Editor’s Note: This is the quaint and often amusing history of ice houses built by colonial burra sahibs desperate for a chilled chota peg in the soaring heat of Indian summer. The piece is republished from The Heritage Lab—a wonderful resource of stories on cultural heritage, art, museums and lots more. You can find other lovely essays on art and culture over at their website.

Ice in British India: The art of keeping cool

“Now khus khus tatties (mats) fail to cool

And punkah breeze defying

The mercury marks 95

And we are almost frying…”

This poem could well have been composed in today’s time.

Indian summers have always been notoriously difficult, but unlike the 1830s when this poem was published, today, we do have easy access to cooled water.

Chilled water is somewhat of a necessity for many of us today. But in the 15th century, chilled drinks were a luxury available only to the royals. The British, even as they tried to emulate the Mughals, were unable to afford the Rs 1 per pound ice from the Himalayas. And so, they resorted to manufacturing ice in the plains. The process, as described by Fanny Parkes (the 18th-century travel writer) was labour-intensive.

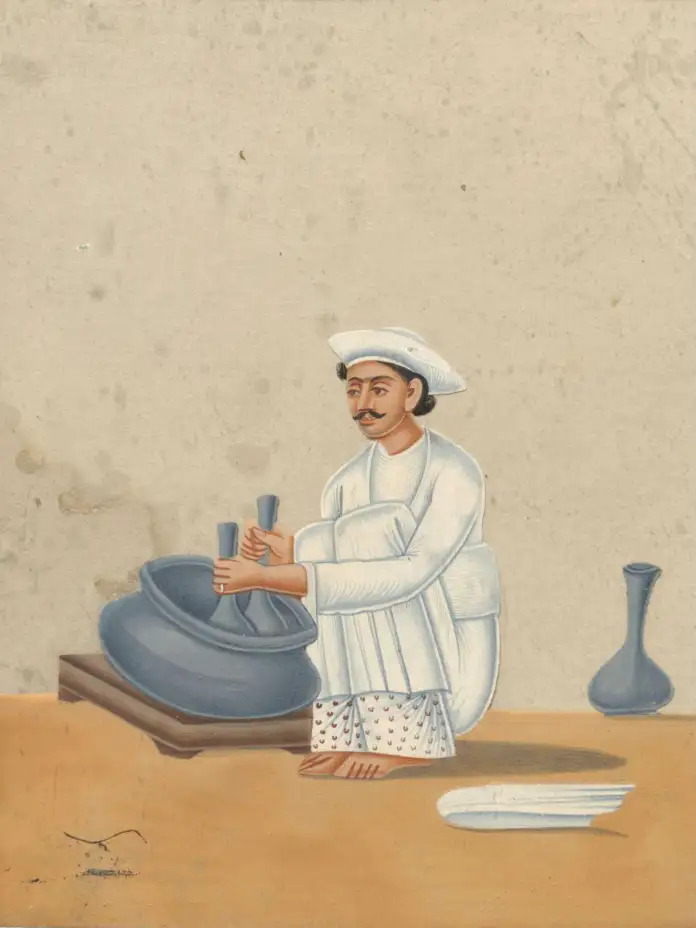

Ice—in a slushy form—was thus made available to the administrative elite in colonial India. Here’s a painting of an Abdar—this indispensable domestic worker in the summers was usually employed by British officers to keep their drinks cool.

Ice—in a slushy form—was thus made available to the administrative elite in colonial India. Here’s a painting of an Abdar—this indispensable domestic worker in the summers was usually employed by British officers to keep their drinks cool.

But in case you’re wondering, this technique produced nothing like the ice we know today.

But in case you’re wondering, this technique produced nothing like the ice we know today.

Ice, as we know it, came to India in 1833. While the British in India were desperately seeking ways to beat the summer heat (hanging wet khus on window openings, hiring punkhawalas, getting away to a hill station), far away in Cuba, a young man, unable to get a chilled drink, thought of an idea.

In 1805, when Frederic Tudor came up with the idea of exporting ice to the tropics, everyone laughed at him.

By the 1860s, Tudor had amassed a fortune of millions and has been famous since then as the “Ice King”.

By the 1860s, Tudor had amassed a fortune of millions and has been famous since then as the “Ice King”.

On 12 May, 1833, Tudor dispatched a shipment of ice to India. After sailing 4 months and passing through the Equator twice, the ship carrying 180 tons of ice reached India—but only with about 100 tons of ice. Still, the ice that arrived instantly uplifted moods.

Frederic Tudor’s biggest challenge was preserving the ice. During the journey to India, Tudor insulated the cargo hold with a mixture of straw, bark, and sawdust, so most of the ice survived the journey.

Frederic Tudor’s biggest challenge was preserving the ice. During the journey to India, Tudor insulated the cargo hold with a mixture of straw, bark, and sawdust, so most of the ice survived the journey.

The people of Calcutta, jubilant at the thought of having ice all year round (at a reasonable price), offered to build an Ice House through crowdsourced funding.

In his essay, ‘The Nineteenth-Century Indo-American Ice Trade’, David G. Dickason reproduces a poem that originally appeared in The Englishman in 1837.

Now kus kus tatties fail to cool

And punkah breeze defying

The mercury marks 95

And we are almost frying.

Still, some relief we may enjoy,

For with our "dall' and rice, Sir,

Liquids become a luxury

From Yankee Tudor's Ice, Sir.

This blessing answers very well,

For sundry other uses

One, as a friend to you I'll tell,

To Comfort it reduces.

Send for a spon (choose a light brown)

At Bathgate's you can get it,

Make a large wig to fit your crown

And with Ice water wet it.

In Calcutta, Indian businessmen such as Dwarkanath Tagore were part of the committee trying to fund the initiative to ensure a regular supply of ice in the city. The Ice House was located at Hare Street next to the Metcalfe House. By 1836, 12,000 tons of ice had been shipped to Calcutta and 10 years later, this figure had spiralled to 65,000 tons. Soon, the popularity of American ice reached the other port-cities of India — Bombay and Madras.

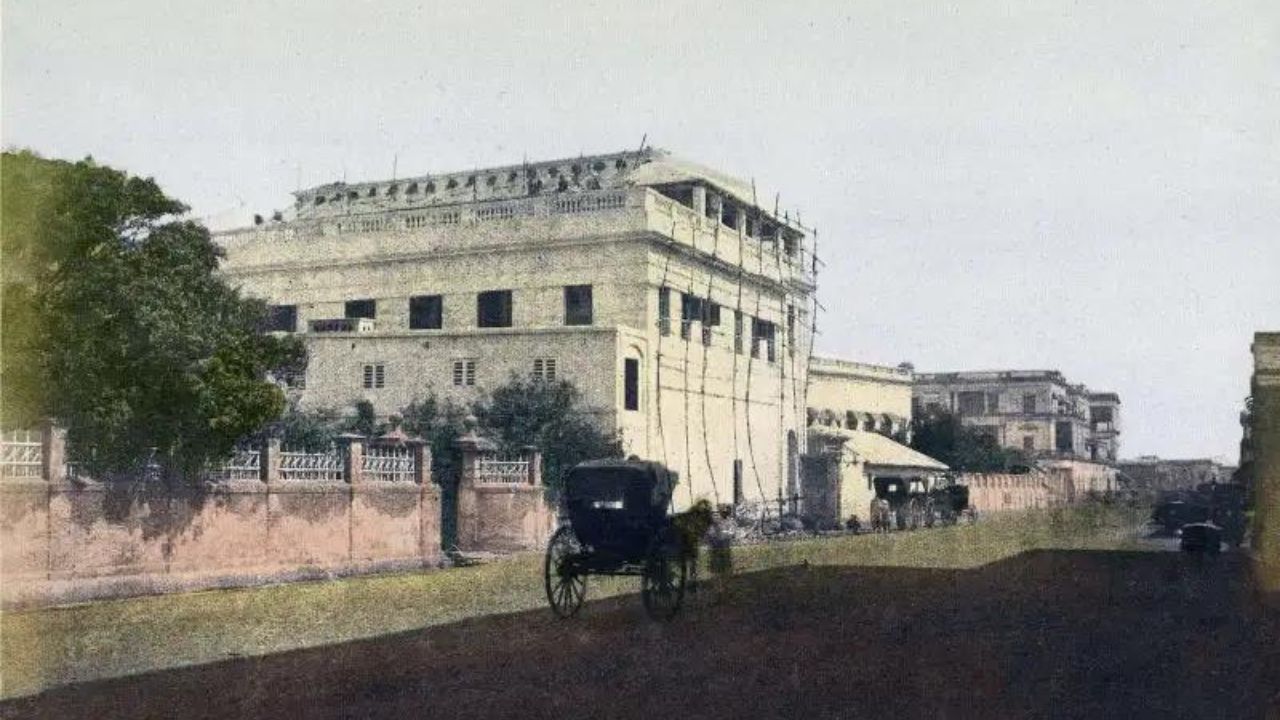

The city of Bombay received its first ice cargo in September 1834. The city had an advantage of being the first destination for ships coming in from Boston. This called for Bombay's first Ice House, which was built through subscription funds raised by Bombay Times & Journal of Commerce (later TOI). They crowdsourced nearly Rs 3,900 to build the Ice House which was erected by 1843. In Bombay, ice sold for 4 annas (25 paise) per pound.

The city of Bombay received its first ice cargo in September 1834. The city had an advantage of being the first destination for ships coming in from Boston. This called for Bombay's first Ice House, which was built through subscription funds raised by Bombay Times & Journal of Commerce (later TOI). They crowdsourced nearly Rs 3,900 to build the Ice House which was erected by 1843. In Bombay, ice sold for 4 annas (25 paise) per pound.

Meanwhile in Madras, an Ice House was erected in 1841-2.

David G. Dickason points out the numerous customs and business subsidies Tudor received from India’s British rulers. For example, in Madras, ice was a duty-free item, joining the ranks of pearls and precious stones. Here, Tudor even received a 20-year lease on the Ice House starting 1845!

David G. Dickason points out the numerous customs and business subsidies Tudor received from India’s British rulers. For example, in Madras, ice was a duty-free item, joining the ranks of pearls and precious stones. Here, Tudor even received a 20-year lease on the Ice House starting 1845!

In 1874, entrepreneurs in Madras manufactured ice locally using a steam processor at the International Ice Company—spelling the end of Tudor’s ice exports to the city. The Ice-House was acquired by the Government of Madras and it stands at the same spot, remodelled as the Vivekananda House.

From Madras, the idea spread to Calcutta. The Bengal Ice Company, the second artificial ice maker in India, was formed in 1878. The Calcutta Ice House was demolished in 1882; the one in Bombay was demolished in the 1920s.

What remains with us though, is Tudor’s story—the man who despite his early failures— never gave up.

What remains with us though, is Tudor’s story—the man who despite his early failures— never gave up.

He who gives back at the first repulse and without striking the second blow,

despairs of success – has never been, is not, and never will be a hero in war, love, or business.

- Frederic Tudor ( first page of Tudor’s’ “Ice House Diary” )

souk picks

souk picks