A Mughal style guide to fine drinking

Editor’s Note: Contrary to current stereotypes, the Mughal emperors—while devout Muslims—enjoyed a glass of fine wine, especially when served in gorgeous bejewelled cups. They lived large and enjoyed life. Wine cups, no wonder, make appearances in all kinds of art from that era. Here, we try to understand the relationship between the Mughals and the culture of wine-drinking.

This article originally appeared on the MAP Academy website. All images that appear with the MAP Academy articles are sourced from various collections around the world, and due image credits can be found on the original article on the MAP Academy website. The MAP Academy is a non-profit online educational platform committed to building equitable resources for the study of art histories from South Asia.

-

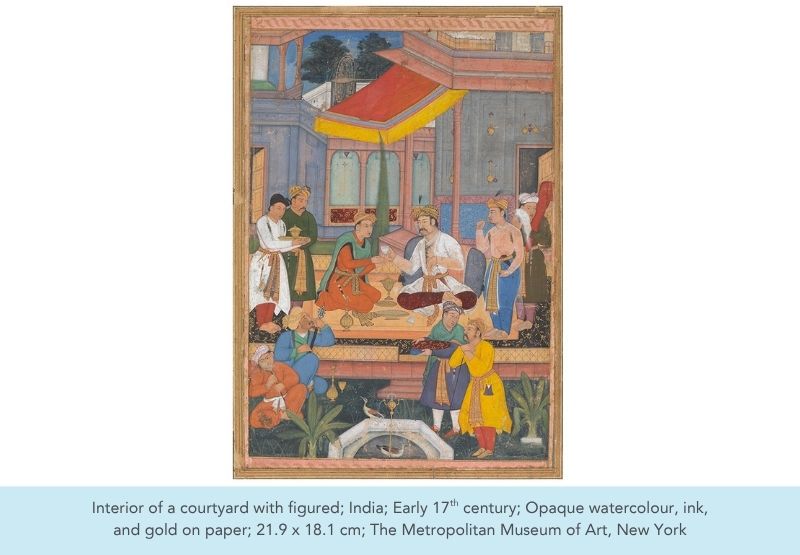

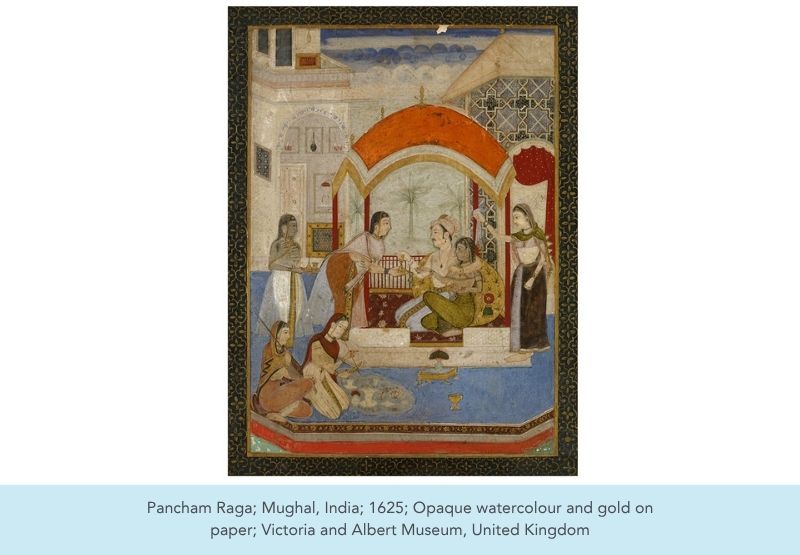

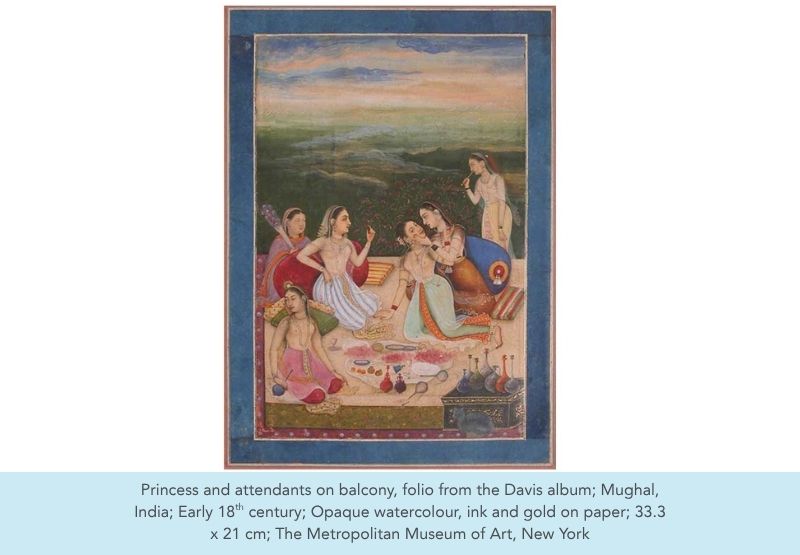

Although prohibited by the injunctions of the Quran and other juridical and religious Islamic texts, wine-drinking and the patronage of finely crafted wine cups was an important part of the courtly cultures of Mughal and other pre-modern Muslim societies. Most rulers of the Mughal dynasty (1526–1858) have been recorded in visual sources as participating in royal feasts and garden parties with a gold, silver or jade wine cup in their hands. Praise of wine also permeates Persian and Sufi literary traditions — which heavily influenced Mughal courtly culture — where it goes beyond the domain of pleasure to represent the ecstasy for love and union with God.

This abundance of wine-related imagery in Mughal visual and literary culture, along with the ornamentation of wine cups belonging to Mughal emperors, points to the symbolic significance of the wine cup motif, which often went beyond the object’s utilitarian function in Mughal South Asia.

The wine cup appeared not only in paintings depicting royal fetes and parties but also in those which showed the emperor and princes visiting saints and ascetics. Wine cups even appear in Mughal emperor Jahangir’s coins and jharoka portraits — formal square or rectangular portraits which show the emperor’s bust framed by a window, representing the darshan, or daily ritual of revealing himself to his subjects — indicating the association of the motif with the legitimacy of his kingship and near-divinity.

The wine cup appeared not only in paintings depicting royal fetes and parties but also in those which showed the emperor and princes visiting saints and ascetics. Wine cups even appear in Mughal emperor Jahangir’s coins and jharoka portraits — formal square or rectangular portraits which show the emperor’s bust framed by a window, representing the darshan, or daily ritual of revealing himself to his subjects — indicating the association of the motif with the legitimacy of his kingship and near-divinity.

Scholars suggest that this is probably because the wine cup in Persian literature often alludes to the magical cup of Jamshid, a mythological king from the Shahnama whose reign inaugurated the first golden age in Iranian history, which when filled with wine became a vessel of revelation: allowing him to see all the regions of the world as well as everything that happened there in the past and future.

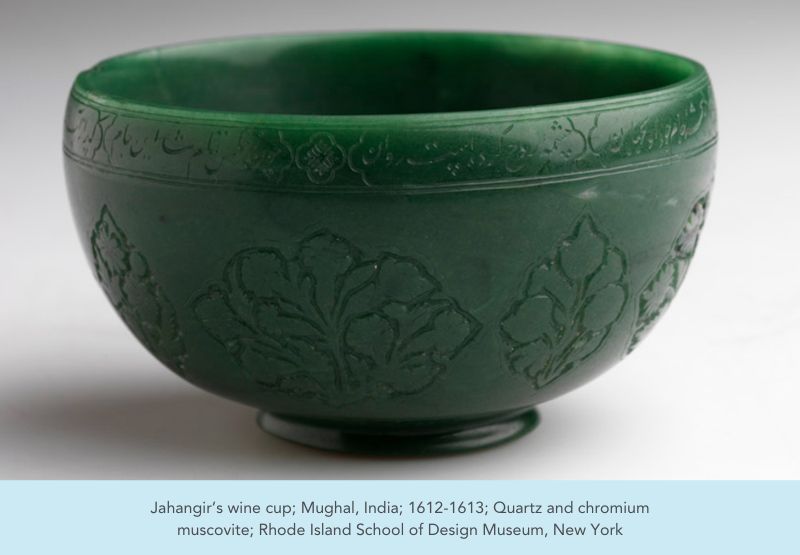

Patronised particularly by emperors Jahangir and Shah Jahan, Mughal wine cups are ornate objects, often engraved with verses and images and made of precious materials such as gold, emerald and jade, sourced from Khotan and Kashgar in present-day Xinjiang, China. They are usually small in size, ranging from about 3–17 centimetres in height and 3–35 centimetres in width.

Patronised particularly by emperors Jahangir and Shah Jahan, Mughal wine cups are ornate objects, often engraved with verses and images and made of precious materials such as gold, emerald and jade, sourced from Khotan and Kashgar in present-day Xinjiang, China. They are usually small in size, ranging from about 3–17 centimetres in height and 3–35 centimetres in width.

Of these, the jade wine cups — preferred by emperor Jahangir who is rumoured to have owned 500 of them — make for especially interesting examples. They display unusual forms, such as those of gourds and plum blossoms, and range in colour from glassy whites to light and dark greens. Moreover, almost all extant examples of Mughal wine cups are inscribed with dates, Persian verses praising wine, names of patrons and their honorifics, or are engraved with floral patterns.

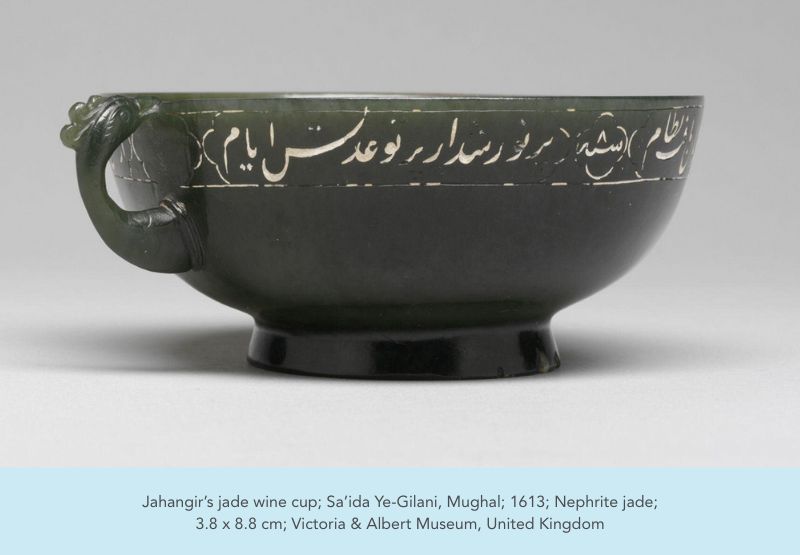

Among the large number of Mughal wine cups housed in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) in London is a shallow dark green vessel 3.8 centimetres high and 8.8 centimetres wide, made of nephrite jade and dated to 1613. It has a handle shaped like a cockerel’s head and Persian verses, filled in with white pigment, inscribed across its rim. The date of manufacture — 1022 AH, corresponding to Jahangir’s eighth regnal year — is placed inside a quatrefoil motif within the inscription.

Among the large number of Mughal wine cups housed in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) in London is a shallow dark green vessel 3.8 centimetres high and 8.8 centimetres wide, made of nephrite jade and dated to 1613. It has a handle shaped like a cockerel’s head and Persian verses, filled in with white pigment, inscribed across its rim. The date of manufacture — 1022 AH, corresponding to Jahangir’s eighth regnal year — is placed inside a quatrefoil motif within the inscription.

It also carries a quatrain which roughly translates to:

It also carries a quatrain which roughly translates to:

“Through the world-conquering Shah, the world found order/ our time became filled with light by the radiance of his justice/ From the reflection of his spinel-coloured wine may/ The jade cup be forever like a ruby.”

The verses indicate that the likely maker of this jade wine cup was Sa’ida-ye Gilani, a master craftsman and calligrapher from Iran, who was the zargar bashi (head jeweller) of Jahangir’s court.

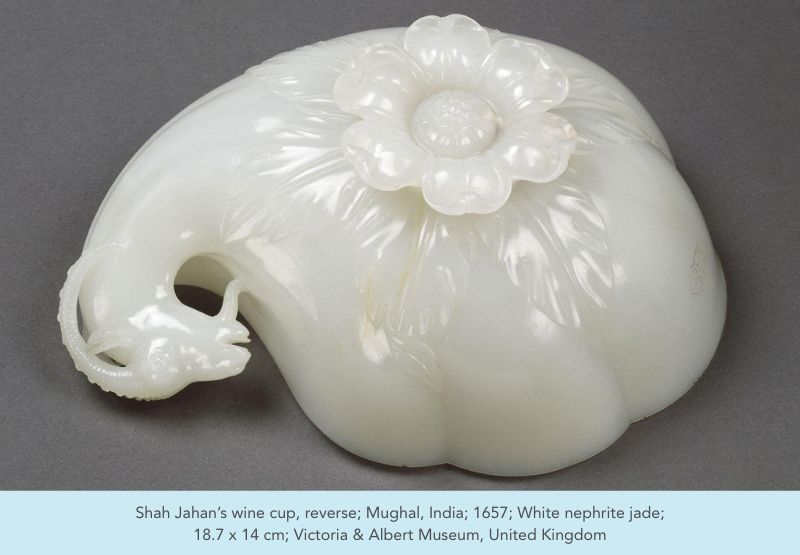

Another wine cup in the collection of the V&A Museum, dated to 1657, was probably crafted for emperor Shah Jahan. It is made of white nephrite jade and shaped like a gourd with a ram-head handle. The underside of the cup has a supporting base in the form of a lotus flower flanked radially by extending acanthus leaves.

Reflective of the cultural cosmopolitanism that characterised Mughal visual culture, the wine cup combines Indic, Chinese as well as European influences into its visual language. The ram-head handle and the lotus base are clearly elements borrowed from Hindu art, the gourd body is borrowed from Chinese models and the acanthus leaves show the influence of European art introduced through the prints and paintings brought by Jesuit missionaries to the Mughal court. However, despite this iconographic polyvalence, the artist manages to lend a stylistic unity to the wine cup, considered a hallmark of the arts of the Mughal court.

Reflective of the cultural cosmopolitanism that characterised Mughal visual culture, the wine cup combines Indic, Chinese as well as European influences into its visual language. The ram-head handle and the lotus base are clearly elements borrowed from Hindu art, the gourd body is borrowed from Chinese models and the acanthus leaves show the influence of European art introduced through the prints and paintings brought by Jesuit missionaries to the Mughal court. However, despite this iconographic polyvalence, the artist manages to lend a stylistic unity to the wine cup, considered a hallmark of the arts of the Mughal court.

Today, aside from the V&A, Mughal wine cups are housed in museum collections across the world, including eminent institutions such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, RISD Museum and Brooklyn Museum. Some, such as a large hexagonal emerald wine cup belonging to Jahangir, have also been auctioned off by leading auction houses like Christie’s. A beautifully carved white jade wine cup, adorned with creepers and grape leaves was acquired by the Bharat Kala Bhavan museum in Banaras Hindu University in 1962 and is one of the most distinctive objects in the institution’s collection.

Today, aside from the V&A, Mughal wine cups are housed in museum collections across the world, including eminent institutions such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, RISD Museum and Brooklyn Museum. Some, such as a large hexagonal emerald wine cup belonging to Jahangir, have also been auctioned off by leading auction houses like Christie’s. A beautifully carved white jade wine cup, adorned with creepers and grape leaves was acquired by the Bharat Kala Bhavan museum in Banaras Hindu University in 1962 and is one of the most distinctive objects in the institution’s collection.

–

The MAP of Knowledge

Sign up for the MAP Academy's free online course, Modern & Contemporary Indian Art, authored by Dr Beth Citron and developed in partnership with Terrain.art. Through engaging videos, illustrated texts and interactive quizzes, the course introduces a range of artists such as Amrita Sher-Gil, Zarina Hashmi and Sudhir Patwardhan, and explores a trajectory of key figures, artworks and pivotal moments in modern history. Spanning the late-19th century to the present day, it also examines artistic responses to several shifting socio-political forces of the time.

This article has been written by the research and editorial team at the MAP Academy. Through its free knowledge resources—Encyclopedia of Art, Online Courses, and Stories—the MAP Academy encourages knowledge building and engagement with the region's visual arts. Follow them on Instagram to learn more about art histories from South Asia.

souk picks

souk picks