The little clay cart

Editor’s note: This insightful history of ‘Mricchakatika’—the ancient Sanskrit drama—and its relevance even today was first published on The Heritage Lab—a wonderful resource of stories on cultural heritage, art, museums and lots more. You can find other wonderful essays on art and culture over at their website.

‘Mricchakatika’, (The Little Clay Cart), is one of the earliest known Sanskrit dramas. It has been widely performed across the world owing to several successful 19th century translations. The iconic ten-act play, loved for its intriguing (and sometimes unbelievable) plot-twists, satire and characterization, continues to be enacted to this day.

The play’s international productions often came to be named after its central character — Vasantasena. She is even featured in artworks by renowned artists like Raja Ravi Varma, Abanindranath Tagore, and YG Srimati. In 1931, the play was adapted into the first silent Kannada film starring Kamladevi Chattopadhyay. In 1984, it inspired the critically acclaimed Hindi movie ‘Utsav’, helmed by Rekha, Shashi Kapoor, and a young Shekhar Suman — directed by theatre veteran Girish Karnad.

This is Vasantasena painted by Abanindranath Tagore:

Here is Rekha as Vasantasena in Girish Karnad’s ‘Utsav’ (1984):

What makes Mricchakatika so timeless?

Arthur W Ryder, who translated the play to English in 1905, writes in the preface to his translation:

Nowhere else in the hundreds of Sanskrit dramas, do we find such variety, such drawing of character; and nowhere else is there such humour… From farce to tragedy, from satire to pathos, runs the gamut with a breadth truly Shakespearean…The humor has an American flavor, both in its puns and in its situations running the whole gamut, from grim to farcical. from satirical to quaint. Its variety and keenness need not fear comparison with the greatest of Occidental writers of comedies.

The play is attributed to ‘King Shudraka’ who is generally believed to have lived sometime between the 3rd century BC and the 5th century AD.

Unlike the works of other Sanskrit playwrights (Kalidasa or Bhavabhuti), this play focuses on the everyday lives of common people in an ancient Indian kingdom. A storyline involving love, loyalty, friendship and a political coup, sprinkled with humour and satire is rare in Sanskrit dramas.

Mricchakatika: Storyline and characters

The play is set in Ujjain — a prosperous, urban Indian society — one which places importance on wealth and gives women who are married, a higher status. In the first act itself, we are introduced to Charudatta, a wealthy noble-man who has fallen on hard times.

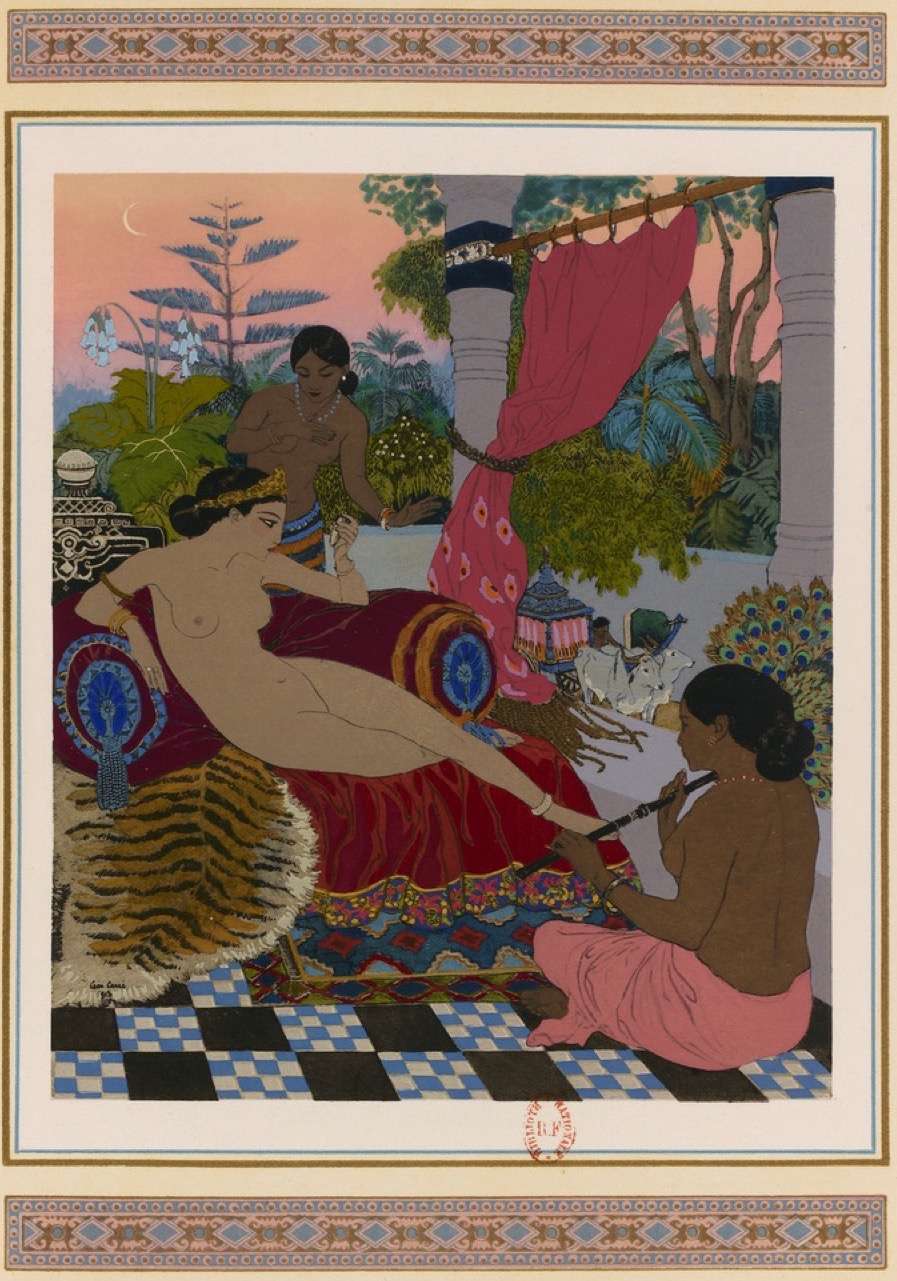

Then we meet Vasantasena, a beautiful courtesan (nagarvadhu) who longs to marry Charudatta:

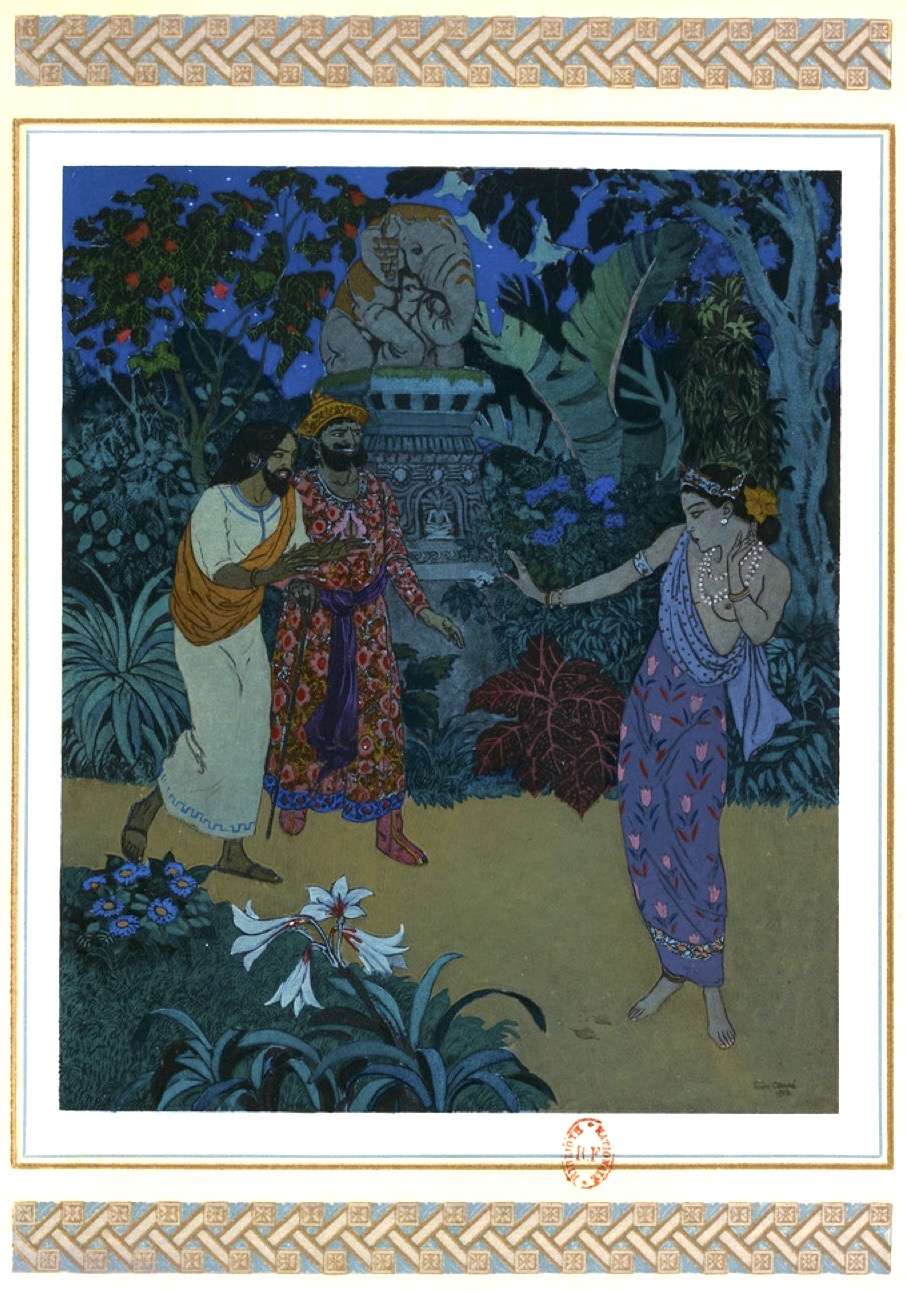

And Samsthanaka, the evil brother in law of the King, who is determined to ‘conquer’ Vasantasena’s attention.

As the plot unfurls, we are introduced to a range of characters amidst a political revolution that is brewing in the backdrop. The revolution seeks to overthrow an unjust, tyrannical King. The play is thus relatable to a reader of any time or place because of its universal characters and storyline.

As the plot unfurls, we are introduced to a range of characters amidst a political revolution that is brewing in the backdrop. The revolution seeks to overthrow an unjust, tyrannical King. The play is thus relatable to a reader of any time or place because of its universal characters and storyline.

Shudraka’s ‘Mricchakatika’ takes us into a world of contingencies, where the fate of each character is intertwined with that of another. The play begins with Vasantasena running into Charudatta’s house on a stormy night, while being chased by Samsthanaka.

This is Shakara hiding behind vita (his attendant):

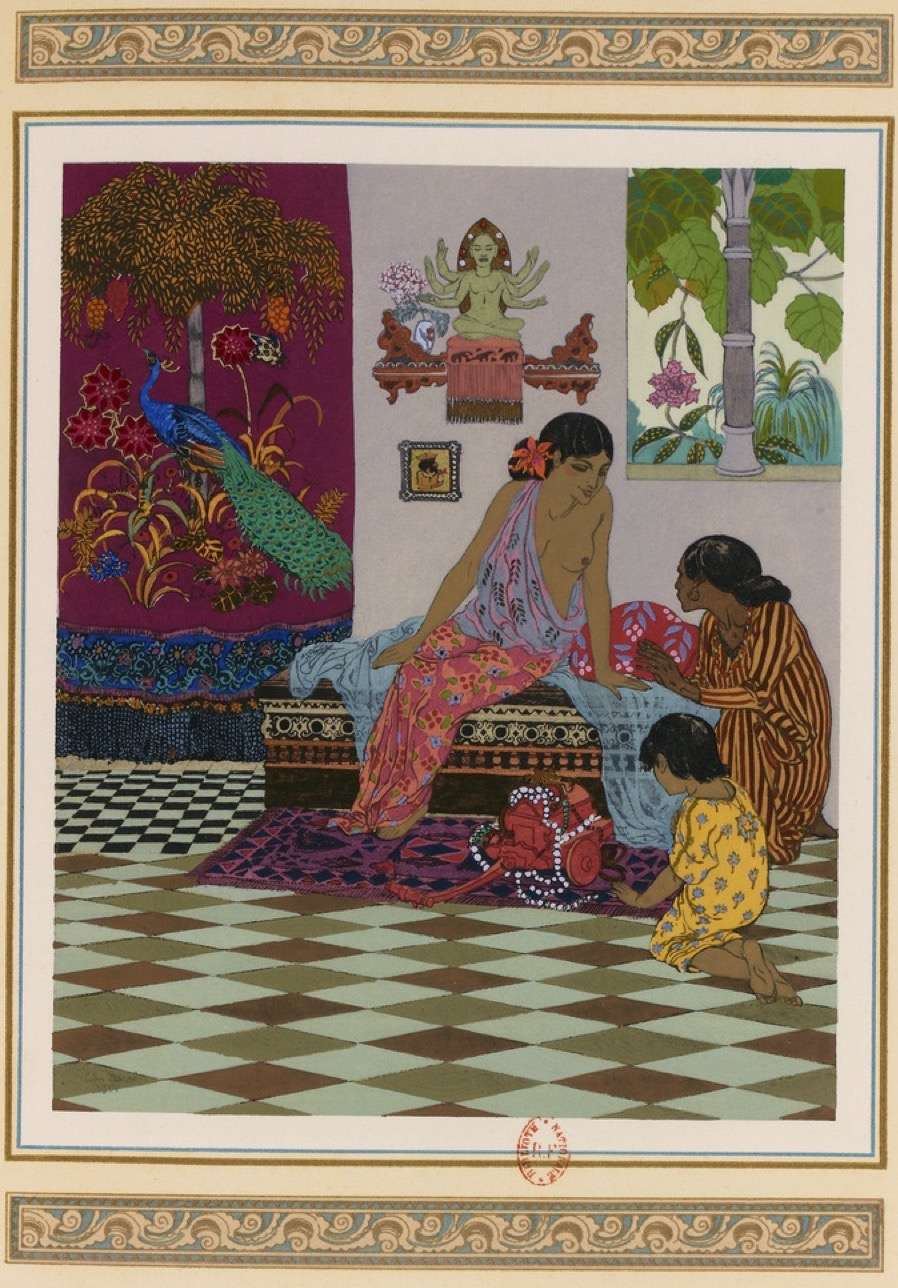

She entrusts Charudatta with her jewels, before walking to her palace. Back home, Vasantasena confides in Madanika (her attendant) about her love for Charudatta. Meanwhile, Sarvilaka, a thief breaks into Charudatta’s home and steals the jewels with the hope of using them as a ransom to secure Madanika’s (his love interest) freedom. The next day, when Sarvilaka brings the stolen jewels to Vasantasena, she quickly understands the situation and releases Madanika of her duties.

When the theft is discovered, Charudatta’s wife, parts with her only pearl necklace to save her husband’s honour. She has their friend Maitreya deliver it to Vasantasena with an apology; the latter accepts the necklace seeing it as an opportunity to visit Charudatta’s home again. Her love for Charudatta even prompts her to rid a gambler of debt. The gambler eventually becomes a monk and returns at a crucial moment in the play.

At Charudatta’s home, Vasantasena meets his son, crying for a golden cart. She puts her jewellery in his cart, and while the child becomes happy, it is this innocent act that leads to Charudatta’s implication in Vasantasena’s murder later in the play. The crafty Samsthanaka, seething from anger at Vasantasena’s rejection, strangulates her, and frames Charudatta. Her jewels found in the clay cart serve as circumstantial evidence against Charudatta.

However, Vasantasena isn’t dead (the gambler-turned-monk saved her)! Towards the end, just as Charudatta is being (hastily) sentenced for her murder, she rushes into the Court preventing the unjust execution. To a reader today, this might sound like a familiar trope; in ancient Sanskrit drama though, this was a first.

In the climax of the play, Samsthanaka and the King are overthrown; Charudatta and Vasantasena are united in matrimony; the new King grants Charudatta the fiefdom of an adjacent city, restoring his wealthy-status; Madanika is able to secure her freedom; even the gambler-turned-monk is made the chief of all monasteries.

The characters of the play might have been developed centuries ago, but the overarching themes of love, poverty, power, politics and fighting oppression continue to resonate universally. Perhaps it is this that makes the play so timeless.

‘Mricchakatika’ also sets itself apart from its contemporaries in the way that instead of drawing from Indian mythology, it is strongly rooted in secular traditions. In many ways, the play draws on the Buddhist teachings of compassion and generosity and adopts the universal view that ‘all is well that ends well’.

The significance of the play’s title ‘Mricchakatika’

When Vasantasena places her jewellery in the terracotta cart, she elevates its value for the child. By the end of the play, every ordinary character (like the humble clay cart), stands “elevated” in social status. Their lives are transformed because of an ongoing chain of generosity, compassion and love.

When Vasantasena places her jewellery in the terracotta cart, she elevates its value for the child. By the end of the play, every ordinary character (like the humble clay cart), stands “elevated” in social status. Their lives are transformed because of an ongoing chain of generosity, compassion and love.

The clay cart is central to a child’s make-believe world where everything is okay in the end. In the real world, it might not necessarily turn out to be so, but the playwright invites us to find that optimism and participate in the cycle of kindness.

The many shades of Vasantasena in adaptations of ‘Mricchakatika’

‘Mricchakatika’ has enjoyed several translations, adaptions and stage productions around the world. The visual depiction of the play in photos or ephemera across geographies and cultures, is also telling of the variety of ‘oriental’ interpretations. From the landscape to costumes, the representation of ‘exotic’ India remains quite consistent — this difference becomes even more stark as we compare the Indian interpretations of the play.

In 1826, ‘Mricchakatika’ was translated as ‘The Toy Cart’ by Horace Hayman Wilson, a surgeon in the East India Company. In 1847, the text was translated by the German scholar AF Stenzler, and published in Bonn. Subsequently, translations appeared in Bengali (1899) and Marathi.

In 1850, ‘Le Chariot d’enfant’ premiered in Paris. This is what Victor Barrucand said about the play in 1895:

I admit that nothing in the Greek, English and French theater seems to me superior to this Indian comedy.

Over the years, the play was adapted to be performed in Amsterdam (1897), Sweden (1894), Denmark (1870), Italy (1872), and Russia (1849).

Over the years, the play was adapted to be performed in Amsterdam (1897), Sweden (1894), Denmark (1870), Italy (1872), and Russia (1849).

Mricchakatika: 20th century adaptions

Lion Feuchtwanger, a German-Jewish playwright, worked on an adaptation during 1915-16; the play was first performed at Mannheim in 1916 and became one of the most successful productions of the time. These were the initial years of the First World War and Feuchtwanger, having read Shudraka’s work, was convinced that “Indian philosophy, with its stress on infinite kindness, calm and wisdom would conquer the West”. After a world premiere at the Grand Ducal Court and National Theatre Mannheim, it was staged over a few years, with more than a hundred performances, such as at the Stadttheater Halle, at the Münchner Kammerspiele and in Berlin at the Theater am Bülowplatz.

About the image above: The premiere of Feuchtwanger’s Vasantasena had taken place in Mannheim in 1916. After further stages, the play finally had its premiere on February 8, 1918 in Munich. However, Lisa Kresse did not appear in the role of Vasantasena, but in a supporting role as a dancing companion of the same. Contemporary postcards show her in this role in a photograph by the Munich photographer Anna Steige.

Arthur W Ryder’s translation of ‘Mricchakatika’ to English in 1905 continues to be one of the most popular. Ryder’s version was enacted at the Hearst Greek Theatre in Berkeley in 1907, and in New York in 1924 at the Neighbourhood Playhouse, at the Potboiler Art Theatre in Los Angeles in 1926, and at the Theatre de Lys in 1953.

Interestingly, in the 1950s, Habib Tanvir, the noted Indian playwright travelled across Europe with the hope of producing Mricchakatika.

In 1996, writing for the Seagull Theatre Quarterly, Tanvir recollected his travels to Belgium, Germany and Poland in the hope of securing production partners for his adaptation of Mricchakatika (It Must Flow: A Life in Theatre). Eventually he produced the play in India as ‘Mitti Ki Gaadi’ — with a mixed cast of urban and rural artistes from Chattisgarh. It was one of his early works and cemented his position as one of India’s finest theatre directors. You can watch a recording of an open-air performance at IGRMS Bhopal here: Part 1 and Part 2. (1999).

The play has since been directed by eminent Indian playwrights and directors including Balwant Gargi (1960s), Ebrahim Alkazi (1970s) and has been performed in different languages including in English (Bangalore Little Theatre, 1963).

souk picks

souk picks