Sign up for Advisory! It’s free and so is our exclusive

welcome

aboard travel guide to Kyoto.

Our weekly goodie bag includes:

What you won’t get: Spam or AI slop!

Already a user ? Login

Privacy Policy. You can unsubscribe any time.Tell us a bit more about yourself to complete your profile.

Thank you for joining our community.

190 countries met in Glasgow amid a great sense of urgency about the future of a rapidly warming planet. After two weeks of haggling and compromises, we have an agreement—which offers a far better chance of real change, but without guarantees that it will happen.

Editor’s note: We offered detailed context on this summit in our previous explainer. Do check it out if you haven’t been following COP26 coverage.

What is COP26: COP is shorthand for the Conference of the Parties to the UN Convention on Climate Change—an annual meeting of countries which meet to craft a shared strategy to save the planet. One such meeting—COP21—resulted in the Paris Agreement—which was the first to set the goal of limiting global warming to below 2°C, preferably 1.5°C.

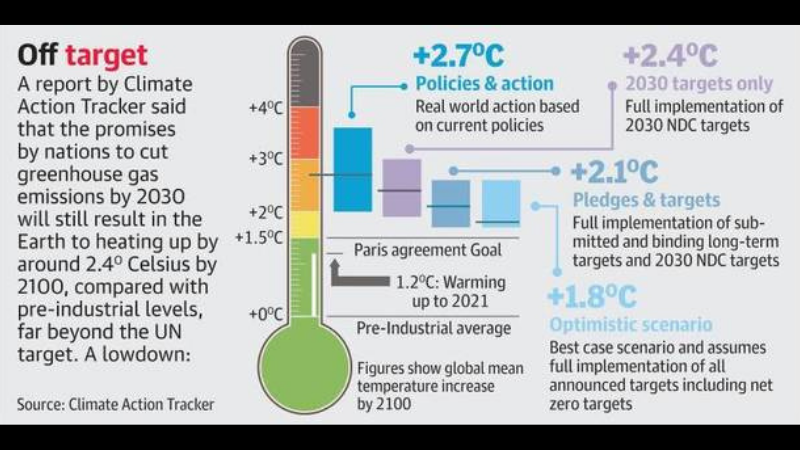

Why it matters: A number of big reports released this year show that the world is on a catastrophic path. Right now—given the current pledges to cut greenhouse gas emissions—we are on track for an average 2.7°C temperature rise this century! So there was immense pressure on this conference to come up with a plan for immediate and drastic action.

NDCs defined: This shared strategy requires each country to define and commit to their Nationally Determined Contributions—their individual national plan to slash greenhouse gas emissions to meet the Paris Agreement goals.

Aiming for net zero: The term ‘net zero’ refers to the difference between the amount of greenhouse gases produced and the amount removed from the atmosphere. We reach net zero when what we add is equal to what we take out. And if the world hits that target by 2050, we can restrict global warming to 1.5°C.

Before the summit, the planet was on track to warm by 2.7°C by 2100. The pledges to cut emissions made in the Paris agreement were far too modest to meet the target of limiting global warming to 1.5°C. And most of the countries did not meet their commitments.

The good news: Thanks to the fresh set of climate pledges—including commitments to achieve net zero—we are now on course to warm by roughly 1.8°C.

Big upside to note: Every fraction of a degree counts when it comes to averting climate change—since even the smallest increase implies more extreme weather and higher sea levels. As a Maldives minister put it, “The difference between 1.5 and 2 degrees is a death sentence for us.”

And the COP26 agreement keeps that goal of limiting temperature rise to 1.5°C alive—despite fierce resistance from oil-producing countries like Saudi Arabia and Russia:

“The Glasgow pact ‘resolves to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C’ and ‘recognizes that limiting global warming to 1.5°C requires rapid, deep and sustained reductions in global greenhouse gas emissions.’ It’s still not an official target, but the greater emphasis on it means that NDCs and other climate goals put forward by countries will be evaluated based on how close they hew to this goal.”

The not-so-good news: The current plans allow emissions to rise 13% by 2030 compared with 2010. Scientists say they must fall 45% to hit the 1.5 degree target. And as this Climate Action Tracker chart makes clear, even the 1.8°C projection is the most optimistic scenario (tap to zoom):

The good news: World leaders have discussed climate change 26 times since the 1990s, but issuing a call to reduce the use of fossil fuels like coal, oil and gas remained a big no-no. For the first time, the agreement makes it explicit that fossil fuels have to go.

The India intervention: The initial draft called on countries to “accelerate the phasing-out of coal and subsidies for fossil fuels.” But India took objection to the language and refused to sign on—until it was changed to “phase down.” The reason offered by the Environment Minister:

“How can anyone expect that developing countries can make promises about phasing out fossil fuel and coal subsidies? Developing countries still have to deal with their development agenda and poverty eradication.”

As a result, a number of other countries and climate change activists are unhappy with New Delhi: “India’s last-minute change to the language... is quite shocking. India has long been a blocker on climate action, but I have never seen it done so publicly.”

OTOH, Indian representatives gave the example of subsidies for LPG cylinders to low-income households: “This subsidy has been of great help in almost eliminating biomass burning for cooking and improved health from reduction in indoor air pollution.”

Moment to note: UK Minister and COP26 president Alok Sharma fought back tears as he offered an emotional apology for the last-minute change:

Less than a fifth of the world has been responsible for three-fifths of all past emissions. The US and the EU alone have contributed a whopping 45%. Developing countries rightly argue that the burden of correcting the current state of affairs should fall on their shoulders.

Also this: As part of the Paris Agreement, developed countries promised $100 billion a year in financial assistance to less advanced nations to help them cut emissions—which will impose a staggering price on their economies. But they have not delivered—finally reaching only $80 billion a year as of 2019. But most of that money has gone toward cutting emissions—not helping these countries cope with extreme weather changes that are now inevitable like storms, wildfires, droughts.

Important data point to note: The price for developing countries to adapt to climate change could reach $300 billion a year by the end of the decade.

The no-good news: A big goal of COP26 was to get the wealthy countries to at least deliver on their promise of $100 billion/year—which now likely won’t happen until 2023. In earlier drafts, developing countries asked for $1.3 trillion/year by 2030. But the final agreement simply kicks the can down the road:

“In the final compromise, countries agreed to begin a two-year work plan ending in 2024 to settle on how climate finance will ramp up to meet the needs of the most vulnerable nations in the future. In the meantime, developed countries agreed to collectively double funding for climate adaptation projects by 2025.”

And there are no funding targets or mechanisms in place in the current agreement.

The bottomline: Most of us are rightly sceptical about these global agreements—which are often more talk than action. As the Wall Street Journal notes:

“It has no enforcement mechanism, relying instead on the good faith of the world’s governments to adhere to its rules as best they can. In key areas, it doesn’t require nations to act, but merely urges or requests them to do so, reflecting wiggle room that was needed to achieve consensus among all governments.”

Vox has the most detailed overview of the final agreement—and smaller pledges made on the sidelines. The Verge details the big fail on climate finance—and why it matters. The Hindu, the Telegraph and NPR have more on India’s intervention on coal. Bloomberg News explains the new rules set for carbon markets—where countries who are struggling to meet their emission targets can buy credits from others who have surpassed their goals.

Spark some joy! Discover why smart, curious people around the world swear by Splainer!

Sign Up Here!

souk picks

souk picks