This is the delayed part two of our series on Rajendra Chola. In part one, we looked at how the ancient king is being recast as the great South Indian Saviour of Hindu pride. In part two, we cut through mythmaking to trace the history of the Chola dynasty and the conqueror par excellence—who presided over the not-so ‘golden age of Tamils’. Fair warning: our hero has feet of A-grade clay—and is not quite the Dravidian hero Stalin hearts.

Editor’s note: You can check out the political battle between the BJP and DMK over Rajendra Chola in part one. There aren’t many Big Stories left in the calendar—before we shut the newsroom on August 29. So be sure to write in if you want us to do one on a burning topic of your choice. Email us at talktous@splainer.in

About the lead image: The stone carving is located in Kolaramma Temple and shows Rajendra Chola in Battle.

First, the backstory

The ancient dynasty has never received the same level of national attention—or inspired as much angst—as the Mughals. But the Cholas have long enjoyed pop culture clout thanks to the iconic Tamil novel ‘Ponniyin Selvan’ written by Kalki Krishnamurthi in the 1950s. The book made national headlines once again in 2022 as a two-part cinematic opus directed by Mani Ratnam—starring Aishwarya Rai and Vikram. Needless to say, the great fiction bears little resemblance to fact.

Tamilakam, explained: That’s the name given to the ancient homeland of the Tamil people. It was ruled by Three Crowned Kings from the beginning of the Common Era and through the medieval era—the Pandya, Chera, and Chola dynasties. Each fought the others for dominance—and were together called ‘muvendar’.

First came the Pandyas: Mentions of Pandya kings first appear in Greek writings in the fourth century BCE—and they are said to have later sent ambassadors to Rome. Their capital was Madurai—and they were Jains before converting to Shaivism (the dominant religion of all three dynasties). The Pandya dynasty lasted as late as the 16th century—finally disintegrating due to regional conflicts and incursions by Islamic invaders.

Rise of the Cholas: Records of a Chola dynasty date back to the 2nd and 3rd centuries BCE. But the Chola empire we all know and revere was established in 848 CE by Vijayalaya—a descendant of the Early Cholas. In 850 CE, he seized Thanjavur—while the two local superpowers—Pallavas and Pandyas—were busy fighting one another. In 885 CE, the Cholas expanded into what we know today as Karnataka—and finally rose to prominence under King Rajaraja ( 985–1014 CE). He extended the empire into southern Karnataka, coastal Andhra Pradesh, and northern Sri Lanka:

The Chola control over the entire southern coastline is remembered today in the Tamil term for the eastern coast — Coromandel, which is a corruption of Cholamandala, meaning ‘Circle of Chola Rule.’

Interesting bit of trivia: The dancing Siva (Nataraja) evolved under the aegis of the Cholas—specifically Rajaraja. You can see one such artefact from the 11th century below:

Enter Rajendra Chola: The not-so-great conqueror

While Rajaraja extended Chola power in the southern peninsula—his heir Rajendra consolidated and expanded the empire across the seas—as far as modern-day Indonesia. Rajendra inherited the throne in 1014 CE—and soon set about his ambition to become the “universal emperor, with authority emanating to all points of the known world.”

Building an empire: Rajendra’s campaign began in his neighborhood—subjugating all of Sri Lanka, defeating the Chalukyas to the West and Pandyas to the South. More novel was his strategy of using a conquered kingdom’s regalia to crown his sons as “sub-kings,” bearing titles like “Chola Lord of Lanka” or “Chola-Pandya” etc. In 1021, he even led a successful expedition to the Indo-Gangetic plains—whose 1000th anniversary was recently celebrated with great pomp, with PM Modi as the chief guest.

But, but, but: The military campaign—now being reframed as a symbol of Hindu pride and might—was anything but:

Between 1022 and 1023, as Aniruddh Kanisetti shows in his work on the ‘Cholas, Lords of Earth and Sea’, Rajendra’s massive army killed, raped and plundered its way north for what was to be a “raid on the Ganga” to bring its water so that he could consecrate himself as “king of kings”... Along the way, Rajendra’s soldiers sacked temples and stole their idols, while he waited for them to return with the water collected from the Ganga on the southern bank of the Godavari.

Kanisetti writes that it is “difficult to believe that these idols were obtained without extreme violence against the lords that derived power from them, to say nothing of the population displaced and brutalised by roving armed men”.

Rajendra was not interested in annexing these lands—or establishing vassal states. The sole goal of this violent, brutal campaign was symbolic—to establish himself as the “universal emperor.” So it’s a bit ironic that Modi-ji brought with him Ganga jal from the North to commemorate Rajendra’s victory.

Point to note: This path to becoming the ‘universal emperor’ wasn’t new. The legendary Gupta king Raghu in the North had already taken a shot at the title back in 4th century CE:

We can see that the motivation for war is not annexation. In none of his expeditions does Raghu set up a governorship or viceroyalty. Rather, he is motivated by tribute and by symbolism: by displaying his overwhelming military might (and virility) in all four cardinal directions, thus performing a digvijaya or “Conquest of the Directions” — he establishes himself as a universal sovereign, a chakravartin.

Though in Modi-ji’s defence: The DMK version of Chola mythmaking is no less inventive. CM Stalin recently declared that DMK rule should be remembered as the “golden period of Tamil Nadu”—as is the reign of Cholas. Except the backbone of the Chola “tax and military apparatus” was a powerful landlord caste—who “were completely unafraid to use brutality to keep their tenants, serfs and slaves in line.” Cholas were “a group of elites — including local strongmen, landlords, temple institutions, and Brahmins assemblies — that collaborated to generate revenue from land, often fighting to keep as much wealth for themselves as possible.” So not quite the Dravidian heroes the DMK makes them out to be.

Rajendra Chola: Emperor of the seas

Rajendra was the first Southern emperor to have the imagination, audacity and ambition to send his military eastward, across the seas. In his first and most important campaign, he took aim at Kedah on the Malayan peninsula—a “long-standing but difficult trading partner for the Tamil coast” known in Tamil as Kadaram.

Location, location, location: Part of the broader Srivijaya empire, Kedah had built its wealth by selling exotic wood, camphor, and spices—sourced from the Indonesian archipelago—and sold to courts and temples across the Indian Ocean. Thanks to geographical proximity, the Srivijaya dynasty also had dibs on China—”perhaps the most important destination of international commerce in those times.”

Its officials controlled not just access but also information about more distant lands (for example, India):

Ancient sources say the Srivijayas, in an act of spectacular mischief, made it appear to the Chinese that the Cholas were a minor kingdom who were dependent on the Srivijaya empire. In fact, one source even mentions the Srivijaya rulers speaking about how they wrote to the Chola emperors “on coarse paper” as if they were not worth the effort of something fancier. This impressive impression management of the Cholas by the Srivijaya empire lasted at least till the 1070s if not later, and the Song dynasty continued to believe that the Cholas were at best a middle-grade empire of little ambition.

In the Srivijayas, Rajendra and Tamil traders found common cause—which in turn birthed a powerful naval fleet—and an unprecedented overseas adventure.

Enter, the Tamil East India Company: Rajendra’s key ally was a “great Tamil merchant corporation” known as the Ainurruvar or the Five Hundred. They were present in great numbers in the kingdom—often serving as ambassadors to the Chinese court: “As such, they had front-row seats to Kedah’s commercial ambitions, as well as Rajendra Chola’s political necessities.” Kedah could not have been conquered without them:

Rajendra’s court had worked out most of the details. Conveyed by the great annual merchant fleet, Chola troops would attack and loot Kedah. The Five Hundred would expand into the political vacuum and soak up the profits. And so the centuries-old histories of three great powers in Monsoon Asia – the Chola state, the ports of Southeast Asia and the Tamil merchant corporations – moved towards a tremendous collision.

The really interesting bit: Rajendra did not establish an outpost in Kedah. He tore down a city gate—took it back home and proclaimed himself Kedah-Seizer, Kadaram-Konda. The victory became instead a foothold for a sprawling trade empire—and sowed the seeds of a Tamil diaspora that remains to this day:

While some Indian nationalists have proclaimed this to be a Chola "conquest" or "colonisation" in Southeast Asia, archaeology suggests a stranger picture: the Cholas didn't seem to have a navy of their own, but under them, a wave of Tamil diaspora merchants spread across the Bay of Bengal.

By the late 11th Century, these merchants ran independent ports in northern Sumatra. A century later, they were deep in present-day Myanmar and Thailand, and worked as tax collectors in Java. In the 13th Century, in Mongol-ruled China under the descendants of Kublai Khan, Tamil merchants ran successful businesses in the port of Quanzhou, and even erected a temple to Shiva on the coast of the East China Sea.

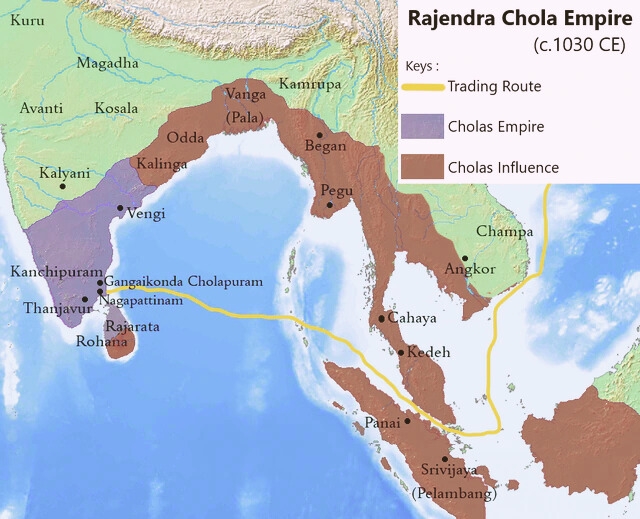

You can see what the map looked like in 1030 CE:

The bigger picture: Anirudh Kanisetti points out that no other Indian king ever attempted or replicated Rajendra’s astonishing maritime victory. Not even Rajendra sent a second expedition. The reason: the merchants no longer had any need for it. It was far too costly and risky to attempt an overseas campaign without their support. Besides, the Cholas too had what they wanted—to become “a cultural and economic behemoth, the nexus of planetary trade networks.”

The bottomline: It’s absurd how much time and energy we as a democracy expend on long-dead kings and dynasties—be it as villains or heroes.

Reading list

For the history of the Cholas, read India Today and BBC News. We recommend Anirudh Kanisetti’s fascinating Print essay on the Tamil merchant guild, the brutal reality of Chola rule. He also offers this detailed account of the siege of Kedah in Scroll. Nirupama Subramanian in The Tribune explains why Modi’s attempt to appropriate Rajendra Chola is entirely misplaced. Aditya Iyengar in Scroll explains how ‘fake news’ sparked the conquest of Kedah. Edexlive speaks to historian Stalin Rajangam who debunks the myth of the ‘golden era of the Tamils’ in detail.

souk picks

souk picks