Delights of Indian satire: A reading list

Editor’s note: Satire, irony, caricature, and parody are a long and storied tradition in Indian literature. In this reading list, writer Amritesh Mukherjee compiles ten great works of satire in Indian literature across centuries and generations. From the seminal Raag Darbari by Shrilal Shukla to Tharoor’s The Great Indian Novel or English, August by Upamanyu Chatterjee.

Written by: Amritesh Mukherjee

*****

Satire thrives in the gap between what a society claims to be and what it actually is. That gap, in India, is a canyon. And while Indian literature has long practiced this biting form of humour and social critique, it doesn’t always get recognised as such. When one thinks of Indian writing, the instinct is to conjure epics and mysticism, post-Independence trauma, Partition narratives. But rarely is the acidic satire written across languages and generations.

This year marks the 100th birth anniversary of Shrilal Shukla, whose Raag Darbari painted the machinery of rural Indian governance as a tragicomic opera. His work belongs to a larger tradition, which I’ve tried to capture here. The books on this list span Hindi, Urdu, Tamil, Odia, Bengali, Malayalam, Kannada, Marathi, and English. They take shots at bureaucrats and Brahmins, postcolonial elites and feudal landlords, arranged marriages and caste councils, power brokers and consumerist anxieties. When speaking plainly is dangerous or outright impossible, satire becomes a necessity to speak truth. The mirror that forces you to finally look.

Raag Darbari by Shrilal Shukla (1968), translated From Hindi by Gillian Wright

Few novels capture the gap between what India promised and what it delivered as ruthlessly as Raag Darbari. Shrilal Shukla's 1968 masterpiece drops Ranganath, an educated outsider, into Shivpalganj, a village where every institution, ostensibly meant to uplift, has been captured by local strongmen. His uncle Vaidyaji orchestrates this ecosystem—the college is a patronage fief, the panchayat a joke.

Shukla's satire uses caricature and ironic juxtaposition effectively, such as student politics entangled with patronage and petty criminality or villagers being told to “Grow More Grain” through posters. The machine—petty, procedural, never-ending, inescapable—meanwhile grinds on, crushing dignity under the weight of files and favours.

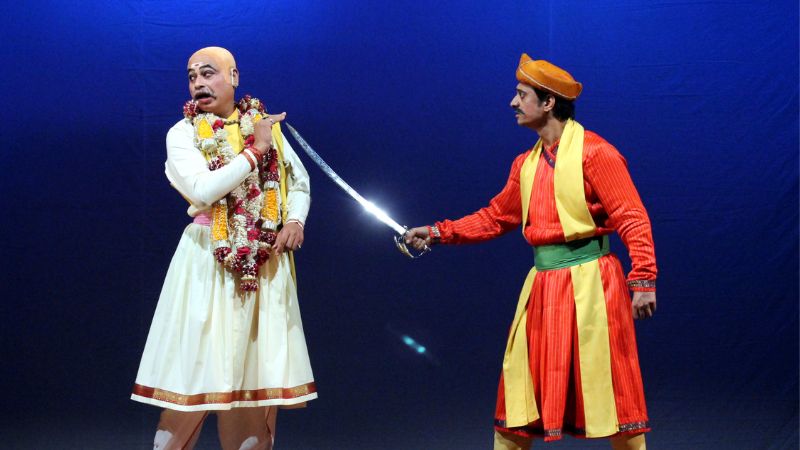

Ghashiram Kotwal by Vijay Tendulkar (1972), translated From Marathi by Jayant Karve and Eleanor Zelliot

Vijay Tendulkar's Ghashiram Kotwal premiered in 1972 and immediately drew protests and bans for its criticism of contemporary Maharashtrian politics and the police state. Set in 18th-century Pune under Peshwa rule, it follows Ghashiram, a humiliated Brahmin outsider who strikes a Faustian bargain with kingmaker Nana Phadnavis: access to his daughter in exchange for the post of kotwal.

Once installed as police chief, Ghashiram rules through petty terror—permits for everything, jails for nothing—until his excesses embarrass his patron and he's thrown to the crowd. The play indicts the ecosystem that manufactures its own monsters, with its folk-theatre grammar—tamasha, lavani—creating a communal experience.

Mr. Donkey’s Autobiography by Krishan Chander (1957), translated From Urdu by Helen H Bouman

Krishan Chander’s donkey-narrator wanders through post-Independence public life, using an animal fable to puncture civic and political hypocrisies. He moves from municipal offices and salons to newsrooms and political rallies, his plain speech colliding with pomp and flattery.

At times, he’s paraded by crowds, at others beaten and discarded, only to be celebrated again. Told in sharp, episodic sketches, the book turns perspective upside down as the “low” point of view becomes the moral high ground, so that the beast of burden is the only figure not performing “virtue”.

The Great Indian Novel by Shashi Tharoor (1989)

Can you retell the Mahabharata as a satire of Indian politics? Shashi Tharoor's answer is The Great Indian Novel, narrated by Ved Vyas as he dictates a "Song of Modern India" to Ganapathi. Eighteen books mirror the epic's structure, but the targets are contemporary, from party power games to the Emergency's authoritarian theatre.

Gandhi becomes Gangaji, Nehru the blind king, Jinnah a tragic Karna, Indira Gandhi a ruthless Priya Duryodhani. Epic cadences are grafted onto cabinet meetings, and mythic diction serves mundane politicking. Published in 1989, it punctures the sanctimony of official narratives by asking what "dharma" means when wielded by politicians.

Estuary by Perumal Murugan (2020), translated From Tamil by Nandini Krishnan

Perumal Murugan's Estuary, more than a loud satire, is a dry, needling irony about India's anxious middle class. Set in contemporary "Asurapur" (every character bears an asura-suffix name), the novel follows government clerk Kumarasurar as he spirals over his teenage son Meghas's demand for an expensive smartphone and a college choice the father distrusts.

The asura-naming device frames modern life as a low-grade hellscape of rules and temptations—coaching factories, surveillance-ish school regimes, office computerisation panic, consumerism as a moral yardstick. Murugan's first fully urban work, it shows the absurd textures of modern middle-class life à la "good college + good phone = good life".

Six Acres and a Third by Fakir Mohan Senapati (1896), Translated From Odia by Rabi Shankar Mishra, Satya P. Mohanty, Jatindra K. Nayak and Paul St.-Pierre

In a feudal society like ours, theft usually only requires a few sheets of stamped paper. Fakir Mohan Senapati's classic satire, Six Acres and a Third, set in rural Odisha in the 1830s, depicts a zamindar dispossessing a weaver couple using mortgages and the new colonial legal machinery.

The novel's satire is double-aimed: on one hand, it mocks colonial courts that let native elites plunder small holders; on the other, it ridicules those elites for weaponising "modern" legality against their own. Its wry, intrusive narrator mixes village idiom with learned asides, treating bonds and ledgers as comic props that make theft look proper.

The Observant Owl: Hutom’s Vignettes of Nineteenth-Century Calcutta by Kaliprasanna Sinha (1861-62), translated From Bengali by Swarup Ray

Kaliprasanna Sinha's The Observant Owl is a collection of quick sketches: 19th-century Calcutta rendered as cartoons. Published as Hutom Pyanchar Naksha in 1861-62, it recreates the city through its types—the classic babu itemising aristocratic affectations bought with Company-era money or priests and petty officials trading on ritual and authority.

Sinha's narrator, Hutom the owl, speaks in bawdy Bengali, skewering new money and colonial mimicry. The episodic novel, devoid of a larger plot, targets the social theatre of a city learning the manners of colonial modernity while clinging to old privileges.

English, August: An Indian Story by Upamanyu Chatterjee (1988)

Upamanyu Chatterjee's English, August (1988) is a deadpan send-up of India's bureaucratic theatre told from inside the machine. Agastya (“August”) Sen—privileged, bookish—arrives in the furnace-hot district town of Madna for his mandatory IAS training year.

He drifts through a carousel of meetings and files, skipping work and smoking pot, while reading Marcus Aurelius. The bone-dry satire reveals the performance of "public service," where governance is a mere ritual of presence. If the earlier picks mocked power from below, August ridicules it from within, capturing 1980s elite alienation and the existential joke of the state itself.

Bovine Bugles by Vadakkke Koottala Narayanankutty Nair (VKN), translated from Malayalam by the author (1969)

Bovine Bugles (Arohanam, 1969) is VKN’s high-brow political satire of India’s late-1960s power bazaar. The novel, translated into English by the author, reads like a dispatch from the corridors of power, where ideology is costume and careers are built on bluff. Our guide is Payyan, VKN’s recurring anti-hero, hustling upward through proximity to power.

With sharp register shifts and wordplay, from lofty oratory to street argot, the book shows how grand phrases hide petty ambition: slogans recur as gags, and speechifying stands in for statecraft. Power is staged in speeches and moral postures, with language as the glue that makes performance look like principle.

Ghachar Ghochar by Vivek Shanbhag (2013), translated from Kannada by Srinath Perur

Set in Bengaluru, Ghachar Ghochar follows an unnamed narrator whose family vaults from near-poverty to comfort. Money arrives first; morality scrambles after. In this spare, unsettling novella, family language does the dirty work: their private phrase “ghachar ghochar” (“tangled beyond repair”) becomes the book’s thesis.

With the narrator’s cool tone smoothing over chilling choices, ant infestations (and those tell-tale sugar trails) become emblems of bigger appetites. If earlier satirists mocked institutions, Ghachar Ghochar looks inward, at the family itself, capitalism's first classroom.

******

Amritesh Mukherjee is a reader, writer, and journalist—mostly in that order. Covering literature, cinema, and art through his writings, he’s fascinated by the stories that shape our world.

souk picks

souk picks