To give you (and us) a break from weighty Big Stories, we put together a fun romp through the history of the ‘Super Bowl of fashion’—which has more cultural relevance today than the Oscars. Feel free to skip ahead to Headlines That Matter for hard news:)

Researched by: Rachel John & Anannya Parekh

First, a bit of history…

Contrary to what its name suggests, the Met Gala is all about a single department of the Metropolitan Museum called The Costume Institute—which is where it all started.

Origin story: In 1937, theatre luminary Irene Lewisohn founded the Museum of Costume Art. In 1946—with the financial support of the fashion industry—it merged with the Metropolitan Museum of Art—and was renamed as The Costume Institute. Today, it has a collection of more than 33,000 objects—from the fifteenth century to the present.

The institute is the only Met department that has to fund its own operations. Hence, in 1948, fashion publicist Eleanor Lambert—who also launched New York Fashion Week—began holding an annual midnight supper to raise money for it. It was essentially an event for New York’s high society—held at upscale venues like the Waldorf Astoria hotel—not the museum.

From society party to gala: The event became a far grander affair—with lavish displays and A-list celebrities—with the arrival of former Vogue editor Diana Vreeland. She is also the person who introduced the idea of having a different theme each year. The party venue was also shifted to the museum—where it remains to this day. Vreeland’s very first exhibit ‘The World of Balenciaga’ was a blockbuster hit. See one of the displays below:

Also see this exhibit from ‘Romantic and Glamorous Hollywood Design’ held in 1974:

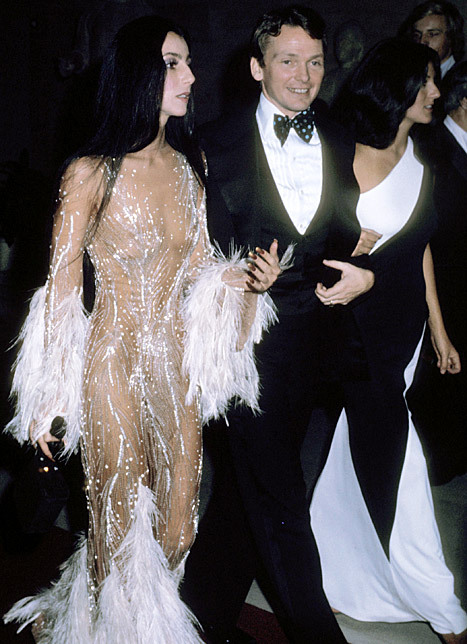

FYI: Kim Kardashian isn’t a patch on Cher in her heydays. Here she is at the Met in 1974:

Quote to note: Vreeland helped transform the world of costume—liberating it from of the tiny confines of Manhattan socialites:

Quote to note: Vreeland helped transform the world of costume—liberating it from of the tiny confines of Manhattan socialites:

Until the spring of 1973, it could be said that the field of costume had been a sleepy and rarified one, at least in the context of museums. An aura of antiquarianism seemed to enshroud every costume display, and they had, for all intents and purposes, no audience beyond a few specialists… Thanks to her individual achievements, there is now broad public awareness of costume. How many people are there who can actually be credited with having transformed an entire field? Diana Vreeland did that with éclat and with an uncanny sense for drama and style.

The Anna Wintour years: In 1999, the Vogue editor took over as chairperson of the benefit—bringing in the power and resources of the magazine to the gala. The event has since skyrocketed into an unparalleled cultural event—growing ever more lavish each year. The gala also helped cement Vogue’s position as the most powerful voice in fashion. More importantly, it has made Wintour the gatekeeper of fame—deciding who is ‘in’ or ‘out’:

Wintour…turned it into an event that had representatives for celebrities calling and asking for invitations. Many were repeatedly denied. The celebrity guest list, carefully curated over the years by Wintour, led the Met Gala to be dubbed the “Oscars of the East Coast,” but that moniker no longer fits: in terms of the red carpet, the Met Gala now surpasses the cultural significance of the Oscars.

From gala to ‘costume party’: Where Vreeland had a theme for the exhibit, Wintour turned it into an iron-clad dress code for the guests—forcing celebrities into ever more inventive interpretations of the year’s theme. Designer Tom Ford complains:

The only thing about the Met that I wish hadn’t happened is that it’s turned into a costume party. That used to just be very chic people wearing very beautiful clothes going to an exhibition about the 18th century. You didn’t have to look like the 18th century, you didn’t have to dress like a hamburger, you didn’t have to arrive in a van where you were standing up because you couldn’t sit down because you wore a chandelier.

OTOH, the pressure to be outrageous has also given the Met Gala the element of surprise and whimsy missing on other red carpets. Our favourite on-point Wintour anecdote:

When Kim Kardashian wore a custom latex Thierry Mugler dress that redefined tight to the camp-themed party in 2019, Wintour kept saying to Lisa Love, a personal friend and former longtime West Coast director of Vogue, “Can you please tell her to sit down?” Love had to explain that, actually, Kardashian physically could not sit.

You can see why, lol:

The Met Gala: Fashion or art?

The two worlds have long inspired each other. Back in 1937, Salvador Dali hand-painted a lobster onto a Elsa Schiaparelli dress:

In 1965, Yves St Laurent paid homage to Dutch artist Piet Mondrian with A-line dresses that were “divided by black lines into white and primary-colored squares”:

But these collaborations were mostly about fashion taking superficial inspiration from artists. And despite the Met Gala’s popularity, the uppity world of fine art kept the crassly commercial fashion industry at arm’s length. For instance, a Giorgio Armani exhibit at the Guggenheim Museum in 2000 sparked backlash—perhaps also because Armani gave a multi-million dollar donation just months before it was unveiled.

But these collaborations were mostly about fashion taking superficial inspiration from artists. And despite the Met Gala’s popularity, the uppity world of fine art kept the crassly commercial fashion industry at arm’s length. For instance, a Giorgio Armani exhibit at the Guggenheim Museum in 2000 sparked backlash—perhaps also because Armani gave a multi-million dollar donation just months before it was unveiled.

Fashion as art: Today, however, fashion has acquired the status of art—no longer dismissed as a ‘women’s thing’. One reason is that the biggest names in the business now want to be ‘cultural brands’:

Fashion houses now look to transcend their narrow identification with clothing and accessories. Louis Vuitton… is “much more than a fashion brand. It’s a cultural brand with a global audience.” By emphasising its links to art — and, by implication, art’s rarity and exclusivity — Louis Vuitton symbolically undercuts the reality that its business imperative (to sell more goods) effectively decreases the rarity and exclusivity of its products… as a “cultural brand,” Louis Vuitton dissolves the crass reality of products and sales in the mythic allure of storytelling and image.

Hence, it’s collaboration with Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama:

‘Fashionable’ art that sells: In turn, the high fashion industry has thrown a financial lifeline to struggling museums—giving them a lucrative form of revenue. The Met’s collab with luxury brands goes far beyond an annual Met Gala:

‘Fashionable’ art that sells: In turn, the high fashion industry has thrown a financial lifeline to struggling museums—giving them a lucrative form of revenue. The Met’s collab with luxury brands goes far beyond an annual Met Gala:

In the last three years, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, for example, fashion designers like Dior have sponsored shows devoted to their work. When the museum held a show of Gianni Versace's fashions, it was paid for in part by Conde Nast, publisher of fashion magazines like Vogue that depend on Versace for advertising. Next year the museum hopes Chanel will finance a show of its work. Tiffany, Faberge and Cartier also paid for shows about their products.

Quote to note: As Natasha Degen writes in the New York Times, we are witnessing an unprecedented convergence of art and fashion—which has proved extremely profitable for both:

The confluence of art and fashion at the Met Gala and elsewhere has far-reaching ramifications. Each field has begun to see itself anew. Art, having never achieved such mass relevance, wonders whether it might descend from its ivory tower and become genuinely popular. Fashion, unused to such high-culture cred, wonders if it might win new seriousness and cachet in the public eye. Inspired by these potentials, each side turns more ardently to the promise implicit in the other.

The problem with codependency: But cultural relevance is a double-edged sword—which became painfully apparent this year when the gala decided to pay tribute to Karl Lagerfeld. The iconic Chanel designer is also a well-documented misogynist and racist. For example, when asked about sexual harassment in the industry, he infamously said: “If you don’t want your pants pulled about, don’t become a model! Join a nunnery, there’ll always be a place for you in the convent.” Also this: “The hole in social security, it’s also [due to] all the diseases caught by people who are too fat.”

Lagerfeld’s choice likely reflected the fact that he was a close friend of Wintour—and came with guaranteed sponsorship from Chanel. And the firestorm of criticism did little to blunt the success of the event. But fashion experts say it points to the delicate “balancing act of commercial interests and values (or at least the performance of them).” And that holds doubly true for museums which make even more self-righteous claims to cultural and moral value.

Point to note: Back in 2015, the Met Gala’s theme was ‘China: Through the Looking Glass’—which opened the door to all sorts of offensive cultural appropriation. It is difficult to imagine either the Met or Wintour getting away with it today. Or Sara Jessica Parker, for that matter (wtf is that?):

The bottomline: The Met Gala is no longer a glorious celebration of either art or fashion. It’s a grand pop culture feast that celebrates everything that is ‘it’—the thing that matters right here, right now—be it a YouTube influencer or politician or a brand. Kinda like Alia Bhat:

Reading list

For the history of the gala, we recommend checking out Architectural Digest and Artsy. TIME is great on the influence of Wintour. For the confluence of art and fashion, read this New York Times op-ed and reported piece on museum collabs with brands. For a good non-paywalled read: check out this older Vox piece. Washington Post has more on the history of the relationship between art and fashion. Variety has more on how the gala has become a moneymaker for Conde Nast.

souk picks

souk picks