Due to rising sea levels, five island nations are likely to disappear. How do they plan to deal with their looming extinction?

Editor’s note: This is the second part of a two-part series on rising sea levels. The first part looked at the big global picture—and which parts of India will be affected.

First, the fate of island nations

Where we are: Most scientists agree that even if we take steps today to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, average sea levels around the world will still rise by up to 6.5 feet (1.98 metres) by the end of the century. This means coastal areas around the world will be in great jeopardy.

But islands in the Pacific Ocean are even more vulnerable. While the global average rise in sea level is 3.2 millimetres per year, parts of the western Pacific are seeing an average jump of 8-12 millimetres—due to wind patterns that move more water to the region. It is likely that five nations—the Maldives, Tuvalu, the Marshall Islands, Nauru and Kiribati—will become uninhabitable by 2100—creating 600,000 stateless climate refugees.

Point to note: Small islands have already been swallowed by the waters around the world—from Hawaii to Japan and the Arctic coast. Luckily, they were uninhabited. You can see photos of the Hawaiian island before and after a giant hurricane:

Vanishing islands: Scientists expect oceans will rise by nearly a metre (39 inches) around the Pacific and Indian Ocean islands by the end of the century. Now the highest part of even the smallest islands among these nations will most likely remain above sea level. But it does not mean they will remain livable, and here’s why:

Vanishing islands: Scientists expect oceans will rise by nearly a metre (39 inches) around the Pacific and Indian Ocean islands by the end of the century. Now the highest part of even the smallest islands among these nations will most likely remain above sea level. But it does not mean they will remain livable, and here’s why:

One: Coastlines naturally erode and rebuild themselves. But climate change is also creating more extreme weather—more intense and frequent storms that disrupt this cycle. On most islands, their most critical infrastructure is on the coast—which will be the first to disappear. This means ports, airports, primary roads, power plants and water treatment plants.

Two: Frequent tidal flooding has already made the soil salty—and unsuitable for any kind of farming. Many of these island nations already have to import what used to be staple local crops. And the salt water has also contaminated groundwater supplies—while global warming brings more droughts. The result is painfully evident in places like Tuvalu:

Tuvalu is now totally reliant on rainwater, and droughts are occurring with alarming frequency. Even if the locals could plant successfully, there is now not enough rain to keep even simple kitchen gardens alive. The Frank family spend around AU$200 (£105) a fortnight on groceries, a bill that keeps rising as the fruit on the trees that ring their modest home – breadfruit, bananas and pandanus – fail to ripen, and fall to the sandy ground, inedible and rotten.

Data point to note: Pacific island nations account for just 0.03% of global emissions.

Surviving the great wipeout: The case of Tuvalu

The Polynesian nation is a tiny archipelago in the Pacific Ocean—somewhere between Hawaii and Australia. Tuvalu’s total land area accounts for less than 26 square kilometres—and it is home to 11,000 people. Most of the islands are barely three metres above sea level. The largest island Fongfalee stretches just 20 metres across at its narrowest point.There’s nowhere to run when things get bad. You can see where it’s located below:

How bad is it? Tuvalu is expected to be the first nation lost to climate change. Already, two of its nine islands are on the verge of going under. And its fate appears to be sealed:

How bad is it? Tuvalu is expected to be the first nation lost to climate change. Already, two of its nine islands are on the verge of going under. And its fate appears to be sealed:

At current rates of sea level rise, some estimates suggest that half the land area of the capital, Funafuti, will be flooded by tidal waters within three decades. By 2100, 95% of land will be flooded by periodic king tides, making it essentially uninhabitable.

The question of territory: What will happen to Tuvalu when most of its islands disappear—and there’s nothing left but a patch of ocean? A nation state is defined under international law by the Montevideo Convention and has four criteria: a permanent population, a defined territory, a government and the capacity to enter into relations with other states. What happens if there is no territory—and no permanent population? Around 20% of the residents have already moved to New Zealand—under a program that allows 150 citizens to be granted residence every year. So how will a country like Tuvalu survive?

Raise the islands: Many citizens are determined to stay: “As Tuvaluans, we have to stay here and protect our country, because if we save Tuvalu, we also save the world.” And the government is doing its best to reclaim the land—as part of a project called the L-TAP or “Te Lafiga o Tuvalu” (Tuvalu’s Refuge) Project. The plan: “Suck sand” from the lagoon to raise the elevation of areas within the island. The aim is to reclaim 3.6 square kilometres (1.4 square miles) from the lagoon—which would more than double the size of the most populated island—and link it to two smaller islets:

The vision: 3.6 sq km of raised, safe land with staged relocation of people and infrastructure over time; a sustainable water supply; greater food and energy security; and space for expanding civic and commercial areas, including government offices, schools and hospitals.

Of course, all this requires money—estimated price tag was $300 million in 2019. And that is why Tuvalu and other Pacific Island nations are the loudest voices demanding climate change reparations—compensation from wealthy countries who bear the greatest responsibility for their plight.

Relocate Tuvalu: Last year, Tuvalu and its neighbours launched the Rising Nations initiative. The aim: to ensure their nations will endure even after their land disappears. They’ve asked the UN to craft a legal framework that recognises their sovereignty “even if we are submerged underwater, because that is our identity." And they want a global settlement that includes relocation:

This settlement includes, ultimately, our relocation elsewhere in the world where our peoples will be welcomed and celebrated. Our peoples will expect to maintain their sovereignty and citizenship, preserve our heritage, and be educated in our language and traditions. We do not seek to be a burden on others; equally, natural justice dictates that we are not fobbed off with a wasteland.

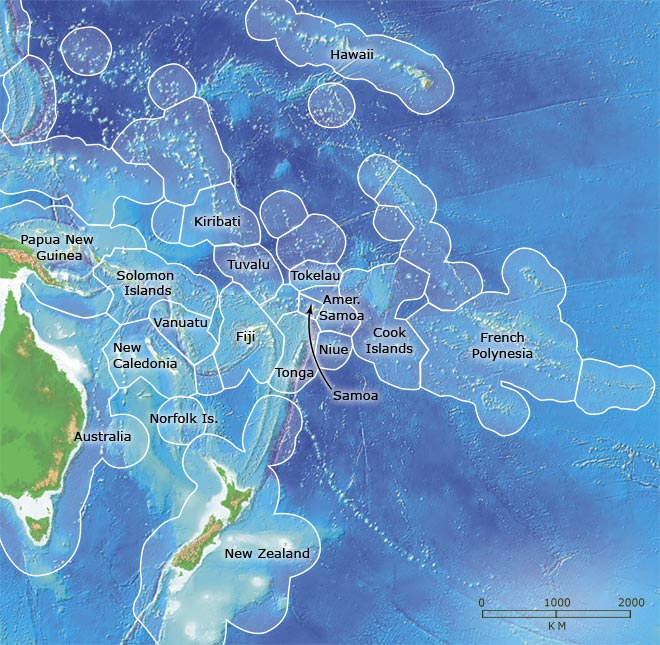

Where’s the money? All coastal nations have an exclusive economic zone that extends 200 nautical miles from the shore. Here’s a map of the Pacific Island EEZs:

With 33 islands scattered over 3.5 million square kilometres, Kiribati has one of the largest exclusive economic zones (EEZs) in the world. Once their sovereignty is secure, they will continue to control all fishing and mining rights even after the islands disappear. These, in turn, will finance their new government and home—wherever it may be in the world.

With 33 islands scattered over 3.5 million square kilometres, Kiribati has one of the largest exclusive economic zones (EEZs) in the world. Once their sovereignty is secure, they will continue to control all fishing and mining rights even after the islands disappear. These, in turn, will finance their new government and home—wherever it may be in the world.

Point to note: Australia offered land in exchange for these rights—which Tuvalu rejected as “imperial thinking.”

Tuvalu’s digital twin: At the UN Climate Change conference in 2022, Justice Minister Simon Kofe announced his country’s plan to create a “digital twin” of Tuvalu. Here’s how it will work. The government will become virtual—all data will be stored on the cloud, services and administration will go online, as will elections. Tuvalu will also create a replica of itself in the metaverse—which will be run by this virtual government. This digital Tuvalu will do the following:

- It will recreate an immersive and interactive version of the islands—so its citizens around the world can “live” in it.

- They will also be able to interact with each other—and preserve their language, norms and customs.

- And this digital Tuvalu will have sovereignty, exercising control over its virtual land—and maritime rights of its waters in the real world.

But, but, but: As Brown Political Review points out, sovereignty in the virtual world is tricky:

[V]irtual Tuvalu will fully rely on Meta, an American corporation. If Meta stops operating for any reason, Tuvalu will vanish. Can a country with such a reliance on a single US corporation be considered a sovereign state? Even if Tuvalu creates its digital twin independently of Meta, it would still need to create data centres for the virtual platform on another nation’s land.

The bottomline: Digital Tuvalu remains Plan B for now. The government and its people are determined to do their best to save their islands. The real problem: the rest of the world has to get their act together to make it happen. Wealthier countries show no signs of reducing their emissions—or ponying up the cash to save the islands they have doomed to extinction.

Reading list

The Guardian has an excellent ground report from Tuvalu. NBC News and The Hindu offer the big picture on the future of the Pacific Islands. As for the metaverse plans, read the Verdict, Mashable and The Guardian. The Conversation and Brown Political Review look at the issue of sovereignty.

souk picks

souk picks