Global maritime organisations, environmentalists and even shipping companies are pushing to move a key shipping lane by 15 nautical miles (27 kilometres). The reason: the high traffic poses a serious danger to blue whales. But Sri Lanka is stoutly resisting any attempt to do so—calling it a conspiracy to undermine its ports.

Researched by: Rachel John & Aarthi Ramnath

Wait, what’s happening with whales?

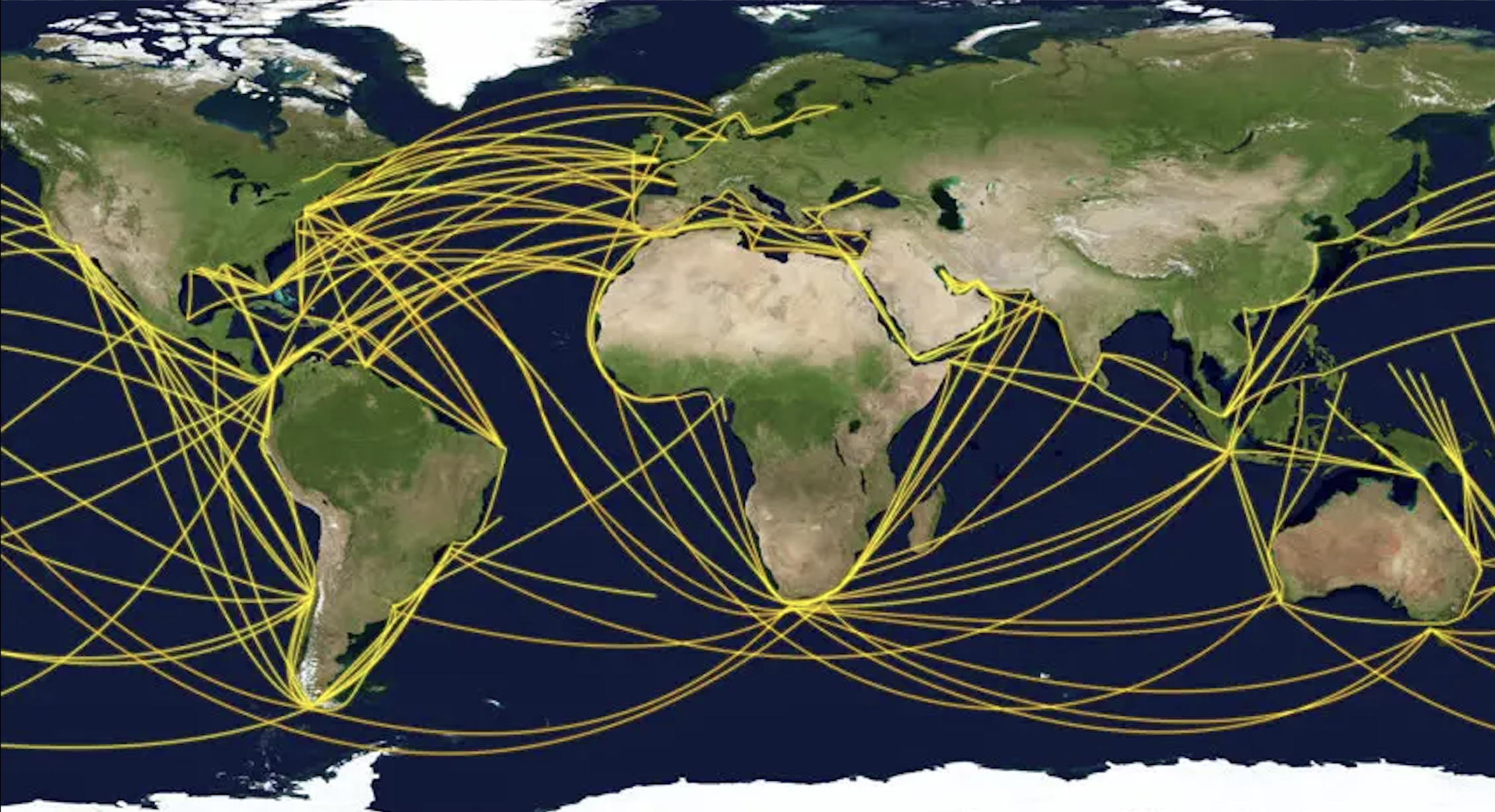

Once upon a time, hunting was the only hazard humans posed to whales. By the 1980s, whale hunting was mostly banned but the marine animals soon faced a far greater danger: shipping lanes. These sea routes deliver 11 billion tons of cargo every year—from clothes to grain and oil—across the world:

Crowded waters: The world’s shipping lanes are now extremely crowded—with traffic jumping 300% between 1992 and 2013. Also: 90% of all of the world’s goods are transported on ships! The problem: Many of these travel right through migration routes and breeding grounds of whales. This depressing (fair warning) animation shows a blue whale doing its best to avoid ships in 2021 off the coast of Chile:

Crowded waters: The world’s shipping lanes are now extremely crowded—with traffic jumping 300% between 1992 and 2013. Also: 90% of all of the world’s goods are transported on ships! The problem: Many of these travel right through migration routes and breeding grounds of whales. This depressing (fair warning) animation shows a blue whale doing its best to avoid ships in 2021 off the coast of Chile:

Ship strikes: The immediate danger, of course, is collision. When ships whiz through these waters, whales are often unable to get out of their way in time. Ship strikes are a leading cause of death for endangered and vulnerable whale populations. But here’s the bigger problem. We don’t really know how many whales die due to such collisions:

[Ecologist Dr Vincent] Raolt says collisions with whales and whale sharks are underreported, in part because many animals sink when struck, and are unlikely to be noticed by ships when they occur. “It’s quite morbid, because usually the only time the captains recognise that they’ve hit a whale is when they pull up the port and there’s literally a whale draped across the bow,” he says.

Devastating noise pollution: As British journalist and author Rose George writes:

The sea is a place of sound, because when light can penetrate only a hundred fathoms below the surface, sound is the best way to communicate… Because water is denser than air, sound travels faster, farther, and more resonantly in it. Consequently, marine animals are vocal beings. They can transmit singing, clicking, calling. With sound, they can gossip, search for mates, avoid fishing gear, communicate. They send out clicks and understand from the echo what is around them and where they are going, just as bats do.

Losing the ability to hear is therefore devastating. Sadly, ships are very noisy—dangerously so. They produce sounds that fall below 100 hz—the frequency at which some whales and other ocean animals communicate. Here’s George again on what being in a shipping lane feels like to them:

I ask Russell Leaper, a researcher at the International Fund for Animal Welfare (IFAW) to translate what the noise of a shipping lane might sound like to a whale. He calls it broadband noise. I want more of a translation. He says, “white noise,” background traffic, something like the constant noise of the freeway that I can hear from my office. It depends on the frequency and proximity of the shipping. Up close, the noise of a ship to a whale would be like standing next to a jet engine, or almost in it.

Data point to note: The “acoustic habitat” of the right whale—the range it needs to hear—has been reduced by 90%. And humpback whales only have 10% of the range they need to find food and a mate.

Surely we’re doing something about this…

Yes. There have been a number of initiatives to minimise whale-ship collisions. One very effective measure: moving shipping lanes. For example: Studies show that if shipping lanes were moved a mere 15 nautical miles south (offshore) of the current routes, then the risk of ship strikes to blue whales will be reduced by a staggering 95%.

In 2007, the US shifted a lane off the coast of Massachusetts to protect fragile baleen and North Atlantic right whales—which reduced the risk of collisions by 81%. The results were just impressive on the California coast. More recently, shipping companies have voluntarily moved their ships—like MSC which is rerouting its routes off the coast of Greece to protect sperm whales. This month, another major shipping company DFDS announced it will do the same.

Also, speed limits: In 2022, US authorities put in new rules placing strict speed limits on ships during critical times of the year. The reason: “A ship travelling at 17 knots would have a 90% chance of killing a whale, but 10 knots gave it a fifty-fifty survival rate.” Last year, 23 shipping companies participated in a speed reduction initiative to protect blue whales in US waters.

Point to note: These container ships are so large, it is difficult for them to avoid hitting whales: “There isn’t opportunity for manoeuvre—the ships can’t suddenly change their course if they see a whale or a fishing boat in their path, so the only way to reduce the risk is to move those ships away from this critical area.”

So what’s the problem in Sri Lanka?

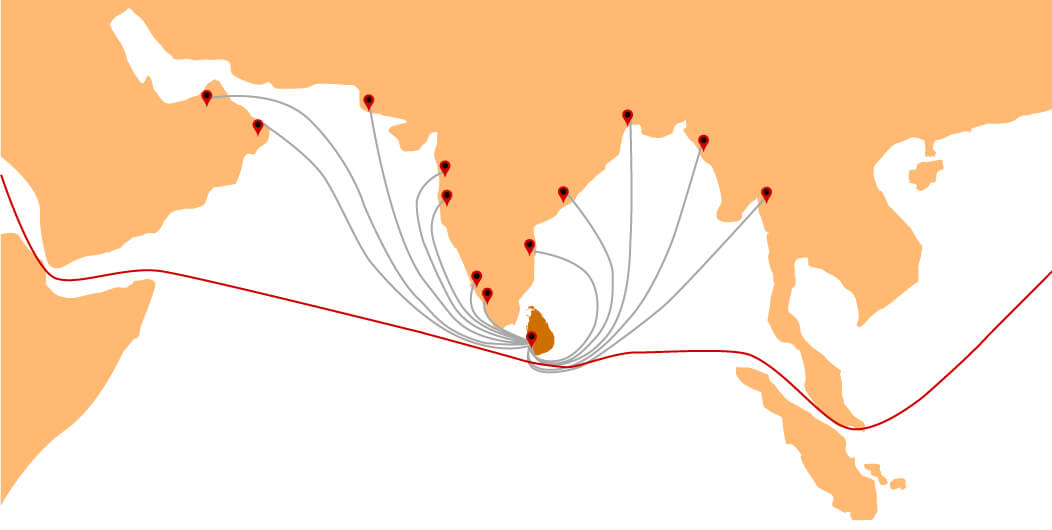

Location, location, location: The island nation is located right next to one of the busiest shipping lanes in the world. The East West shipping route is located 12 nautical miles off the country’s southern end—Dondra Head. Over 40,000 commercial ships travel along this route each year. These include two-thirds of the world’s oil and half of all container shipments:

The blue whale problem: The area is also home to a significant population of blue whales—which live here all year round. They are a unique subspecies not found anywhere else in the world. On an average day, these whales face a barrage of around 200 container ships or oil tankers—which stretch up to 300 metres in length. We don’t know how many whales there are—or how many have been killed (since many sink into the sea). All we have is a 2017 study that revealed half of the recorded deaths of blue whales in Sri Lanka were due to ship strikes.

Environmentalists are convinced they are in great danger:

The risk is so high that we know that there must be many more being killed than are being reported. The blue whale might be the largest animal on the planet – these ones are about 22 metres long – but they pale in significance against a 300-metre cargo ship.

The solution: Experts argue moving the shipping lane by 15 nautical miles to the south, the risk to these whales can be reduced by 95%. In April, the International Maritime Organization—a UN body that regulates global shipping—the World Shipping Council—which represents the major shipping companies in the world—and environmentalists presented a proposal to do just that.

Point to note: Sri Lanka has been repeatedly asked to move the lane since 2015—with the unexpected support of shipping companies. Their reasoning:

This is one of the few cases in the world where we can physically separate ships from where the whales are. Yes, it adds a little distance, fuel and money to shipping costs, but the extra cost is really minor… There are other places in the world where doing this would incur significant fuel costs or add a lot of time to the journey that businesses will not be happy to absorb.

In fact, some big shipping companies like MSC have already moved their route voluntarily.

The problem for Sri Lanka: The new shipping lane will be located 76 nautical miles away from Colombo, 25.6 nautical miles away from Galle, and 26.9 nautical miles away from the Hambantota Port. Colombo is worried that the shift will make its biggest ports less attractive to shipping companies:

Maritime expert Ayesh Ranawaka said sending ships on a detour would have an immediate economic impact. The prospect of ships having to sail a longer distance will make it less likely that they will choose to dock in Sri Lanka for refueling and other services. And the revenue that ports like Hambantota would be missing out on wouldn’t be compensated for by the growth of the whale-watching industry in Mirissa, Ranawaka said.

The conspiracy theory: Sri Lanka also suspects “geopolitical motives” for this seemingly benevolent proposal—since any loss to SL will be a gain for ports in Singapore and the UAE. In fact, many experts quoted in the local media insist that there is no hard evidence that whales are dying or in danger due to ship collisions:

There is no first-hand data and records to justify this claim of whales getting hit by ships along the maritime route around Sri Lanka. Even those school-going kids know that whales are one of the most intelligent and sensitive creatures in the sea. How can you believe that such a creature with proper senses would not realise a ship moving in its direction to get hit and die?

The bottomline: India too is vying to become a key destination for global shipping—which is why we are building a mega-port in Vizhinjam. In fact, most of the southern states are on a port-building spree. There are no whales involved, but there are similar concerns about their impact on marine habitats and local fishing communities.

Reading list

The best big picture is in Cosmos magazine and the Scientific American. For more on the push to shift the Sri Lanka lane, read The Guardian, Mongabay and Live Science. Sri Lankan media—including Sunday Times and NewsFirst—offer the government’s point of view. Bloomberg News and The Guardian look at innovative tech solutions to minimise collisions. ICYMI: Orcas have been attacking boats off the Iberian coast—perhaps due to previous trauma—Scientific American has more on that.

souk picks

souk picks