Rashomon is 75, its fears timeless

Editor’s note: Japanese master Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon was released 75 years ago. The film has endured aesthetically, philosophically, and socially for its immaculate craftsmanship and haunting themes. Outside of cinephilia, it led to the popular phrase 'The Rashmon Effect', signifying truth is subjective, a belief that has had horrible effects on our polity over the last 30 years. Today, we look back on what makes Rashomon an enigmatic classic that inspires and warns in equal measure.

Written by: Devarsi Ghosh

At 75, Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon feels like a warning from the future. The Japanese master’s most popular film, it is what can be accurately called a philosophical thriller insofar as its mystery keeps you on the edge of your seat; and its themes continue to resonate three-quarters of a century later. More than that, Rashomon holds up aesthetically as an intensely contemporary film. Cut to the bone by editor Shigeo Nishida, the film’s 88-minute runtime is throbbing with menace and despair.

Rashomon, set in the Heian era (794-1185), opens with two individuals escaping a storm by taking shelter under the ruined Rashomon gate in the borders of Kyoto. The woodcutter and the priest are shaken from having witnessed the trial of a samurai’s murder. Conflicting accounts emerged from eyewitnesses, including the woodcutter, the samurai’s wife, the bandit who allegedly murdered her husband, and the samurai’s spirit sharing his bit via a medium.

Each person’s version is carefully structured to protect their idea of themselves. The bandit Tajomaru (Japanese icon and Kurosawa’s favourite, Toshiro Mifune) spins a yarn where his machismo takes centrestage. The samurai’s wife has a story where she is an innocent victim. The samurai’s spirit claims his wife is disloyal while the bandit is a man of honour.

The priest is bothered that there is no one single truth, and no one can be trusted. He observes, “Most of the time we can’t even be honest with ourselves. It’s because men are weak that they lie, even to themselves.”

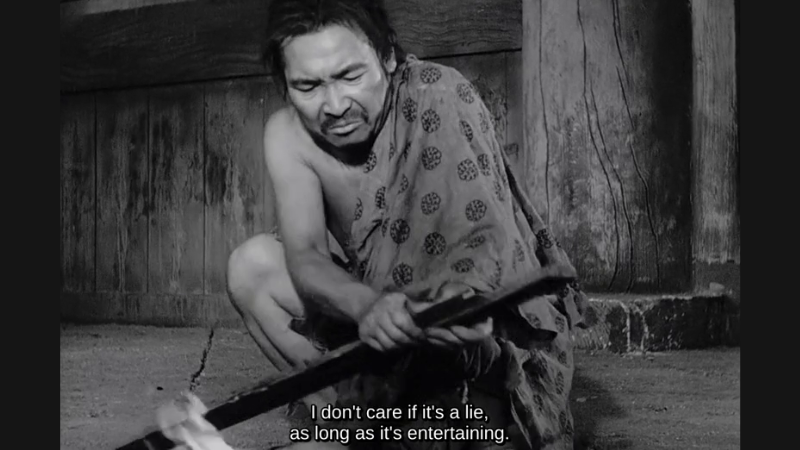

Meanwhile, a particularly cynical commoner joins them. He listens to the priest and the woodcutter’s stories and seems to be sticking around just to entertain himself. Their conversation acts as a Socratic dialogue trying to make sense of what actually went down between the samurai, his wife, and the bandit—and what it says about humanity.

Kurosawa and co-writer Shinobu Hashimoto spun Rashomon out of Ryunosuke Akutagawa’s short stories ‘In a Grove’ and ‘Rashomon’. The former lends Kurosawa’s film the structure. ‘In the Grove’ follows the murder trial of the samurai seen through the eyes of various characters. The latter gives the film its spiritual charge: can humans be good and trustworthy in the worst of times?

Note the dystopian setting in Akutagawa’s short story.

“For the past few years, the city of Kyoto had been visited by a series of calamities, earthquakes, whirlwinds, and fires, and Kyoto had been greatly devastated. Old chronicles say that broken pieces of Buddhist images and other Buddhist objects, with their lacquer, gold, or silver leaf worn off, were heaped up on roadsides to be sold as firewood. Such being the state of affairs in Kyoto, the repair of the Rashomon was out of the question. Taking advantage of the devastation, foxes and other wild animals made their dens in the ruins of the gate, and thieves and robbers found a home there too. Eventually it became customary to bring unclaimed corpses to this gate and abandon them. After dark it was so ghostly that no one dared approach.”

The Rashomon gate is a metaphor for a society in ruins, where three individuals are coming to terms with what even can be believed in the end of days. No wonder then that Kurosawa's film has gained relevance over time in the era of post-truth politics.

American anthropologist Karl G Heider first used the phrase “The Rashomon Effect” in an essay of the same name in 1988. He borrowed the film’s name to highlight the subjectivity of interpretation with regard to various ethnographers bringing conflicting accounts while studying the same communities.

American anthropologist Karl G Heider first used the phrase “The Rashomon Effect” in an essay of the same name in 1988. He borrowed the film’s name to highlight the subjectivity of interpretation with regard to various ethnographers bringing conflicting accounts while studying the same communities.

Four years later, playwright and novelist Steve Tesich introduced the word “post-truth” in the mediasphere. In a 1992 essay about recent American political scandals, called ‘A Government of Lies’, Tesich observed that politicians had stopped bothering to be accountable because the public appeared to be willing to be deceived if they felt comforted by their leaders’ lies. Tesich called this a post-truth world.

Tesich wrote: “We are rapidly becoming prototypes of a people that totalitarian monsters could only drool about in their dreams. All the dictators up to now have had to work hard at suppressing the truth. We, by our actions, are saying that this is no longer necessary, that we have acquired a spiritual mechanism that can denude truth of any significance. In a very fundamental way we, as a free people, have freely decided that we want to live in some post-truth world.”

Remember what the commoner said in Rashomon? “I don’t care if it’s a lie as long as it’s entertaining.”

With corruption and malgovernance, not only does the Rashomon gate, an emblem of the kingdom, fall apart, but also the basic premises on which society is formed, such as a consensus on what is truth itself. Kurosawa took a jigsaw puzzle of a murder mystery, wrapped it in a doomsday enigma, and created a nuclear bomb whose half life has continued to stretch into the era of Trump, Modi, Erdogan and Putin.

There is still no definitive version of what really went down militarily between India and Pakistan in May. For the longest time, global news media, politicians and thought leaders were puzzled over whether to call what is happening in Gaza a genocide. Or how about the way Sushant Singh Rajput’s death was processed by the news media and our citizens? Today, we are sealed in our individual silos, our algorithms feeding us views and news exclusively tailored to comfort us with our understanding of truth. Unfortunately, this is not a Kurosawa film that will end at 90 minutes.

And yet, Kurosawa, the master, finds a neat way to end such a pessimistic story. He crafts a new version of the samurai’s death, separate from Akutagawa’s story, which is a beautiful and complex distillation of the film’s sharp gender politics. This version, finally shared by the woodcutter, shows that there is a strong speck of resistance running in Kurosawa’s film.

And yet, Kurosawa, the master, finds a neat way to end such a pessimistic story. He crafts a new version of the samurai’s death, separate from Akutagawa’s story, which is a beautiful and complex distillation of the film’s sharp gender politics. This version, finally shared by the woodcutter, shows that there is a strong speck of resistance running in Kurosawa’s film.

Rashomon ends with the cries of an infant abandoned at the Rashomon gate. Like we see in contemporary dystopian science-fiction like Children of Men (2006) and Blade Runner 2049 (2017), it is the presence of a baby that sparks hope in the heart of man. The woodcutter, despite having six children he is struggling to feed, chooses to adopt this child. The priest realises, yes, there is still goodness possible, there is “indeed a crack in everything, that’s how the light gets in”.

Devarsi Ghosh is a film critic and Consultant Editor, Advisory.

souk picks

souk picks