The numbers of birds are declining around the world—and India is no exception as the dismal ‘State of India’s Birds’ report reveals

Researched by: Nirmal Bhansali & Aarthi Ramnath

First, some background

There are 10,000 species of birds that have been found across the world. Of these, 1,350 have been seen in India. And 72 of these birds are endemic to India—as in, they can only be found in certain parts of the country. Example: the white-bellied blue flycatcher that lives in the Western Ghats:

Or the Great Indian Bustard of Rajasthan:

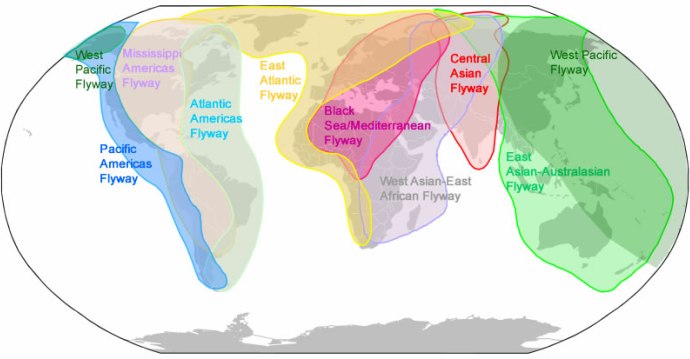

Migratory species: The count of Indian species includes visitors—i.e the 400 species of migratory birds that come to India for parts of the year. They account for 30% of the total birds in India—and enter the country along three key routes: Central Asian Flyway, East Asian-Australasian Flyway and Asian-East African Flyway. See the map below:

This is another visualisation of the routes:

The most popular route: is the Central Asian Flyway that connects India to the Arctic Circle. It accounts for 80% of the birds that visit our country. These include the famous flamingos that travel from Iran, Pakistan and even Israel to Mumbai and Gujarat.

Point to note: The estimates of migratory birds are rough since they are difficult to track. The most popular method is ringing them with unique codes. But the number of ring recoveries is very low: “Unless a ringed bird is captured at another site, we get no information regarding its movements. Thus for most species, we still do not have data on migration routes and breeding ranges.”

The state of Indian birds

The backstory: The first State of India’s Birds report was published in 2020—and involved a collaboration between ornithologists affiliated with ten Indian research and conservation organisations. It is one of the most rigorous and innovative projects to assess the bird population in India. The report makes use of a crowdsourced program known as eBird:

Managed by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology eBird began with a simple idea — that every birdwatcher has unique knowledge and experience. It gathers this information in the form of checklists of birds, archives and curates it, and shares it freely to power new data-driven approaches to science, conservation and education. Currently, eBird is the world’s largest biodiversity-related citizen science project, with more than 100 million bird sightings contributed each year by eBirders around the world.

Indian birdwatchers have been documenting sightings on eBird since 2014.

The 2023 report: The report is based on 30 million observations contributed by more than 30,000 birdwatchers across the country. It has information on 942 species—and has a whole host of red flags.

One: It labels 178 bird species as “High Priority”—as in, they require immediate conservation action. This number has jumped by 104 since 2020. An example: the migratory Ruddy shelduck or Brahminy duck—that visits Chandigarh in the winters:

Two: There was enough data to assess the long term trends—over 30 years—for 338 species. Of these, 60% are declining in numbers—and at least 98 suffered rapid declines. And 359 species assessed for annual change over the past eight years, 40% are in decline.

Three: Certain kinds of species are disappearing rapidly. Example: Birds that feed on vertebrates and carrion—including raptors and vultures. This is especially true of raptors that rely on specific habitats such as the Short-toed snake eagle:

Large numbers of wetland birds like the dainty curlew sandpiper have disappeared from Point Calimere Tamil Nadu and Pulicat Lake in Andhra Pradesh.

FYI: Pulicat is under threat from a nearby Adani-run port—which has sparked local protests.

Four: The fall in migratory birds is precipitous. The numbers have fallen by 50%—and there has been an 80% decline in those that breed in the Arctic:

Migratory birds are facing decline due to several reasons including the dangers faced during migration, extreme weather events, starvation, and hunting/illegal killing. Migratory birds that breed in the Arctic are facing the most serious impacts of climate change, for example.

A worrying mystery: The report notes that birds endemic to Western Ghats and Sri Lanka biodiversity hotspots have rapidly disappeared over the past 20 years—but the reasons are not clear.

The good news: A number of species such as the feral Rock Pigeon, Ashy Prinia, Asian Koel and Indian Peafowl are thriving:

In the last 20 years, Indian Peafowl has expanded into the high Himalaya and the rainforests of the Western Ghats. It now occurs in every district in Kerala, a state where it was once extremely rare. Apart from expanding its range, it also appears to be increasing in population density in areas where it occurred earlier.

And the numbers of others such as the Baya Weaver and Pied Bushchat are also stable. See the Peafowl below:

Point to note: Just because the numbers are declining in India, it does not mean that all these species are vulnerable at the global level. For example, the Short-toed snake eagle is listed as of ‘least concern’ by the International Union for Conservation of Nature—as it is found in vast parts of Africa, Europe and Asia. Ninety species listed as High Priority species in India are classified as of Least Concern by the IUCN.

The very unsurprising causes

The report notes all the usual causes for the dwindling numbers—urbanisation, habitat loss, pollution, climate change etc. etc. But here is a specific example that brings it home: urban ponds. Around 170 species live near Delhi’s ponds—around 37% of all species. A number of them—like the bar-tailed godwits—are migratory birds. But here’s the number to blow your mind: ponds only account for 0.5% of Delhi’s geographical area. And yet we have not been able to protect these precious habitats. The number of waterbodies in Delhi has dropped from 1,000 in 1997 to 700 in 2022—all due to “encroachment.”

Another illuminating example: Vultures. They have nearly disappeared—primarily due to a single farming practice:

In the 1980s, India had an estimated four crore vultures. By the late 1990s, 99% of the vulture population had been wiped out due to a non-steroid anti-inflammatory drug that was administered on cattle as a painkiller.

Vultures fed on the cattle—ingested the painkiller—which destroyed their kidneys. But here’s the astonishing bit:

[T]he decline in the population of vultures led to an alarming increase in the population of stray dogs, especially in urban areas across India. It quoted a study that found that this abrupt increase in the stray dog population resulted in high rates of rabies incidences costing the country about Rs 34 billion between 1993-2006.

This link between the decline of vultures and the increase of feral dogs is a global trend—holding true even in places like Ethiopia.

The bottomline: When a bird species disappears, we’re losing a whole lot more than just that bird.

Reading list

The Wire has the most details on the report—but Hindustan Times and The Statesman have highlights. We highly recommend this older Scroll deep dive that offers the big picture on bird conservation in India. For more on Delhi ponds, read Mongabay on why they matter and The Hindu for why they are disappearing. The Print has more on vultures in India—while Science Daily looks at the link to feral dogs.

souk picks

souk picks