Simply Shergil: A guide to a legendary woman painter

Editor’s note: This colourful essay on the history and art of Amrita Shergil was first published on The Heritage Lab—a wonderful resource of stories on cultural heritage, art, museums and lots more. You can find other wonderful essays on art and culture over at their website.

About the lead image: This painting is called the ‘Bride’s Toilet’. It’s part of a South India trilogy where Amrita Shergil was inspired by an Ajanta mural.

There are few in India who are unfamiliar with the name of ‘Amrita Shergil’. The popular artist, an icon for many, even has a road named after her in Delhi! However, the narrative about Amrita has largely been focused on her personal / social life rather than her artistic journey and achievements; or the trends she set when it came to modern Indian art. So let us dive right in!

Before the Calcutta Group came into prominence (1943) and way before the Bombay Progressives (1948), came the art of Amrita: a mix of two different worlds, straightforward, unapologetic and real, just like her personal self.

So who was Amrita, and where did she come from? Watch the introductory video which refers to some of her best known works, and letters.

Amrita Shergil’s Women

Three Girls (1935): Even back then, Amrita’s work wasn’t everyone’s cup of tea. Did you know that the Nawab Salar Jung III (Prime Minister of the Nizam of Hyderabad), rejected the famous “Three Girls painting”? According to Karl Khandalavala, an art collector from Mumbai in the 1930s, Amrita lacked the tact to sell her works and market her art. This is reflected in Yashoda Dalmia’s biography of Shergil, where the Salar Jung incident finds mention. Amrita had apparently seen the Nawab’s collection, and remarked that it was junk, and that he should have collected the Impressionists instead. [Has this thought ever crossed your mind while visiting the Salar Jung Museum?]

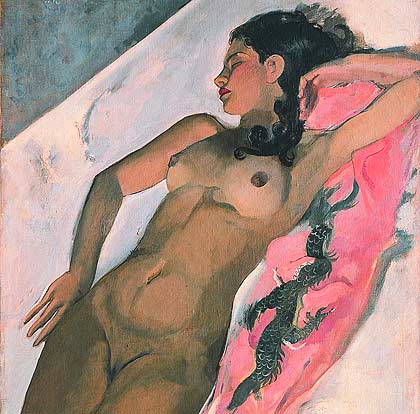

Sleep (1932): Amrita and her art has always said it as it was. During the time she painted, Indian art was mostly about landscapes, and relied heavily on mythology. The women in paintings were often characters from ancient Indian literature or mythology. Even though she began with painting portraits of her sister, friends and cousins, it was with this nude of her sister that she really experimented with the female body.

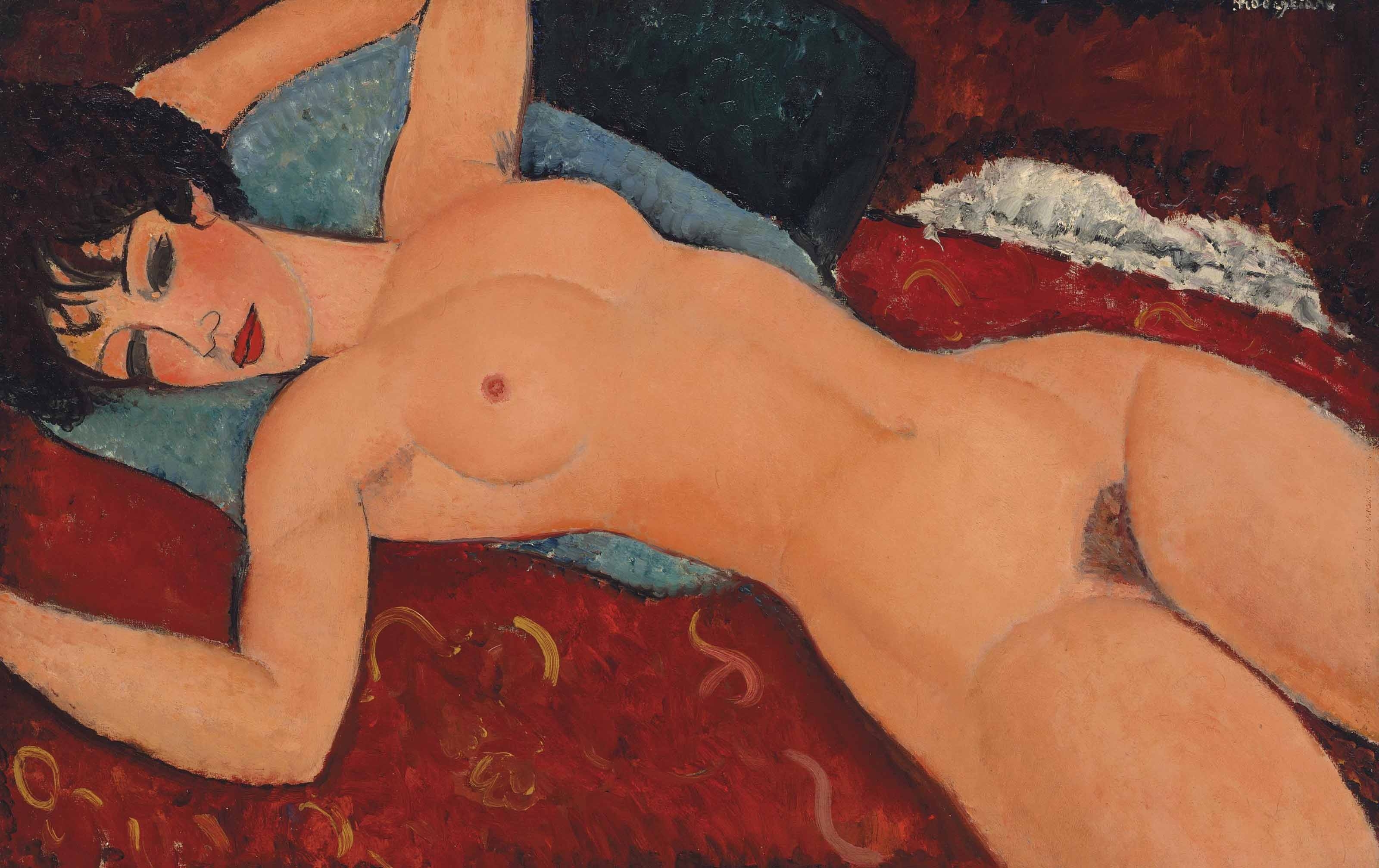

The influence of the Italian artist Amedeo Modigliani is unmistakable. See Modigliani’s painting below.

The influence of the Italian artist Amedeo Modigliani is unmistakable. See Modigliani’s painting below.

Young Girls (1932): Later, yet another painting of her sister won her a prestigious Gold Medal from the Grand Salon. Amrita was only 19 when she won the award! Take a minute really, to think about what you are / were doing at the age of 19, and you’ll know why Amrita remains to be a prodigal inspiration for many women artists!

Young Girls (1932): Later, yet another painting of her sister won her a prestigious Gold Medal from the Grand Salon. Amrita was only 19 when she won the award! Take a minute really, to think about what you are / were doing at the age of 19, and you’ll know why Amrita remains to be a prodigal inspiration for many women artists!

In this painting, “Young Girls”, it is believed that while the subjects were Indu (her sister) and a French friend in conversation. The two women, one poised and assured, the other more awkward with her face buried beneath streaming hair, have been believed to be embodying different sides of the artist herself.

In this painting, “Young Girls”, it is believed that while the subjects were Indu (her sister) and a French friend in conversation. The two women, one poised and assured, the other more awkward with her face buried beneath streaming hair, have been believed to be embodying different sides of the artist herself.

Amrita Shergil: the painting style

Even though Amrita came from a very privileged family, her art reflected the rural poor and mostly centred around women. During her time in Paris, she chose to paint the grim reality of the glitzy glamorous Paris. Like in this one, she painted a professional model—one that looks tired, with a body fading away. She didn’t make her nudes in a way that was erotic or sensuous; her art reflected reality and the nudes never met the gaze of the viewer.

Indian art traditionally tended to be sketchy and sentimental, but Amrita was determined to find a new way of showing the reality of the country that her father had taught her to love. Her art from her time in India is marked by angular faces and big eyes; and the women are suddenly more relatable and real.

Amrita Shergil’s time in India

The themes in her artwork during this time cover her servants, camels, cart drivers, tribal women, women working, taking care of children and here’s an interesting thing to observe : compare the difference between “Young Girls” and “Woman on Charpoy”.

While Young Girls is about unmarried women from a different time and space, Woman on Charpoy is about married women, with household responsibilities. Right from the clothing to the interaction, Amrita Sher-gil captures the moment as it is.

While Young Girls is about unmarried women from a different time and space, Woman on Charpoy is about married women, with household responsibilities. Right from the clothing to the interaction, Amrita Sher-gil captures the moment as it is.

‘There are such wonderful, such glorious things in India, so many unexploited pictorial possibilities, that it is a pity that so few of us have ever attempted to look for them even (much less interpret them)…’

Emotion in Shergil’s paintings

If realism defined Amrita’s art, ambiguity was its hallmark. Look at her paintings from NGMA, New Delhi or this one above. Are the figures hopeful or without life? Are they celebratory or sacrificial? Are the women in control, or are they submitting to their fate? Even in Woman Resting on Charpoy – is the woman relaxing or tired / ill?

The Colours in Amrita Shergil’s art

The Colours in Amrita Shergil’s art

Amrita’s painting style used bold colours and contours, keeping the subject / a certain person always looming large in the foreground. Her body of work in India experimented with earthy colours – reds and browns. In her own words :

In Europe I felt that I have to go away from this kind of greyness and from this strange light in order to be able to breathe. Here everything is natural. There I was not natural and honest because I was born with a certain thirst for colour and in Europe the colours are pale – everything is pale.” She mused that “the colour of the white man is different from the colour of the Hindu and the sunshine changes the light. The white man’s shadow is bluish-purple while the Hindu has golden-green shadow. Mine is yellow. Van Gogh was told that yellow is the favourite colour of the gods and that is right.”

Amita’s inspiration

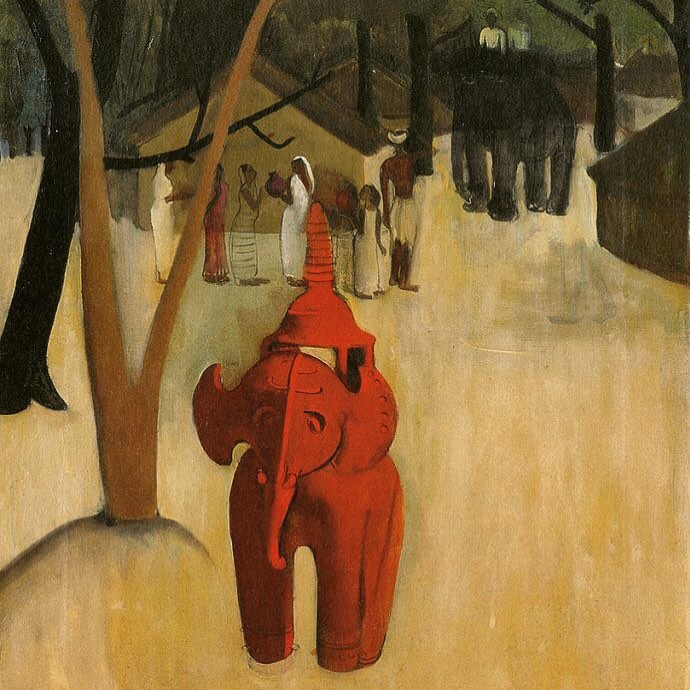

While in Europe, Amrita’s work reflected her exposure to artists such as Paul Gaugin. Her self-portraits were pretty much a reflection of the artists she admired. In India, she was exposed to the Ajanta murals and Mughal / Pahari schools of art. Her body of work then started reflecting her observations.

Like the figures from the Ajanta frescoes, rounded and simplified like wooden effigies, the figures in Bride’s Toilet and Brahmacharis sit grouped in rhythmic arrangements, painted in varying shades of yellow, red and brown. Even in the Vina Player (now at the Lahore Museum), the faces and their structure resemble those in Ajanta frescoes, as does the colour scheme. The use of white and shading is yet another common feature in both Shergil’s art as well as the murals of Ajanta.

In a letter to Karl Khandalavala in 1940, she said:

The Mughals have taught me a lot. Looked at rightly, the Mughal portraits can teach one everything almost that matters. Subtle yet intense, keenness of form, acute and detached somewhat ironical observation, all the things I needed most at the time I got acquainted with them.

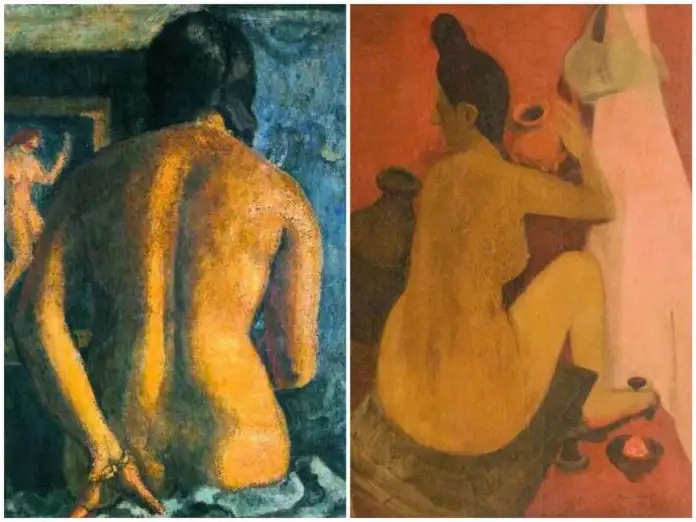

While her essential subject didn’t undergo a change, Amrita’s way of looking at them did. Sample these two paintings: the Torso and the Woman Bathing.

Amrita Shergil, the legacy

Painting was her superpower, but Amrita was a prolific writer too. A lot about her life is now in public domain because of her letters – she wrote frequently to her mother, her sister and her friends. Her parents actually burnt a lot of the letters written by Amrita fearing they’d get into wrong hands – and she was furious! She died at the age of 28, just days before her art show in Lahore (then, part of undivided India).’

Today more than 100 of her paintings are at the NGMA, New Delhi, some with the Kiran Nadar Museum, the DAG and yet some with private collectors. As a National Treasure Artist, Amrita’s paintings cannot go out of India to be sold and she remains to the most expensive Indian female painters.

In 2018, Amrita Shergil’s painting “the little girl in blue” sold for a record 18.69 crore.

The painting along with others was unveiled at Sher-Gil’s inaugural exhibition at Faletti’s Hotel in Lahore. The subject is Amrita’s then-eight year old cousin Babette Singh Mann; the painting was commissioned by Babette’s mother, Lady Buta. As the story goes, she was quite unhappy and rather aghast at this portrait which did not “look realistic enough” and “did not make Babette look pretty enough”.

souk picks

souk picks