Sign up for Advisory! It’s free and so is our exclusive

welcome

aboard travel guide to Kyoto.

Our weekly goodie bag includes:

What you won’t get: Spam or AI slop!

Already a user ? Login

Privacy Policy. You can unsubscribe any time.Tell us a bit more about yourself to complete your profile.

Thank you for joining our community.

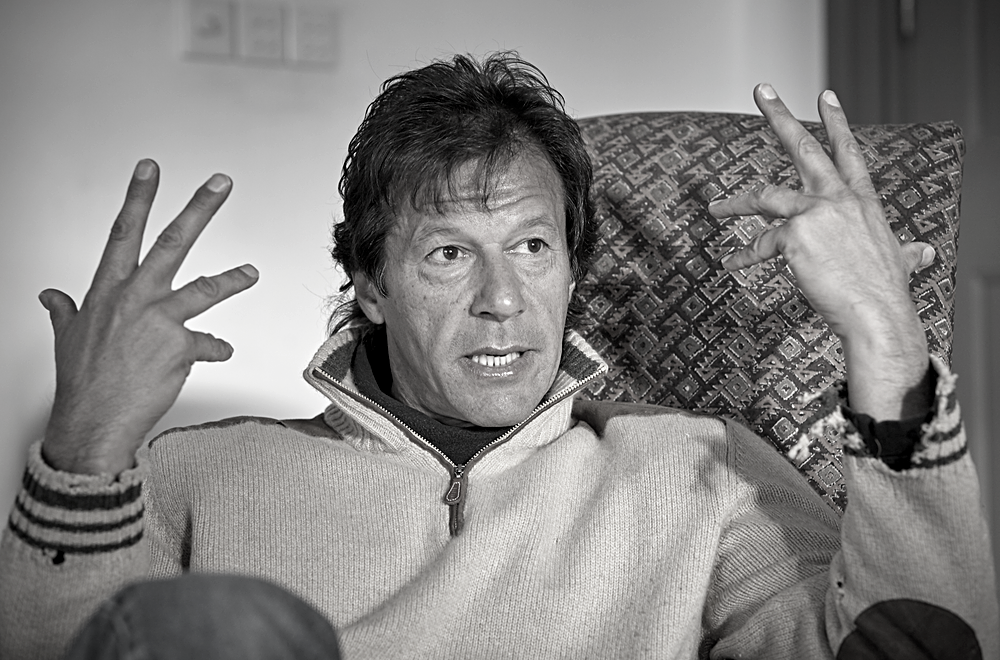

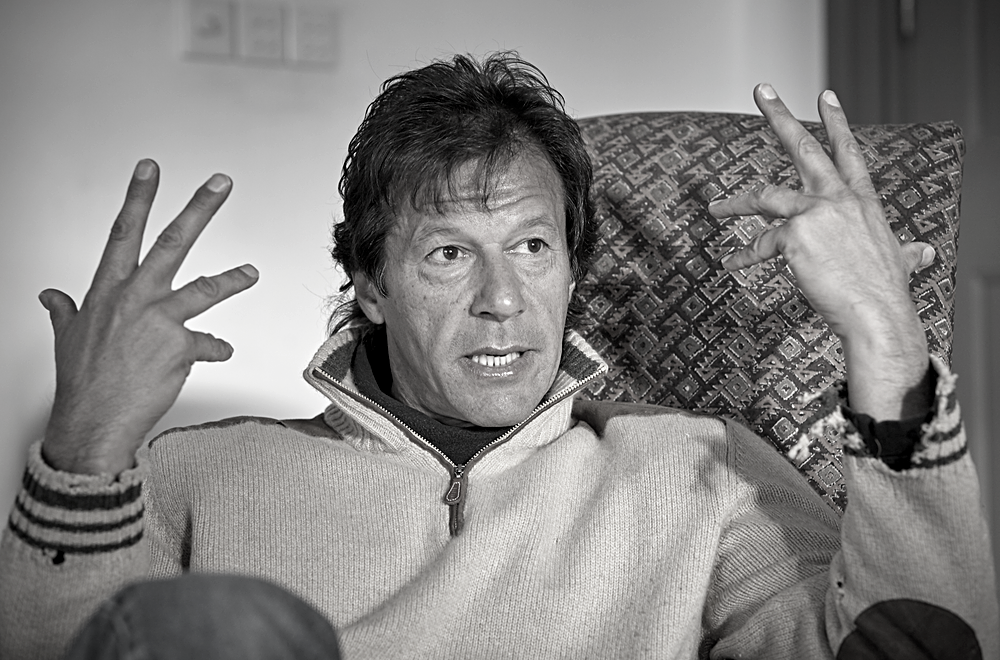

The Pakistani prime minister faces a no-confidence motion in Parliament today—which he is most likely to lose. But the justification offered by the Opposition—economic mismanagement—has little to do with the ignominious end of his tenure. The real reason: The Pakistan military is tired of their Khan experiment and is looking for a way to dump him.

Researched by: Sara Varghese

Here’s what you need to know about Khan’s rise to power:

Why the army chose Khan: The establishment liked Khan for several reasons:

The rigged election: The army’s main aim in the 2018 election was to ensure that Nawaz Sharif did not return to power—and revive his prosecution of former president General Musharaff which would challenge the army’s supremacy. Hence, it did everything possible to pull off “the dirtiest elections in the history of the country”:

The result: Despite all this ‘match-fixing’, Khan could not secure a clear majority—winning only 32% of the vote. But he easily put together a coalition government with smaller parties—which has now proven to be an advantage for the military. It has made it all that easier to pull the plug on his prime ministership.

The motion: will be introduced in the lower house, the National Assembly, today. If it succeeds, Khan will be summarily dismissed along with his cabinet ministers.

The architects: All the opposition parties have signed on—including the Bhutto-family led PPP and Sharif’s PMLN which is part of a separate opposition alliance called the Pakistan Democratic Movement (PDM). Adding to their numbers: Khan’s coalition partners who seem ready to abandon him plus 12 members of his own party Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf.

The math: The National Assembly has 342 seats of which Khan’s PTI had 179—including 17 seats held by coalition partners. The Opposition has 162 seats. All it needs are 10 defections to reach the magic number of 172 to oust Khan. Khan’s party is vowing to fight “to the last ball”—but its prospects look grim. Point to note: In Pakistan’s history, the only two prime ministers to have faced a no-confidence motion—Benazir Bhutto in 1989 and Shaukat Aziz in 2006—and both survived the move. Khan may become a historic first-to-lose.

The justification: The raison d’etre for the motion is the economic chaos in Pakistan. It faces one of the worst inflation crises in Asia, with food and fuel rising 15.1% last week from a year earlier. The rupee hit a historic low of Rs 180 against the dollar—and growth has been exceedingly slow. There is no mistaking the rising public anger against Khan—almost half of Pakistanis have an unfavourable view of Khan’s performance, compared to 36% in favour. And it offers an opportune moment to strike against him.

Not helping: Khan’s response to the mounting opposition. On inflation, he said: “I am not here to check tomato and potato prices, but to raise a nation.” And he has threatened to stage a huge rally of his supporters outside the Parliament today—potentially blocking lawmakers from entering the building.

Khan’s successor: If the no-confidence motion goes through, the Opposition will be able to show a majority in the assembly without holding an election. It is likely that Khan’s replacement will be Shehbaz Sharif—Nawaz Sharif’s brother and president of the PMLN party.

Point to note: Others point out that the economy is just an excuse to oust Khan. What we’re seeing is the Opposition playing to the army’s script:

"[His] economic performance has been a mixed bag if it’s graded on a curve and with the caveat that his government not only inherited an economic crisis but had to navigate a global pandemic… We have to ask ourselves, why is it that every single elected prime minister faces these ouster challenges and why not a single one has ever completed a full five-year term?"

The army has sent a clear signal that it will not defend Khan—with opposition leaders declaring, “Today we see they are neutral…Political players are making their decisions without pressure.” This “neutrality” is itself “a powerful signal”—which Khan has received loud and clear. His response: “Humans either side with good or evil. Only animals remain neutral.”

So why did Khan—the military's golden boy—fall from its good graces? The answer: He crossed three red lines.

One: The most powerful position in Pakistan is not the Prime Minister but the Chief of Army Staff—who is General Qamar Javed Bajwa. When Bajwa wanted to transfer Lt General Faiz Hameed from his post as chief of the Inter-Services Intelligence, Khan resisted—in his desire to anoint Hameed as Bajwa’s eventual successor. He took three weeks to finally approve Bajwa’s choice for the new ISI head. This challenged one of the military’s cardinal rules, as Mohammad Taqi notes: “[T]he Pakistan army gets to pick favourites among the civilians; it doesn’t allow civilians to pick their favourite generals.”

Point to note: The Opposition was also relieved that Khan was not able to groom his man Hameed as the next army chief—which would have given him absolute and indefinite power:

“Everyone and his aunt in Pakistan knows that General Hameed is an insurance policy for Imran’s stay in power…If he goes, it would become difficult for Imran Khan to survive right now, forget about winning the next general election.”

Two: Khan’s disastrous foreign policy did not win him any favours either. He put all his eggs in the Chinese basket—and became stridently opposed to the US and its Western allies. For starters, the army did not appreciate Khan taking calls on national security—which it considers as its sole preserve. And it does not view a blatant pro-China tilt as wise:

“Because as US-China competition intensifies, Pakistan’s army fears getting trapped in a cul-de-sac with Beijing. So it seeks to balance the two great powers by grasping on to areas of cooperation, including counterterrorism and trade, that could salvage relations with Washington.”

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine—which Khan blatantly blessed by arriving in Moscow on its eve—makes the army all the more jittery about being trapped by China’s “cold war” strategy.

Point to note: Not helping Khan’s cause: The fact that Beijing has been a less-than-generous patron:

“The Imran-Bajwa duo miscalculated that China would replace the US as Pakistan’s chief financial benefactor. But that didn’t happen. The regime discovered that unlike the US, the Chinese are both stingy paymasters and hard taskmasters. With a clueless economic team at the helm… even the high-markup Chinese loans and investments… effectively stalled.”

Another example: When Islamabad tried to renegotiate the expensive electric power contracts with Chinese companies, Beijing not only refused to do so, but it insisted on repayment of $1.4 billion in arrears.

Three: The “hybrid arrangement” with Khan only worked as long as the military remained relatively out of sight—and out of the line of fire. But rising economic woes fueled popular anger not just at Khan but also his army patrons—which the Opposition jumped on with glee:

“While the public’s anger was initially directed at Khan, it also pointed the finger of blame at his patron and handler—the Pakistan army. Nawaz [Sharif] capitalised on the discontent and went after the army all guns blazing. He called out, by name… [Army chief] Bajwa and [ISI head] Faiz Hameed Chaudhry… for derailing the economy and foisting upon the country an incredibly inept prime minister.”

Point to note: Soon after Hameed’s ouster, the new ISI chief started sending out feelers to opposition leaders—and cut a deal where Sharif’s party would stop openly criticising the military. In return, the establishment would stop interfering in local elections in Khan’s favour.

The bottomline: Imran Khan does not plan to go quietly into the night—and has rejected the military’s suggestion that he resign ahead of the vote. But without the coercive force of the establishment—which won him the election—his resistance is likely to be futile. The rise of Shehbaz Sharif indicates that he will be far more amenable to cooperating with the army than his brother Nawaz. So we’ll probably get another national election and yet another “hybrid arrangement.” More things change…

The Hindu, Deutsche Welle and Indian Express offer a good overview of the state of play. Caravan magazine (paywall), ORF Online and BloombergQuint have a great analysis of how Khan won his election. Mohammad Taqi in The Wire and The Nation offer the best take on why Khan lost favour with the army. New York Times has an interesting analysis of why the Pakistan army wants the US back in the region.

Spark some joy! Discover why smart, curious people around the world swear by Splainer!

Sign Up Here!

souk picks

souk picks