French connection: Lakmé's origin story

Editor’s note: This colourful essay on Lakmé's history was first published on The Heritage Lab—a wonderful resource of stories on cultural heritage, art, museums and lots more. You can find other wonderful essays on art and culture over at their website.

About lead image: This is the wrapping paper for confectionery products named after the famous opera — “Lakmé”. Illuminated by a strong lamplight, the deli basket logo of csemege kereskedelmi vállalat is visible.

A cross-cultural story about forbidden love between a Westerner and an Indian isn’t an unfamiliar story plot today. Back in the 19th century, when oriental subjects were a hot trend in art, this plot found itself playing out in an opera that would go on to achieve an iconic status in the years to come.

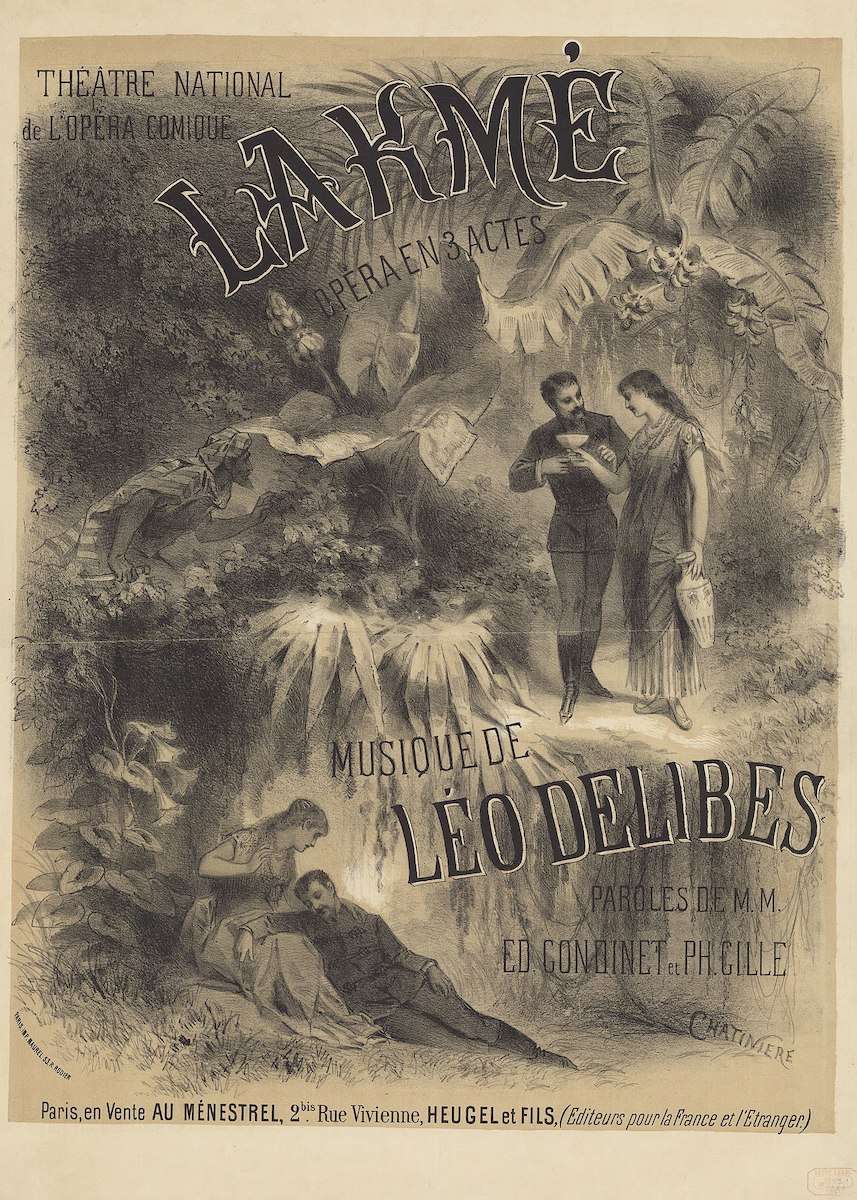

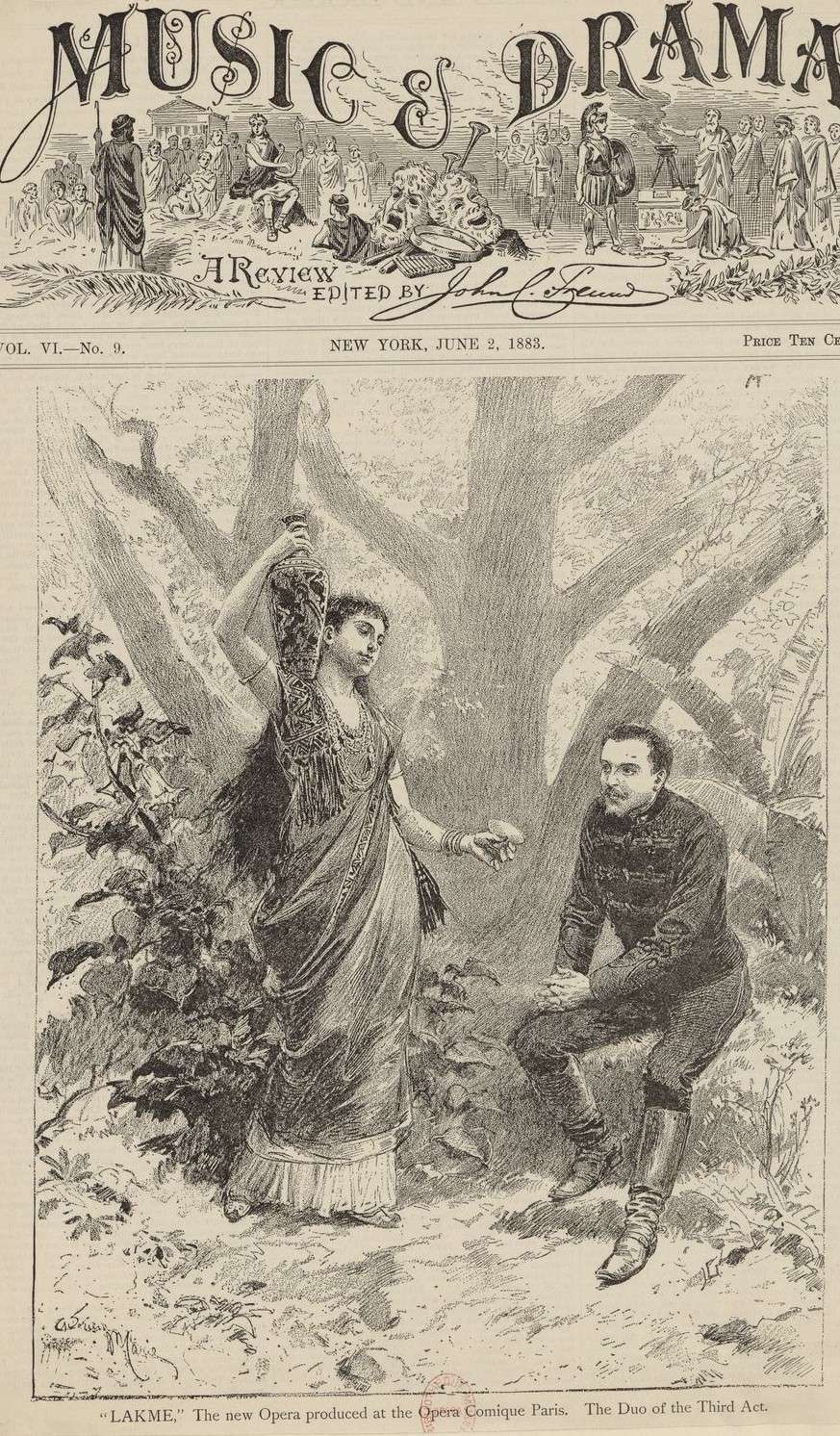

Lakmé, derived from ‘Lakshmi’ (the Hindu Goddess of wealth known for her beauty) premiered in April 1883 at the Opéra Comique Paris and became an instant success. It was performed over 1500 times (at the same venue) and performances continue to this day.

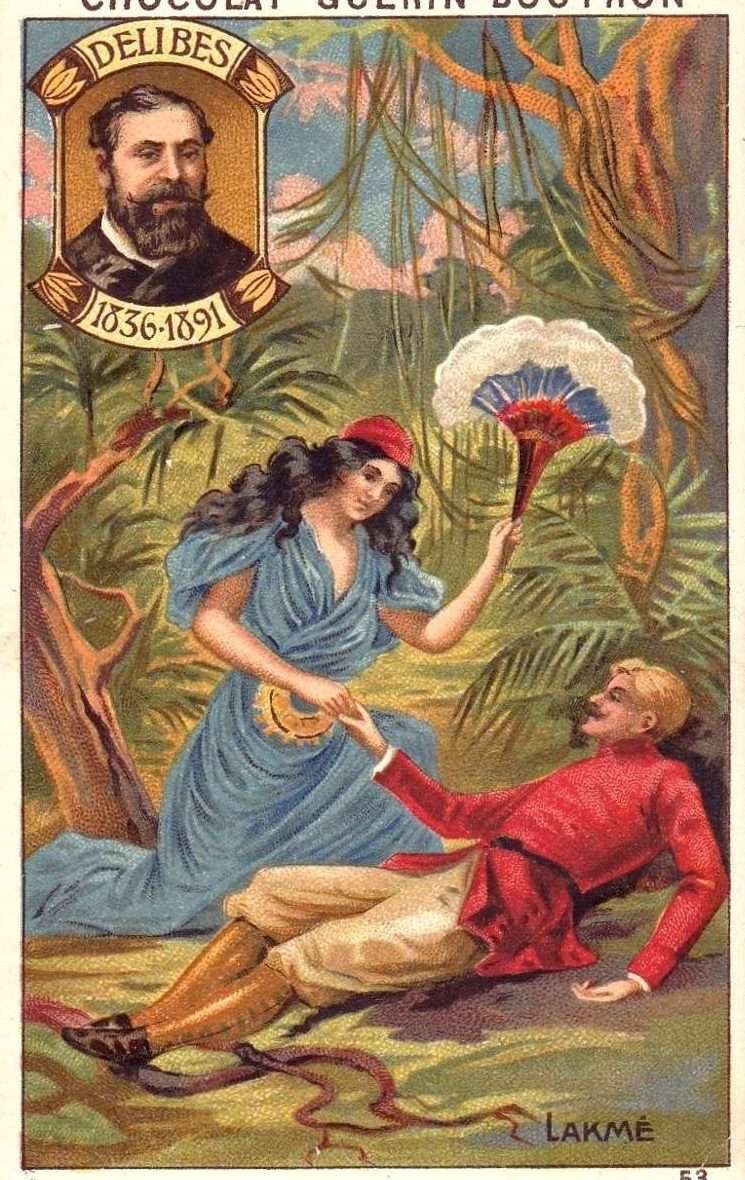

The plot of the three-act opera set in 19th century British India revolved around a tragic love tale between an English soldier and a Hindu priest’s daughter ending in her suicide (sacrifice). The opera is considered to be one of the most well known works of the French composer Léo Delibes (1836-1892). To its viewers, it offered an exotic view of India; nearly seven decades after it was first performed, the title of opera served as an inspiration for independent India’s first homegrown cosmetic brand that would alter the ‘oriental’ lens Indian women had been viewed with.

India, the spectacle

Operas before Lakmé too featured a stereotypical image of India — in India everything was sacred, mysterious, & mystic; also lacking agency, removed from reality and largely ignorant. In other words, India was far removed from the ideals of Enlightenment that Europe identified with.

Through the sets, music, costumes, make-up — an opera like Lakmé propagated and reaffirmed an exotic view of India held by European audiences. They displayed the opposing worlds of Western civilisation and Eastern backwardness.

Women were likely to be associated with nature inspired-imagery (springtime, flowers, birds) and could be broadly categorised as ‘femme fatale’ (the seductive one who causes trouble) or ‘femme fragile’ (the delicate, pure one who sacrifices). The people — men like Nilkantha were violent; and so on.

The “orient” was thus, largely conjured by Europeans who had travelled to India & sought to ‘see’ all they had heard; and was recreated / reshaped by those who had never set foot outside Europe. Léo Delibes fell into the latter category but Lakmé did have roots in the works of someone who could well fall into the first category. Enter, Theodore Pavie.

The scholar whose writings inspired Lakmé

In the year 1839, Théodore Pavie, a French orientalist & scholar, having learnt & taught Sanskrit, had the opportunity to travel to India. Here he visited Madras, Bombay, Poona, Calcutta and Pondicherry. Spending two years in India prompted him to write a series of short stories about love & vengeance titled ‘Scenes et recits des pays d’outre-mer’ (Scenes & Stories from Overseas countries).

According to Cronin and Klier, Lakmé is based on Theodore Pavie’s work ‘Les Babouches du Brahmane’ and other stories; previously, Lakmé has been dubiously attributed to Pierre Loti’s ‘Rarahu’ / ‘The Marriage of Loti’.

Les Babouches du Brahmane: In this story you meet the Brahman (priest) Nilkantha who avenges two British soldiers. The soldiers had humiliated him by placing slippers on his head during his prayers while making sexual advances towards his daughter Rukmini. Later, Nilkantha tricks one of the soldiers into buying a bouquet of (poisonous) flowers to present to his English fiancé.

Pavie’s other tale ‘Soughandie’ features Lakshmi’s as the brides of Vishnu (a take on the Devadasi tradition); Sougandhie, the daughter of a Lakshmi (Lakmé) falls in love with a young British officer, but they do not unite.

Scholars have analysed other works by Pavie, his letters from India to his father and concluded that the scholar liked romanticising India — though he remained true to reality and neither of his stories end in marriage. It is also interesting that in his stories it is the Westerner that dies.

But it is not only the storyline that seems inspired, it is also the description of the places that the story is based in, as pointed out by Cronin & Klier:

Interestingly, Pavie had never been told about “the inspiration”, until the time the opera travelled to his hometown, Angers (France).

At a dinner gathering, when asked about the inspiration for Lakmé, Leo Delibes’ collaborator Philippe Gille promptly mentioned the stories by “some Pavie”. When told that he lived in the same town, Delibes & Gille, having sought no permission from Pavie, feared that he would get upset. They ended up inviting him to the opera (the only royalty he would ever receive) and never mentioned the attribution again.

Pavie wasn’t the only orientalist to have influenced Delibes. The 1789 ‘Airs of Hindoostan’ by William Hamilton Bird was another work in the pursuit of “oriental learning” and perhaps Delibes was not entirely unfamiliar with it.

But wait… why would a French composer situate an opera in India & feature a British (rival colonial power) military officer in the lead?

In the essay Imperialisms: Historical and Literary Investigations, Linda and Michael Hutcheon write:

[I]t is important to recall that Opera was a powerful discursive practice in nineteenth century Europe, one that created, by repetition, national stereotypes that, we argue, are used to appropriate culturally what France could not always conquer militarily.

In 1757, after the British established victory in Plassey & cemented their position in India, there was little scope for French expansion. The battle, though, continued in art and literature of the time. In early 19th century Britain, there was a strong opposition to “mixing with Indian natives romantically”. By 1820, it had become socially unacceptable for British soldiers or officials to marry Indian women. The opera thus took a jibe at British morality and their ways in India; it also highlighted their negative influence in the subcontinent, and added the anti-British sentiment in India to the discourse.

In a sense, the story of Lakmé is the story of India; the British first allured by her jewels, seduces her — leading to her doom. The wrath of Nilkantha is the representation of uprisings against the British.

Lakmé : The French connection

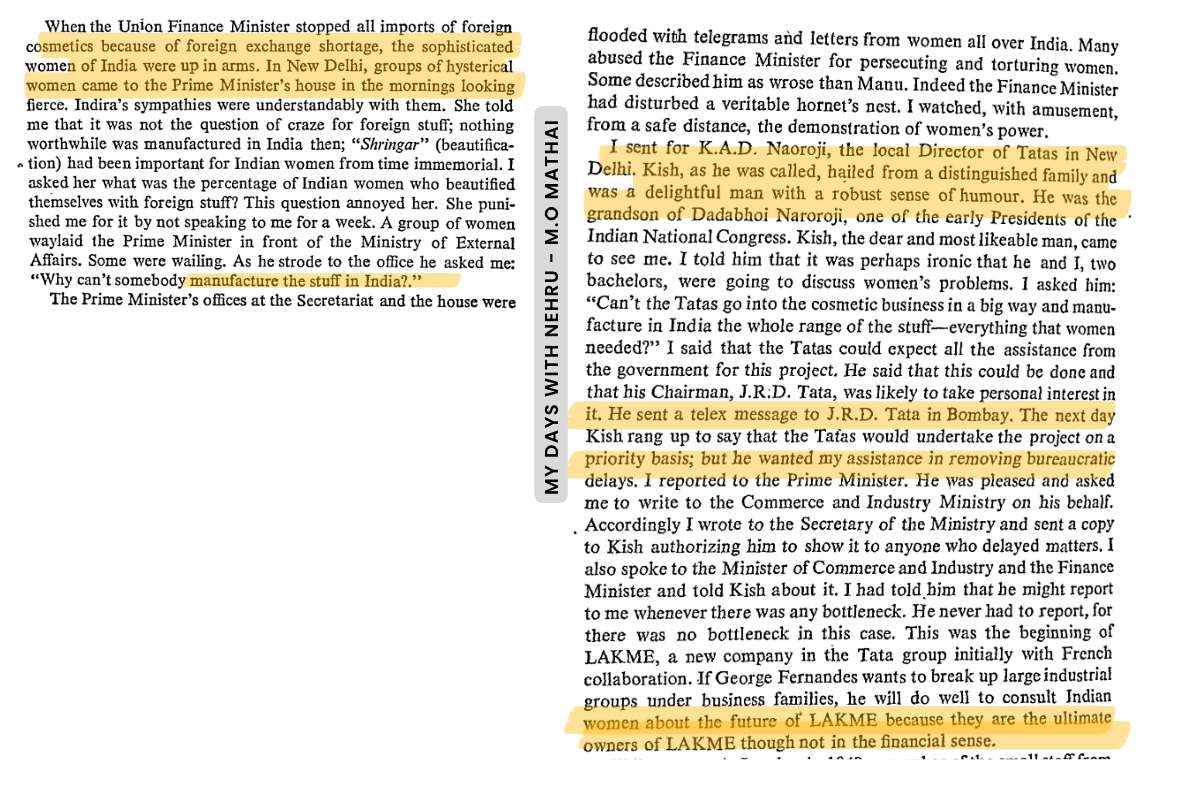

In the 1950s, a newly independent India seeking to stimulate domestic industry and manufacturing, introduced a ban on the import of foreign soaps, perfumes and cosmetics. The only problem was that India did not have a domestic cosmetic industry to protect.

The then Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru turned to the entrepreneur JRD Tata for a solution; the Government of India extended all possible support to set up an industry that would be “owned by all women of India”.

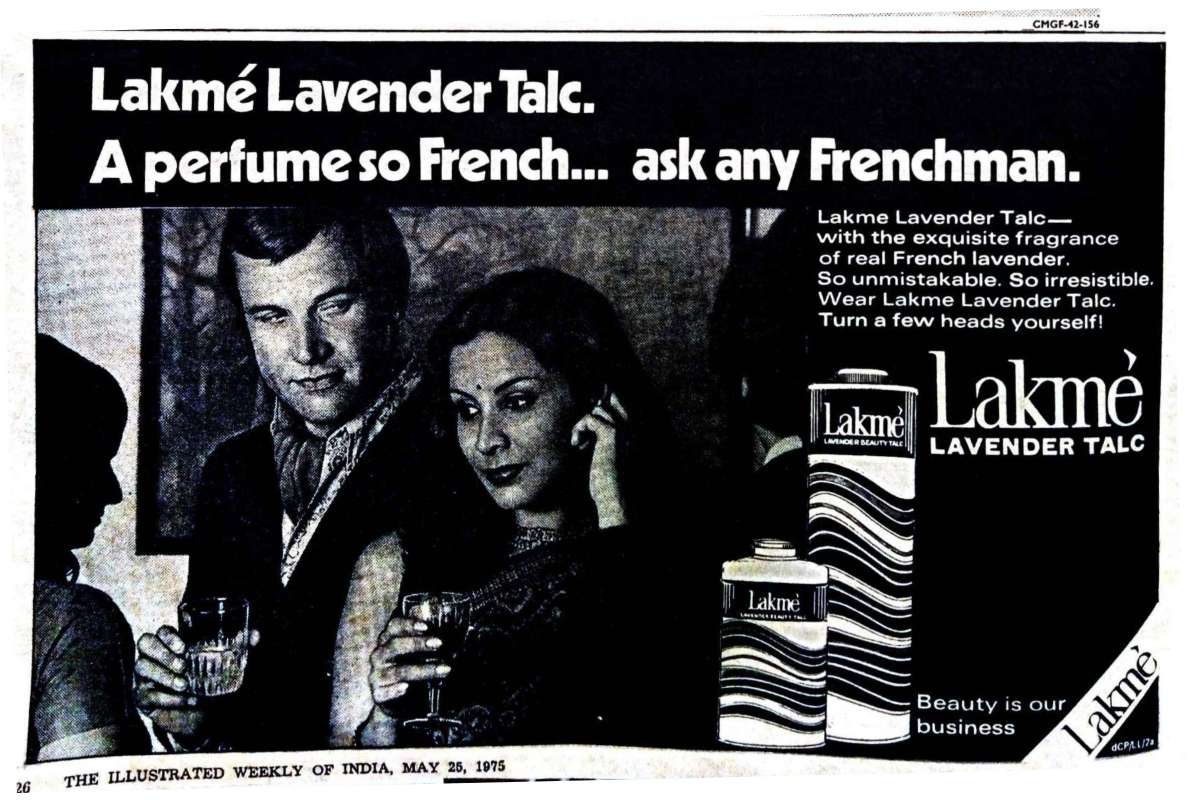

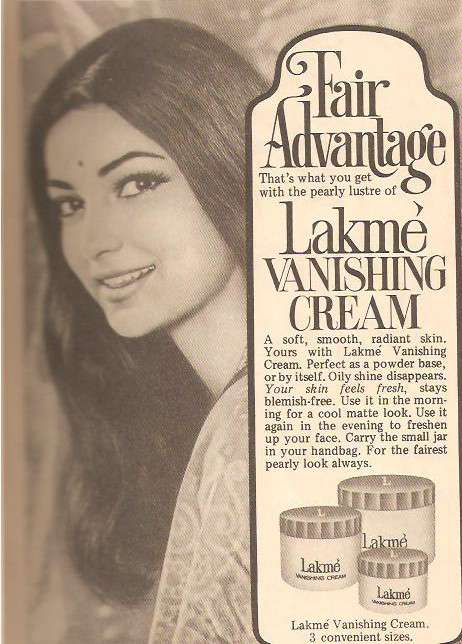

Tata (born to an Indian father & French mother in Paris) founded Lakmé in collaboration with the French companies Robert Piguet and Renoir. It so happened that the Opera was playing in Paris at the time, and a member of the Renoir team put forth the suggestion to name the cosmetic line after the Opera.

The name combined Indian tradition and culture with “western modernity” and had a French touch. Moreover, it was named after the Goddess of wealth & beauty. It was likely to resonate with women who were used to buying ‘foreign made’ cosmetics.

The genesis of India’s Lakmé

India with a rising social mobility was no longer the same as the one presented in 19th century Operas. This culminated in a visionary Prime Minister and an entrepreneur born to Indian-French parents, together creating a different image of India.

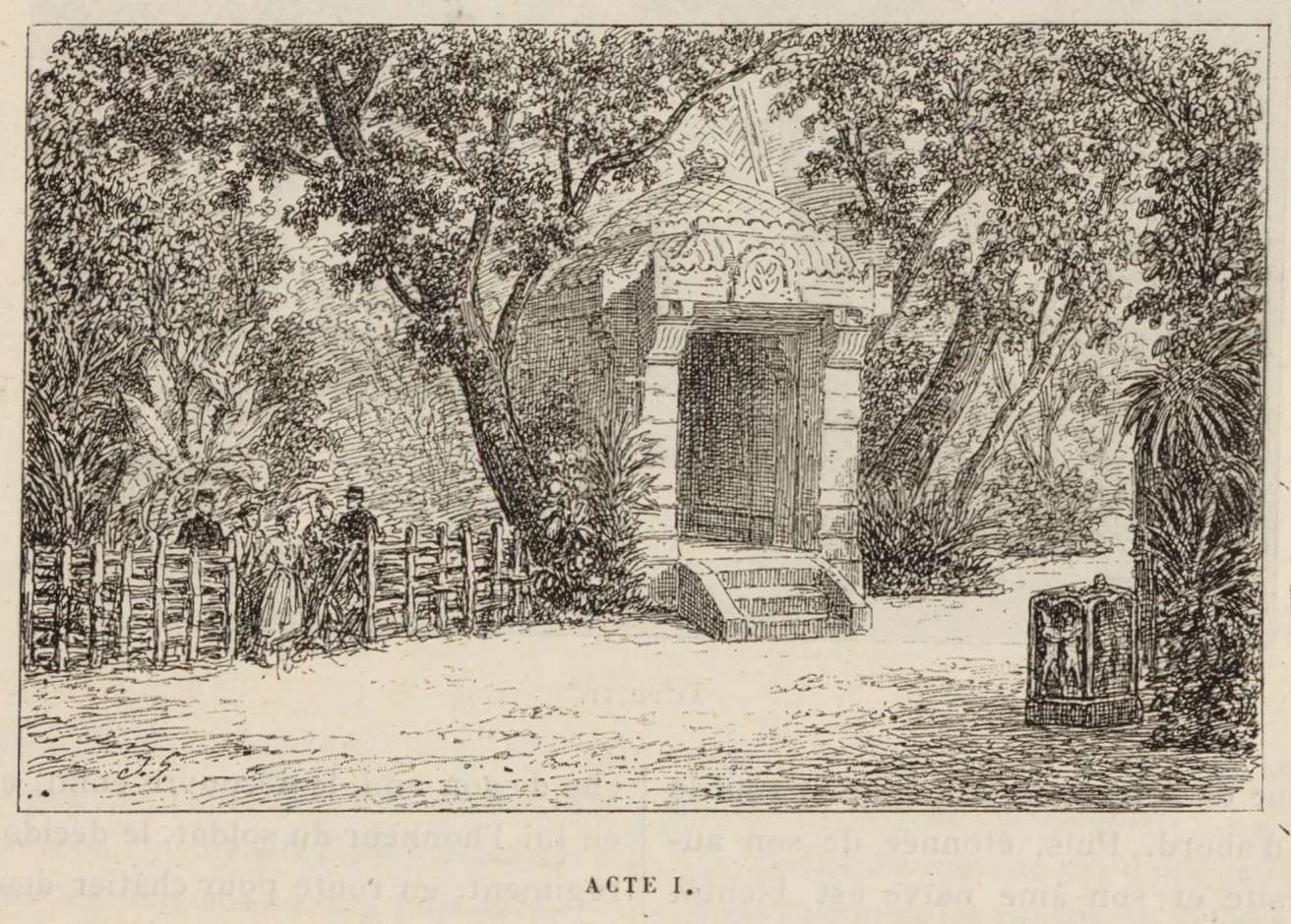

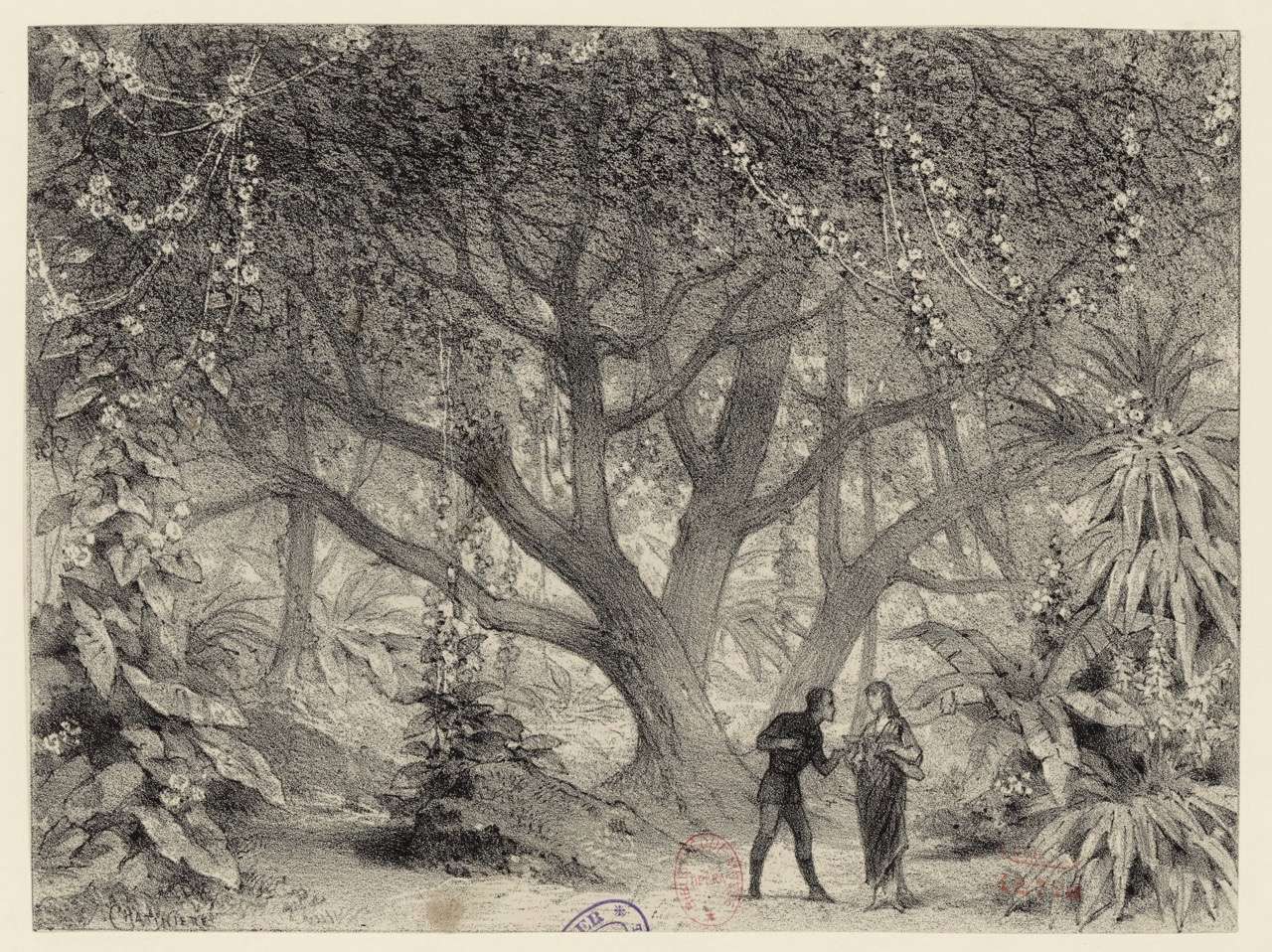

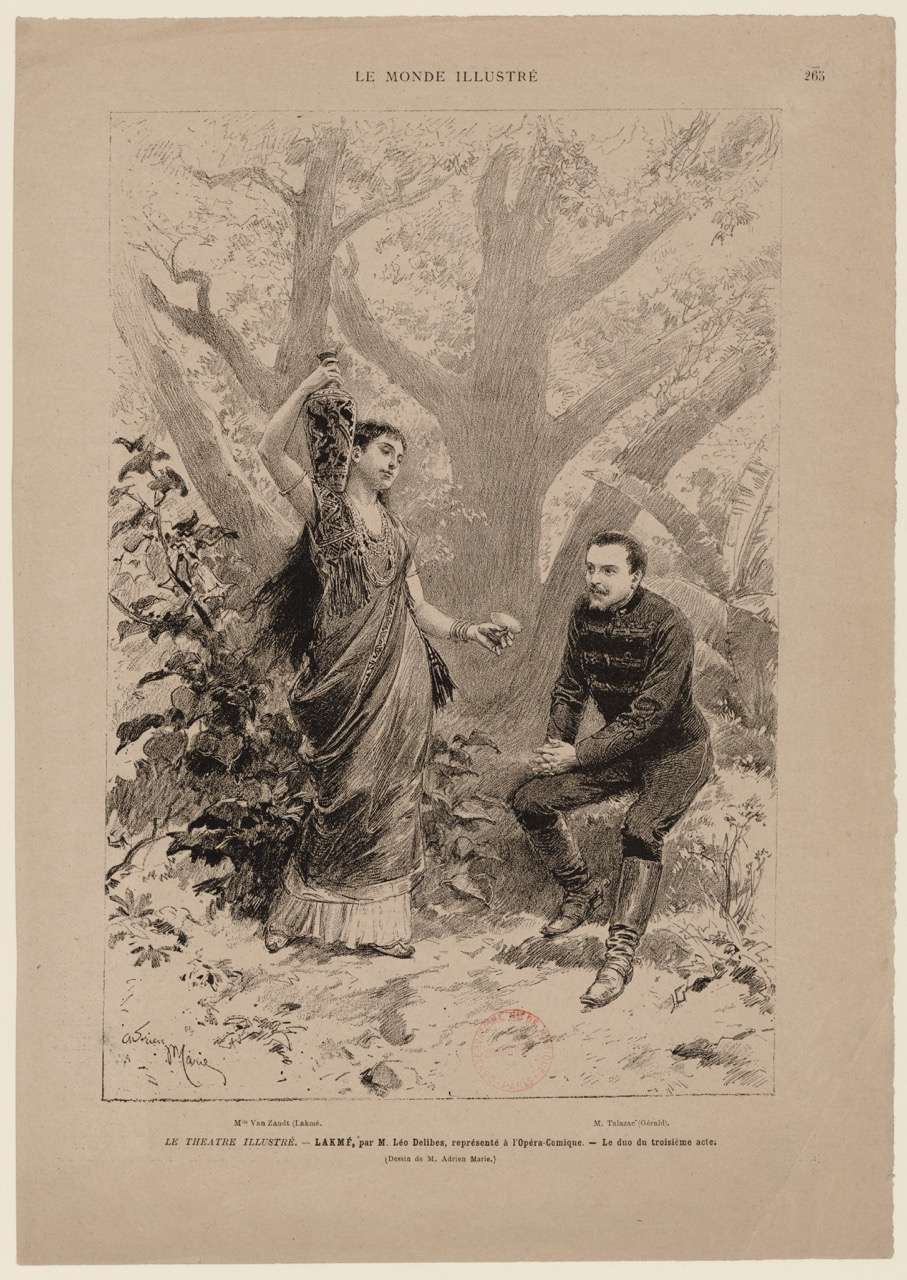

In Pictures: Lakmé, the Opera

Act I: the Brahmin Nilkantha hopes for the “oppressors” (British) to perish. Meanwhile, two soldiers and their female companions trespass into his ashram when he is away.

Act II: Lakmé and Gerald meet and fall in love while the latter is making sketches of the jewellery she left aside while bathing. This incident enrages Nilkantha.

Act III: Nilkantha persuades his daughter Lakmé to sing in the market square, hoping to attract Gerald.

Act IV: Nilkantha’s plan works. Gerald hears Lakme singing and approaches her. Nilkantha then takes the opportunity to stab Gerald with an intention to kill him. Gerald however is only wounded & the couple run into the forest with assistance from Nilkantha’s aide. Here Lakmé nurses him to health.

Act V: Lakmé hears of sacred spring in the forest with magical properties. Drinking the water of the spring can unite people in love, and so she heads in search of it. While she is away, Gerald is reminded of his military duties towards the Empire.

Act VI: On her return, Lakme senses Gerald’s withdrawal & in despair kills herself by consuming the poisonous datura flower. Gerald however, drinks from the sacred water.

souk picks

souk picks