Boro Din in Kolkata feat. bhapa doi cake

Editor’s note: Christmas in Kolkata—Boro Din, as it’s called—is an adventure in its own right. Armenian prayer services, Christmas carols in Bangla, showers of fake snow, jolly Santas in rickshaws—the journey is a thrilling one. And, of course, the endless plates of glorious Kolkatan Christmas food. City-born journalist Dipanjan Sinha takes us on a scintillating walkthrough of the city during Christmas, a time of inclusive merriment—via chelo kebab at Peter Cat, bhapa doi Christmas cake, streetside momos, and a Calcutta-Chinese dinner. We’re starving now!

Written by: Dipanjan Sinha

*****

Shall I compare thee to a Calcutta winter morning?

I have always wanted to open with this line, ever since I encountered Shakespeare’s sonnets as a schoolboy. “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?” he wrote admiring his beloved. I remember being baffled. How could a summer’s day be beautiful? In Calcutta, summers meant relentless heat, sticky humidity, and power cuts that left us fanning ourselves with old copies of Anandabazar Patrika.

My childhood years had me playing in monsoon-soaked streets, surviving dramatic kalboishakhis amid the occasional mercy of a nor’wester. As such, the only season worthy of poetry was winter. The air turned crisp, the light golden, and the city felt alive in a way nothing else matched. Even the everyday smells sharpened: the kathi-rollwala turning eggs on his tawa, the telebhaja stall frying beguni and phuluri in the blue evening smoke that hung low over halogen-lit central Calcutta lanes.

This small confusion was my earliest lesson in how beauty is cultural and geographical. Summer was “temperate” and “eternal” to an Englishman, but to a young Calcuttan, the gentle embrace of December and January made the cut.

I have since lived in or lingered long in every Indian metro: Mumbai’s sleepless rush, Delhi’s winter gardens, Chennai’s sea-salt breeze, Bangalore’s pleasant parks with its happening MG Road. I have chased colder winters in the hills and denser fogs up north. But nothing has ever come close to the quiet perfection of a Calcutta winter. It is just cold enough to pull out the sweater bought years ago from the bustling New Market (map), yet never harsh enough to bite.

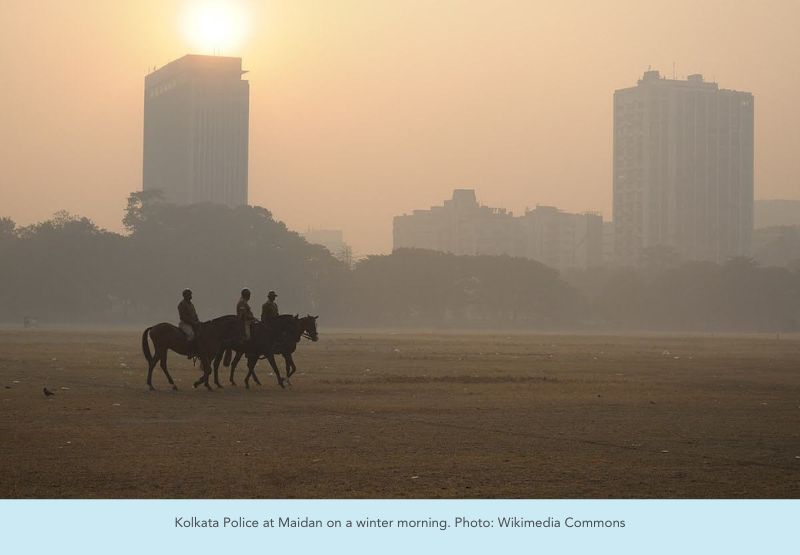

The sun rises soft and low, wrapping Maidan in a haze that feels like a secret the city holds close to its chest. This urban green space of nearly 988 acres is often called the lungs of the city but has a deep association with its heart too. Stretching from the Hooghly River to the Victoria Memorial (map), it houses landmarks like Eden Gardens (map). In winter mornings, the Maidan is wrapped in dew and fog to only wake up with lazy winter rays as the day rolls into noon.

But the true magic begins when that winter chill settles mid-December, and the first miniature Christmas trees appear at hawkers' stalls in Gariahat, the South Calcutta textile-shopping Mecca. They pop up at Esplanade too—Calcutta’s dimestore Times Square. The countdown to Boro Din—the Big Day—as Bengalis have always called Christmas, begins. And Calcutta turns into one long party I never want to leave. Like Shakespeare’s English summer crossed oceans to become my crisp Calcutta winter, the quiet Bethlehem night becomes our loud, luminous, nonchalantly secular Boro Din.

But the true magic begins when that winter chill settles mid-December, and the first miniature Christmas trees appear at hawkers' stalls in Gariahat, the South Calcutta textile-shopping Mecca. They pop up at Esplanade too—Calcutta’s dimestore Times Square. The countdown to Boro Din—the Big Day—as Bengalis have always called Christmas, begins. And Calcutta turns into one long party I never want to leave. Like Shakespeare’s English summer crossed oceans to become my crisp Calcutta winter, the quiet Bethlehem night becomes our loud, luminous, nonchalantly secular Boro Din.

It all starts, inevitably, with the cakes. Sometimes weeks before December 25. The queues at Nahoum & Sons in New Market grow longer. Founded in 1902 by a Baghdadi Jew, Nahoum Israel Mordecai, it is one of the last surviving relics of Calcutta’s once-thriving Jewish community.

It all starts, inevitably, with the cakes. Sometimes weeks before December 25. The queues at Nahoum & Sons in New Market grow longer. Founded in 1902 by a Baghdadi Jew, Nahoum Israel Mordecai, it is one of the last surviving relics of Calcutta’s once-thriving Jewish community.

Every December, people from every faith, or none, stand patiently outside its counters. The rich plum cakes and fruit cakes, still prepared by Muslim master-bakers who inherited the recipes generations ago, are wrapped in plain butter paper and carried home like treasure. In a time when everything feels polarised, the sight of that queue (despite becoming a social media cliché) remains a stubborn reminder of the soul of the city.

These are grown-up thoughts. When I first queued up as a teenager with my father, nobody was thinking of woke metaphors. We were just there for the smell drifting from the bakery, the promise of rum-soaked fruit and buttery crumb. I still try to buy one every year; the morning after, a thick slice with black coffee is my private little ritual of the season.

If Nahoum’s queue feels impossible to tackle, no need to despair.

The popular bakery and cafe Flurys on Park Street offers its own legendary Christmas cake — lighter, Swiss-inflected, beautifully iced. The old Great Eastern Hotel bakery (now Lalit Great Eastern) still produces excellent rich fruit cake for those who prefer tradition with colonial grandeur.

And these days, festive cakes have become so ubiquitous, almost every neighbourhood confectionery has a special. If you are a little wild in your choice of fusions, you can even try the Christmas twists of the traditional sweet shops (mostly Hindu-owned) like Balaram Mullick’s plum cake sandesh or their bhapa doi cake.

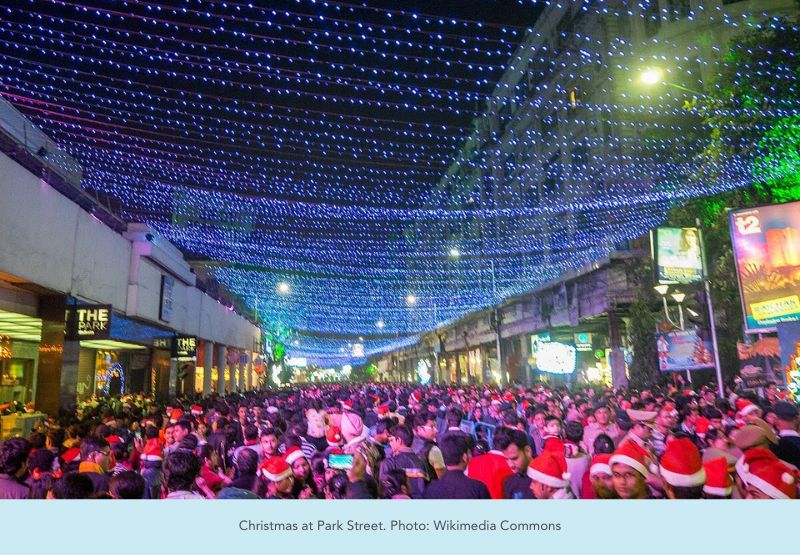

But Christmas in Calcutta was never just about the cakes. It is a carnival that belongs to everyone. Park Street turns into a river of light. Artisans from across the Hooghly in Chandannagar string up their famous giant stars, bells, cascading curtains of LEDs that make the whole street glow like something out of a childhood picture book. On the busiest nights the road is closed to traffic and families stroll down the middle.

This stroll, however, is not for the faint hearted anymore as the crowds keep swelling every year and the walk becomes harder.

Street stalls sell momos, rolls, phuchka, ghugni, hot chocolate, and roasted peanuts. Live bands play at Allen Park beneath the giant Christmas tree; carols in English, Bengali, and Hindi float over the crowd. For me, walking there still feels like soaking in the energy of a city that loves to celebrate.

Street stalls sell momos, rolls, phuchka, ghugni, hot chocolate, and roasted peanuts. Live bands play at Allen Park beneath the giant Christmas tree; carols in English, Bengali, and Hindi float over the crowd. For me, walking there still feels like soaking in the energy of a city that loves to celebrate.

It is not all crowds and crazy though; a short walk away, St. Paul’s Cathedral lights up its Indo-Gothic spires for midnight mass, and the hymns drift out into the cool night, mingling with the sounds of the winter city night.

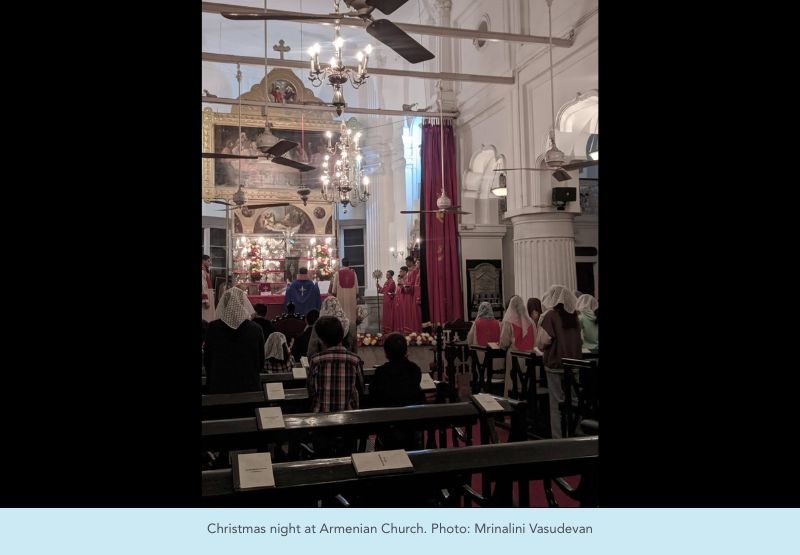

Quieter still, slip into the tiny Armenian Church of the Holy Nazareth on Brabourne Road—the oldest functioning church in Calcutta. A few remaining Armenian families and local Catholics hold a short, hauntingly beautiful service in Armenian and English, then share rose cookies and homemade cake in the courtyard under a sky most people never notice.

For a more community experience, there is Bow Barracks—my favourite corner of Christmas Calcutta. The red-brick Anglo-Indian enclave comes alive with handmade paper stars, tinsel, and fairy lights strung across every balcony. The music? Old Elvis, Cliff Richard, Jim Reeves mixing with some new numbers pours out of open windows. There are community dances in the lanes, impromptu football matches, long tables of homemade food, and yes, plenty of cake and homemade grape wine passed around. Children wait for Santa on his annual rickshaw ride. I have spent some prized evenings there feeling the old city’s warmth in my bones.

For a more community experience, there is Bow Barracks—my favourite corner of Christmas Calcutta. The red-brick Anglo-Indian enclave comes alive with handmade paper stars, tinsel, and fairy lights strung across every balcony. The music? Old Elvis, Cliff Richard, Jim Reeves mixing with some new numbers pours out of open windows. There are community dances in the lanes, impromptu football matches, long tables of homemade food, and yes, plenty of cake and homemade grape wine passed around. Children wait for Santa on his annual rickshaw ride. I have spent some prized evenings there feeling the old city’s warmth in my bones.

There is no way we can talk about Bow Barracks and Calcutta’s Christian community without mentioning songwriter-filmmaker Anjan Dutt, the principal poet of Calcutta Christmas, Anjan Dutt. His songs blending Blues and Bengali traditions stormed teen tape recorders for three decades since the late ’90s. His 1998 Hindi film Bada Din, starring ’90s supermodel Marc Robinson and Shabana Azmi, and the 2004 Bengali-English film Bow Barracks Forever, are beautiful tributes to Calcutta’s Christian culture.

Walk south from Bow Barracks and you will find New Market overflowing with Christmas stalls. Baubles, tinsel, Santa caps, plastic trees, sprays of fake snow. Flurys, Mocambo, Peter Cat, Trincas—all the old Park Street institutions of great dining—do roaring business with festive dinners and live music nights through Christmas and New Year. Do try the chicken patties at Flurys, with their classic Darjeeling tea to wash it down. Don’t miss the chelo kebab at Peter Cat, Chicken a la Kiev at Mocambo, or the Chicken Stroganoff at Trincas. On days I am confused, I head to Tung Fong in Park Street for a classic Calcutta-Chinese dinner.

But what moves me most, even now, is how completely Calcutta has made Christmas its own. Hindu homes put up stars on balconies, Muslim neighbours drop by with cake. Some still call it Boro Din, some don’t, but everyone celebrates—a kind of casual inclusivity that is hard to find now. Even after all these years and all those winters elsewhere, this is the one I come home to in my head. This is where I enjoy my long walks into oblivion with warm poetry and blossoming love in the evening air. This is where I find Anjan Dutt’s El Dorado.

*****

Dipanjan Sinha is a writer and editor who has been walking cities for over a decade finding stories about politics, culture and everything life.

souk picks

souk picks