrimp paste). Spicy beyond measure and soothing to the soul.

Ingredients

1 litre of water

2 medium onion, sliced

7 cloves of garlic, crushed (or more if you want)

½ inch of ginger, crushed

1/2 cup of dried shrimp, slightly crushed

1 cup moringa leaves

½ cup chopped bottle gourd (optional)

¼ tsp of fermented shrimp paste (optional)

1 tbsp pepper

Salt to taste

Fish sauce

Preparations:

- Bring the water to a boil in a large pot, add in the onions, garlic, ginger and shrimp.

- Let it boil for about 5 minutes and then add the moringa leaves, bottle gourd and the shrimp paste.

- Season with salt and pepper.

- Let it cook on medium heat for about 10 to 12 minutes and then serve. It can be topped with fish sauce and served with plain rice.

Atho: This cold noodle salad is a street delicacy—called Lettho in our home, where it is made with slight variations. The principle is still the same though. You mix together a bunch of delicious ingredients, with your hands of course, such as dried shrimp, gram flour, rice, noodle, cabbage, boiled potatoes, chill flakes, fish sauce, tamarind pulp and many more! What you get is the freshest and the most flavorful possible salad.

It’s usually topped with crushed fried chickpea fritters called be-gyun kyaw. It’s a unique confluence of flavours and textures where you get a little bit of everything—spicy, sour and umami.

Ingredients (Serves about 4)

3 cups cooked rice

2 to 3 tbsp red chilli oil

½ tsp of MSG, optional

Ground dried shrimp

3 cups boiled egg noodles

4 to 5 boiled potatoes, diced

4 boiled eggs

½ cup chickpea powder

1 cup tamarind juice or 1 lemon

Garlic oil (add chopped garlic to oil and then heat it up till they become crispy)

1 cup fried onions, reserve oil

Fish sauce, as required

Toasted peanuts, optional

Be-gyun kyaw or chickpea fritters (find the recipe here)

Preparation:

- In a bowl, first mix rice with the chilli oil, a couple of teaspoons of shrimp powder, MSG and fish sauce. Set it aside.

- In a larger bowl, combine noodles, potatoes (slightly mashed) and rice. Mix with your hands.

- Then add eggs, chickpea powder, shrimp powder, tamarind juice, garlic oil and mix with your hands once again.

- Top with fried onions and toasted peanuts with a drizzle of fish sauce.

- FYI, this salad is pretty customisable, please add and omit as per your taste.

- Also, you can watch this video, to figure out exactly how this salad is mixed by hand.

Mohinga: is considered the national dish of Burma. It’s a fish-based soup (yes, we love seafood and broths), made with catfish and generously flavoured with lemongrass and fish sauce. A key ingredient of the soup is finely sliced banana stem, coupled with crushed red chilli and ground turmeric. It is thickened with toasted ground rice and is served with rice vermicelli noodles. What I consider Burma’s response to a bowl of piping hot ramen. I remember when aaya first made it for us with great fanfare. Traditionally, mohinga is eaten for breakfast but this special dish took us through the entire day.

Ingredients (Serves 5 to 6)

For the fish:

1 kg catfish (basa can be used as an alternative)

2 lemongrass stalks, chopped

1 tsp turmeric powder

½ cup fish sauce

For the soup:

6 to 7 cloves of garlic

2 inches of ginger

5 lemongrass stalks

2 to 3 tbsp oil

1 cup chopped onions + 1 onion sliced

60 gm of banana stem, thinly sliced (if available)

3 tsp turmeric powder

2 tsp red chilli powder

½ cup rice

1 litre water

Rice noodles

For the toppings:

Boiled eggs

Fried onions

Chilli flakes

Coriander leaves

Preparation:

- Boil the catfish with turmeric, lemongrass and fish sauce for about 15 minutes. Reserve the liquid

- Grind garlic, ginger and lemongrass into a coarse paste.

- In a pan, add oil and fry the paste until fragrant along with the onions and banana stem. Once the onions start to brown, add turmeric powder and red chilli powder, fry till the raw smell of masala dissipates. Then add the catfish and turn the heat to low. Cover and cook for about 15 minutes.

- Place 1 litre of water to boil in a separate pot. In the meantime, dry toast the rice till it acquires a light brown colour and grind it. Add ground rice to cold water and mix it to form a slurry.

- Once the water starts to boil, add the rice slurry to it while stirring continuously to avoid lumps.

- Add the cooked catfish mixture to the water and bring it to a boil. Add the sliced onions and about 4 to 5 tablespoons of the liquid reserved after cooking the fish. Another stalk of lemongrass can also be added here to intensify the flavour.

- Once the soup starts boiling, lower the heat to a simmer and cook for at least 45 minutes. The longer it simmers, the better.

- Taste the soup and add more fish sauce if needed. Serve with rice noodles and desired toppings.

souk picks

souk picks