Monet and the art of Impressionism: A guide

Editor’s note: Since so many of you love learning about art—or just looking at it—we’re continuing our series of art guides: visual essays that introduce you to an artist or style or school of art. In this one, our assistant editor Mekhala Singhal walks us through the joyous self-expressions of Impressionism, via the works of the great Claude Monet. Through some of the most important—and breathtaking!—paintings in history, learn about this early Modernist movement that went on to redefine art forever.

Written by: Mekhala Singhal

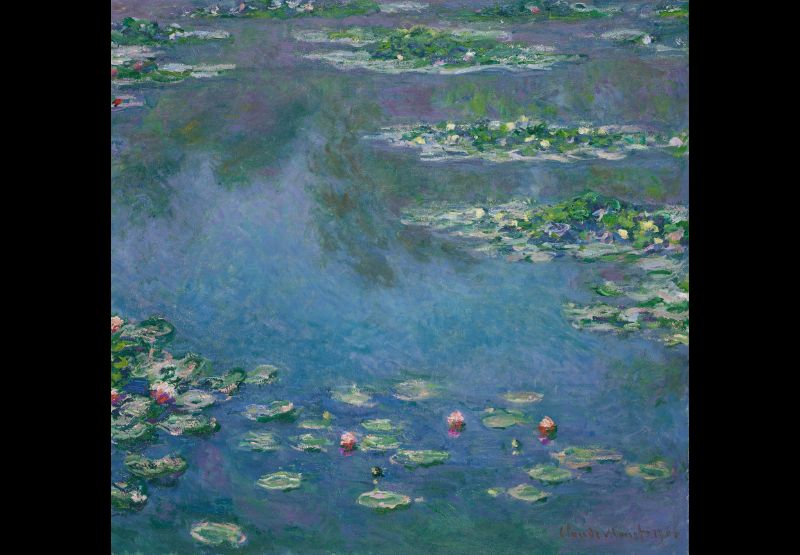

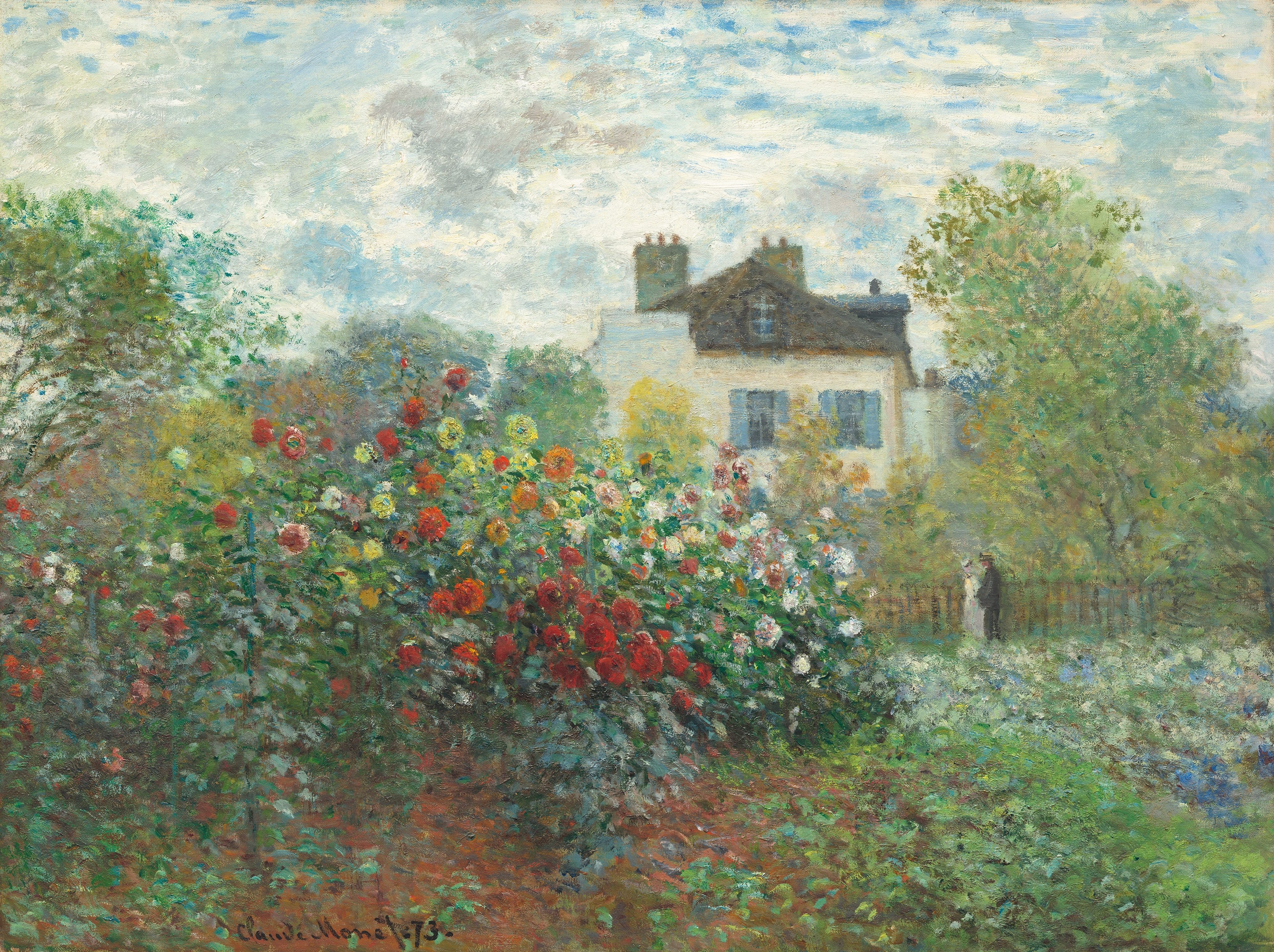

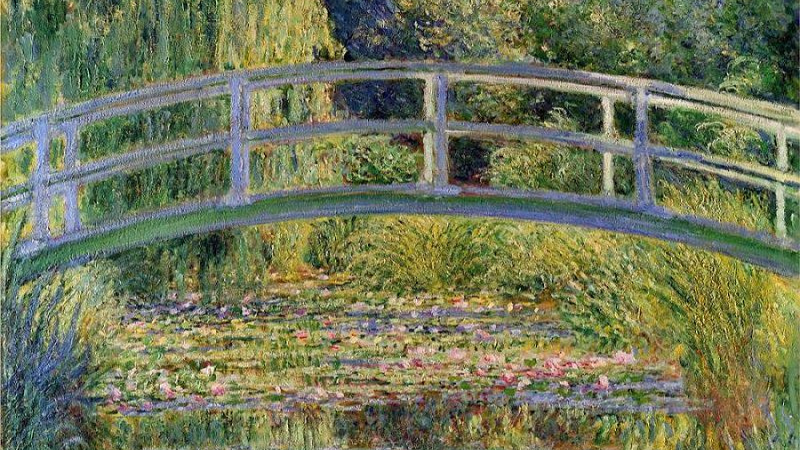

‘The Water Lilies’, arguably one of the most famous paintings of all time (pictured below), was the work of the great Claude Monet. The French Impressionist painter was born almost 200 years ago, on November 14, 1840. Monet began as a caricaturist, but was introduced to painting early, particularly to landscape painting, also known as ‘en plein air’ (French for ‘in the open air’) painting.

Impressionism

But what is Impressionism exactly? And why do so many people seem to love it so much?

Impressionism was one of the most important contributions made to art in the 19th century by the west. Perhaps what made Impressionism popular, especially after the Franco-Prussian war (1870–1871), was that the form was not tied to any religious imagery or faith. Through this new style of art, nature and people’s daily lives were taking precedence over portraiture and detailed figures.

Or perhaps it was something far more visceral: the bright colours and short brushstrokes that made the art feel alive. This is especially true in Monet’s work; you can see the wind blowing through the painted leaves. You can feel the rays of the sun falling on the surface of the lake.

While Monet is certainly the most famous of all the Impressionists, he isn’t the first. That honour belongs to Édouard Manet, who set out to paint subjects from his own time, rather than focussing on the past or mythological storytelling.

The most popular (and most scandalous) of his paintings may well be ‘Olympia’ (see below), sparking controversy not for being a nude, but for the confrontational gaze of the subject, and the implication that she might be a courtesan being venerated with flowers, painted in an ‘unsophisticated’ style.

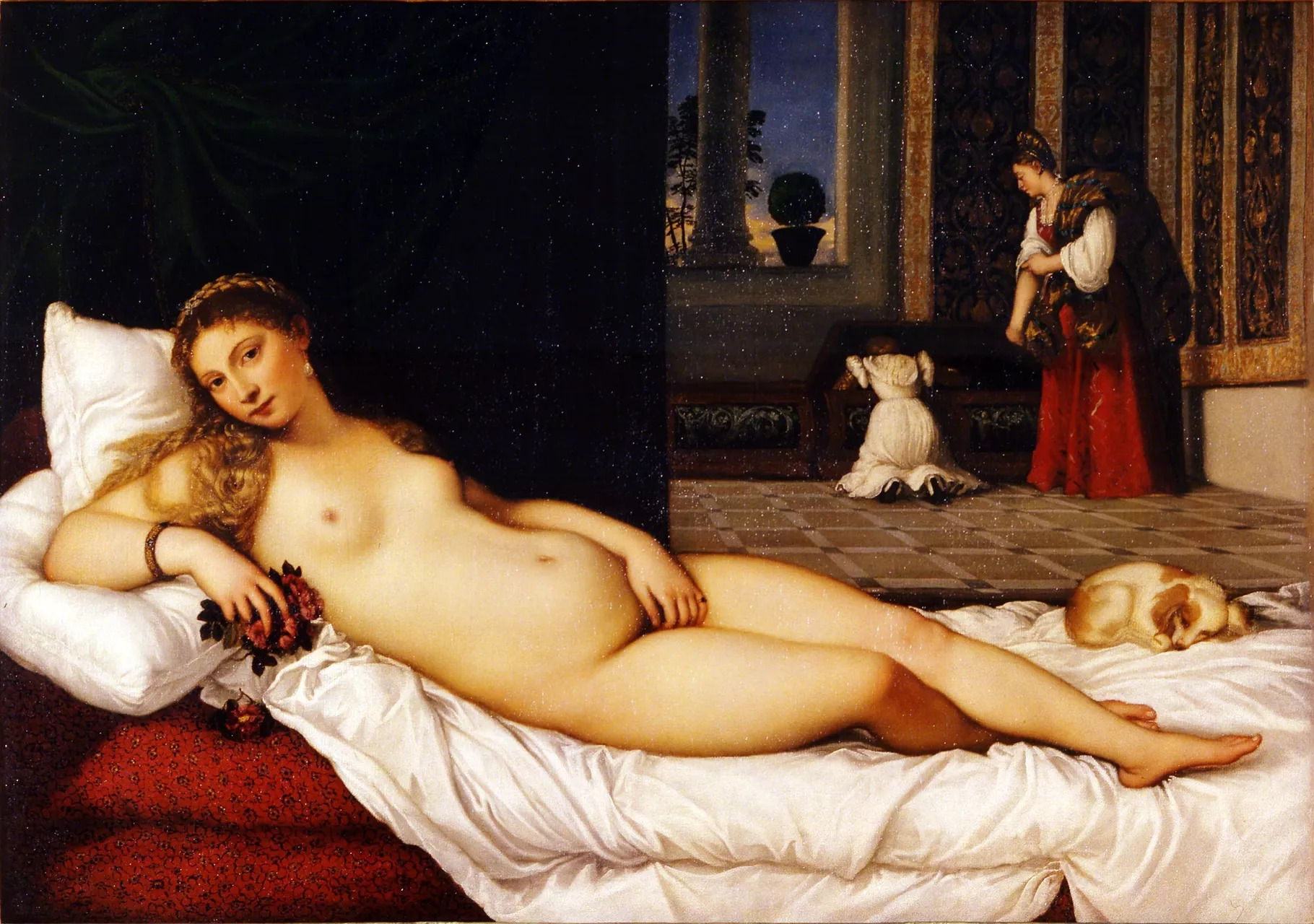

Does this painting look a little too familiar to you? Like you may have seen something like it before? You might be thinking of Italian painter Titian’s ‘Venus of Urbino’ (pictured below) which ‘Olympia’ was inspired by.

Does this painting look a little too familiar to you? Like you may have seen something like it before? You might be thinking of Italian painter Titian’s ‘Venus of Urbino’ (pictured below) which ‘Olympia’ was inspired by.

While stylistically diverse, the central focus of Impressionism was all about the real, daily lives of people.

While stylistically diverse, the central focus of Impressionism was all about the real, daily lives of people.

Impressionist paintings were known for their softness of colour and the interaction between light and shadow. These dynamics made the subjects of the paintings feel almost real. Artists had traditionally painted subjects as study, focusing on representing the aristocracy, or in depicting mythological characters. This new style allowed them to move away from that; now, they could paint life, as it happened. It was a way to express themselves.

By abandoning the traditional (and rather dull, if one may say so) palettes, the Impressionists were performing a radical act of defiance, not just by shocking everyone with the brightness of their paintings, but by actively going against the grain.

Over the course of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Impressionism grew larger and larger. There are artists whose work stand out even today, such as Mary Cassatt, Paul Cézanne, Edgar Degas, Camille Pissarro, Pierre-Auguste Renoir; the list goes on.

Many artists, including Monet, were indeed concerned with plein-air or outdoor painting. But plenty of other Impressionists would feature subjects from their daily lives—dancers, as in Degas’s work (pictured below), or the privileged classes, as in Cassatt’s paintings.

Many artists, including Monet, were indeed concerned with plein-air or outdoor painting. But plenty of other Impressionists would feature subjects from their daily lives—dancers, as in Degas’s work (pictured below), or the privileged classes, as in Cassatt’s paintings.

Fun fact

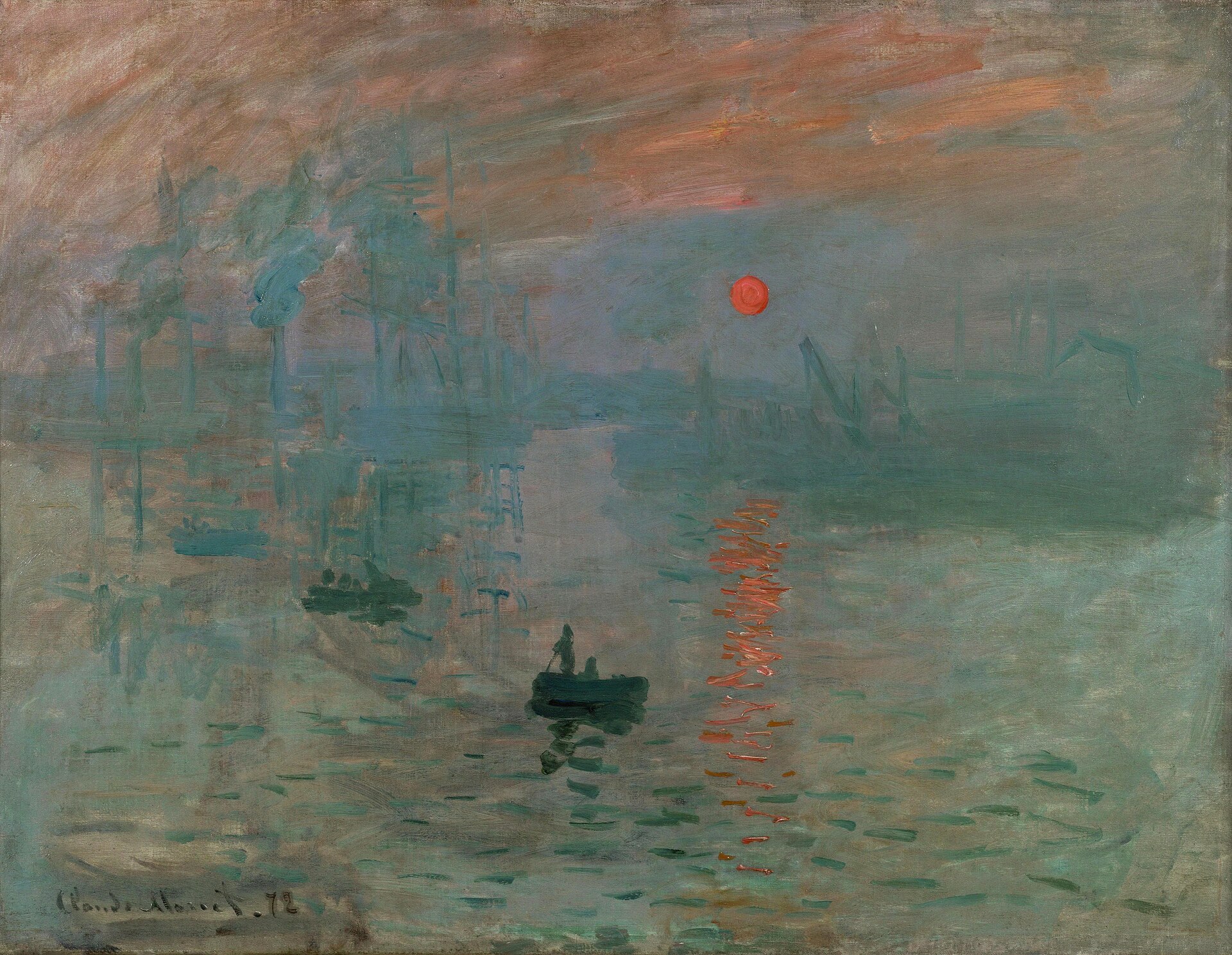

Impressionism gets its name from a painting of Monet’s, titled ‘Impression, Sunrise,’ (see below) which—in a tale as old as time—was received by critics with derision and hostility when it was first exhibited.

The Salon of the Refuseds: How the Impressionists came to life

The Paris Salons were public art exhibitions, financed first by the monarchy and then by the French government. In the 19th century, it was an annual event offering artists commissions to exhibit their work. However, the jury remained traditional and preferred conventional (even conservative) subject matter.

In the 1860s, Monet (and several friends) were rejected by the Paris Salon. These artists, in response, formed the Salon des Refusés—literally, the ‘Salon of the Refuseds’—in 1863. This exhibition featured artists who were rejected from the Paris Salon, and displayed Manet’s ‘Le déjeuner sur l’herbe’ (see below).

Fun Fact

The phrase ‘salon-style’ comes from the way art was exhibited as part of the Paris Salon (i.e., floor-to-ceiling installations).

The paintings in the Salon des Refusés received extreme criticism and ridicule, but this moment set forth and legitimised a movement of painters and artists who were otherwise facing absolute rejection.

Pleas for a second Salon des Refusés were ignored in the following years, once it was understood that mobilising and energising the avant-garde and experimental art world was a threat to the traditional values of the nation.

In 1873, frustrated by the continual rejection, Monet, along with other Impressionists, including Pissarro and Renoir, founded the Cooperative and Anonymous Association of Painters, Sculptors, and Engravers. They organised the first exhibition of Impressionist work in 1874, with over 150 pieces displayed. This is where ‘Impression, Sunrise’ was first exhibited.

While the show was certainly no Paris Salon, those who visited understood what the artists were trying to depict—the reality of a postwar life. This, many claim, is why Impressionism grew in popularity; it reflected the change that the nation and its people were undergoing, and forced the viewer to contend with said change.

Who was Claude Monet?

Claude Monet was a prolific artist. This is not an overstatement. He dedicated his life to making art—his ‘Water Lilies’ series alone consisted of approximately 250 oil paintings.

Monet was also a bit of a diva. Or—let’s be generous here—a very meticulous painter. His practice and method was unique and structured. For instance, if the light changed as the day went on, he’d stop painting. He would insist on returning the next day at the exact same time to the exact same spot, to catch the light the same way.

He is also known for the way his paintings depict air. That might sound strange at first, but in much of the writing about Monet, it is his ‘aerial’ effect that’s often highlighted.

The paintings give the impression (see?) that you may as well be standing by the water, body swaying gently with the wind as leaves rustle around you.

Monet was not universally loved in his time. As we now know, at the start of his career, he (along with Impressionism as a genre) was heavily criticised for his choices and his style, by both peers and patrons. Experimentation was not commonly encouraged in painters, and breaking the rules was considered sacrilegious. But he grew in popularity towards the latter part of the 19th century, and you cannot speak of Impressionism today without speaking of Monet.

Monet was not universally loved in his time. As we now know, at the start of his career, he (along with Impressionism as a genre) was heavily criticised for his choices and his style, by both peers and patrons. Experimentation was not commonly encouraged in painters, and breaking the rules was considered sacrilegious. But he grew in popularity towards the latter part of the 19th century, and you cannot speak of Impressionism today without speaking of Monet.

Fun fact

Monet was also a horticulturalist—some of the land you see in his paintings was land he owned and used to garden in. The 30 years he spent painting his water lilies were spent watching them in his own backyard.

Impressionism in India

In India, at the same time, while many students of art were studying the movements abroad, Impressionism hadn’t really made its way into the mainstream. However, by the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Indian artists such as KCS Paniker and Jamini Roy (before he turned to traditional Bengali folk art) began to paint the outdoors and shift the focus away from literalism. Indian artists, around this period, were getting exposed to European art styles thanks to the influence of the British here.

The most prominent Indian Impressionist was probably Jehangir Sabavala, influenced by the Modernists and inspired specifically by Impressionism. Sabavala—who practiced in the mid-to-late 1900s—ended up creating a style of his own by combining the Modernist technique and outline with a more surrealist, Impressionistic style.

The most prominent Indian Impressionist was probably Jehangir Sabavala, influenced by the Modernists and inspired specifically by Impressionism. Sabavala—who practiced in the mid-to-late 1900s—ended up creating a style of his own by combining the Modernist technique and outline with a more surrealist, Impressionistic style.

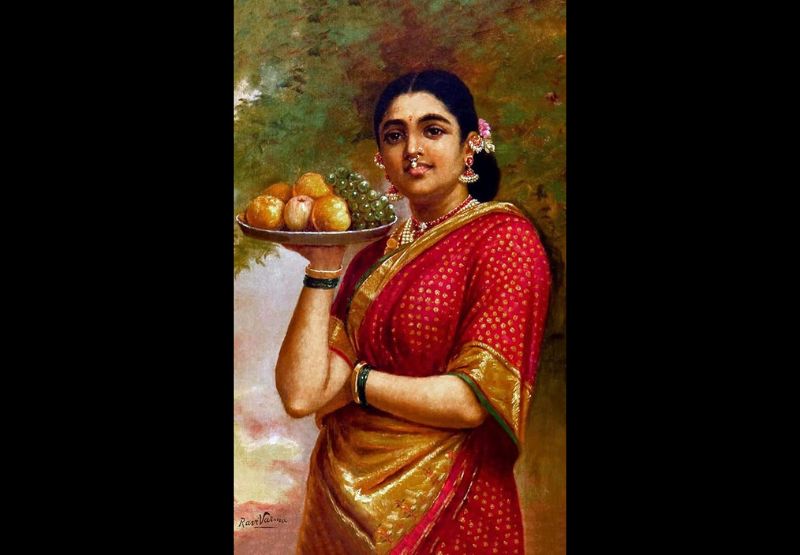

Impressionism, once it entered the country, left its mark. Artists began to embed the form into the techniques and styles they would use. Take Raja Ravi Verma for example (you can read an article we featured about him here). His paintings make use of Impressionistic methods—short brushstrokes; the way he plays with light and shadow; the diffused outlines of the subjects.

In a way, European Impressionism only really influenced Indian art via method and technique. But both the advent of Impressionism in Europe and the embracing of it in India were made possible by the changing tides in political beliefs and public and urban life. In France, the streets were being rebuilt post-war, and the population boomed in the 1870s and 1880s. In India, there was growing discontent with needing to adhere to tradition (particularly Western tradition) in the art world. If these were not the circumstances, perhaps the people may never have accepted Impressionism as a movement.

In a way, European Impressionism only really influenced Indian art via method and technique. But both the advent of Impressionism in Europe and the embracing of it in India were made possible by the changing tides in political beliefs and public and urban life. In France, the streets were being rebuilt post-war, and the population boomed in the 1870s and 1880s. In India, there was growing discontent with needing to adhere to tradition (particularly Western tradition) in the art world. If these were not the circumstances, perhaps the people may never have accepted Impressionism as a movement.

Why do we still love Monet?

Monet’s impact on modern art is massive. Although he received ample praise while he was alive, it took its time to arrive; but his unique vision, style, and body of work continues to be celebrated long after his death.

There is a sense of humanness that Monet’s paintings force you to confront. They make you feel compelled to step out into the real world, to look at the sky and the sunlight and the bright green of the grass outside.

There is a sense of humanness that Monet’s paintings force you to confront. They make you feel compelled to step out into the real world, to look at the sky and the sunlight and the bright green of the grass outside.

By embracing space as a character, and depicting leisure so openly and with such purpose, Monet and the other Impressionists insisted on the act of painting as one of joy, rather than one of simply creating. Moving away from tradition in order to allow imagination and feeling to thrive, the Impressionists built a language that is still used by artists today.

souk picks

souk picks