Azhar bhai ka paan, Lucknow ki shaan

Editor’s note: Every month we bring to you an article from our partner enthucutlet—a truly unique food magazine that brings you unusual stories, perspectives, and guides on food in India and beyond. The magazine is helmed by a brilliant team of editors and the good folks of Hunger Inc—the parent company of The Bombay Canteen, O Pedro, Bombay Sweet Shop, and Veronica’s.

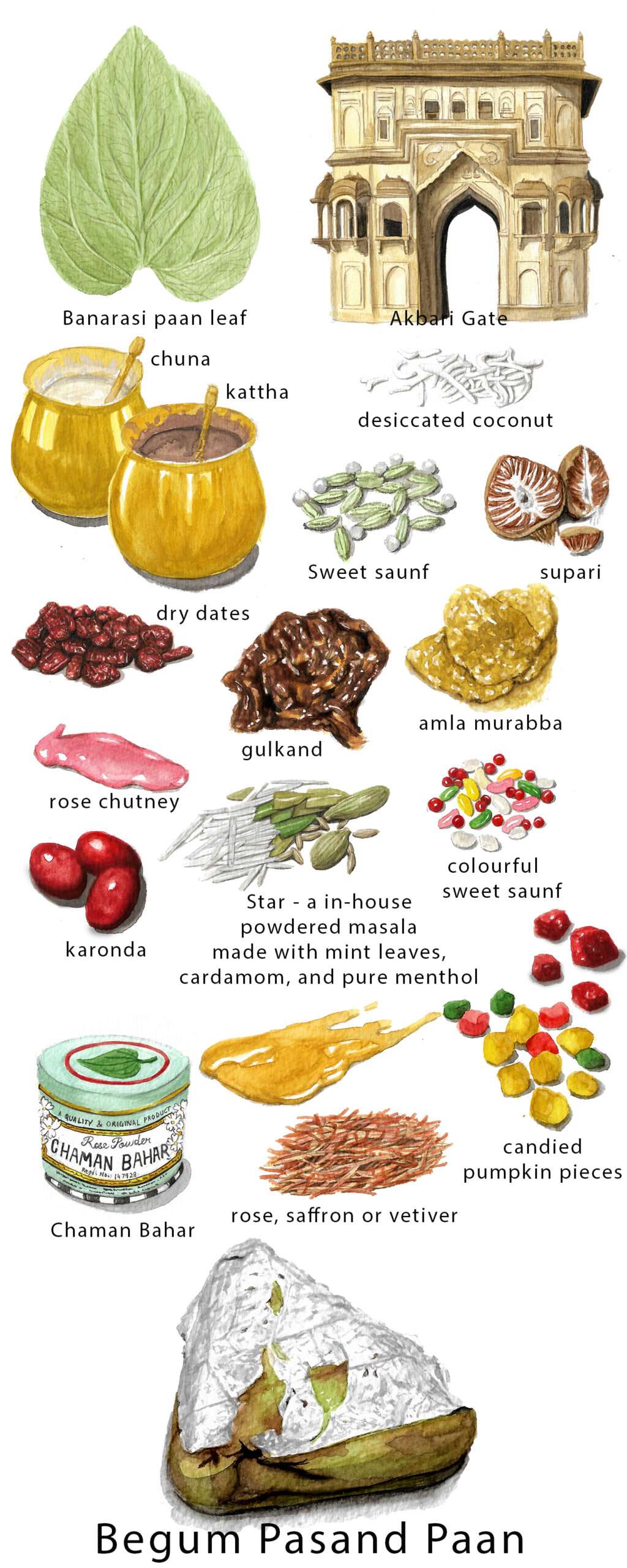

In this piece, Shirin Mehrotra takes us through the art and science of folding a paan in Akbari gate, Lucknow. The article includes a gorgeous illustration by Shawn D’souza.

Written by: Shirin Mehrotra is an independent writer and researcher. Her interests lie at the intersection of food, culture, and communities with a special focus on urban foodscapes and migration. Her work has appeared in Whetstone Magazine, The Juggernaut, Feminist Food Journal, and HT Brunch among others. You can follow her here.

At Azhar Bhai’s paan shop in Lucknow’s Akbari Gate, a large board announces that it is Lucknow ki Shaan, or the pride of Lucknow. Nestled amidst bustling kebab shops, and a sea of street vendors selling all sorts of knick-knacks in the city’s busiest area, this little paan ki gumti is easy to miss on an aimless stroll; but ask around and you will be pointed to it immediately.

The board also displays the varieties of paan on offer—there is Begum Pasand Paan: made with candies and sweeteners for the appeasement of the city’s erstwhile queens, and Nawab Wajid Ali Shah ki gilauri: fashioned after the flamboyant, indulgent nawab whose histories still shape the way Lucknow eats.

But the one that gets my attention is Palang Tod Paan, translating literally to ‘the paan that breaks the bed’.

The paan was created to increase the virility of men, Azhar Bhai says, and with a little cajoling, he elaborates its contents – pista, badam, akhrot, mushk or musk, zafran or saffron, and majun-e-khas, which is a unani formulation for male sexual disorders. “Suhaag raat ke liye”, he adds, shyly, on further prodding. “This one is for the wedding night”.

Azhar Bhai’s shop has been around for almost 80 years, since 1938. Azhar Bhai is 65 years old, and was 12 when started working at the shop as an apprentice, learning the art of folding paan from Naseem Sahab, the owner of another paan shop in Akbari gate. “Back then in 1970, the cost of four paan was one rupee,” he tells me, as his assistant Bahadur Shah Zafar (no relation with the last Mughal emperor) begins to prepare the paan. Bahadur Shah arranges two rows of paan leaves—the Desawari: a dark green one from Mahoba, Bundelkhand for the Wajid Ali Shah ki gilauri, and a pale yellowish green, which is famously known as Banarasi, for the Begum pasand paan.

The Desawari leaf was introduced in the Bundelkhand region in the 9th century by the Chandela kings. In their courts, beeda or paan quids were placed on a platter while challenging someone for a duel.

If the person picked up the quid, it meant that they accepted the challenge.The Desawari paan has large crunchy leaves, and a slightly bitter-sweet taste, while the Banarasi leaves are less bitter and melt instantly in the mouth.

As I watch the paan being prepared with all its elements in an assembly line, I also learn about the unique baking process of the Banarasi paan. In Paan Dariba, the wholesale market of paan leaves in Banaras, green leaves that come from different parts of the country (Banaras does not grow its own paan). There, they are stored in a furnace-like room where they are smoked for three-four days until they change colour. Paan Dariba hosts a variety of leaves—namely Jagannathi from Odisha, Desi from West Bengal and the most sought after—Maghai from Central Bihar. The baking process also changes the texture, as well as the taste, making the leaves less bitter. “Ye hunar Banaras walon ke haath mein hai” says Azhar bhai. “Baking paan this way is a special skill of the people of Banaras”.

But back to our paan here in Akbari Gate: I watch as Bahadur Shah spreads a layer of chuna (or slaked lime), and kattha (an extract of acacia trees), on the leaves for paan. This duo is responsible for the characteristic, deep red colour that emerges when paan is chewed. This is also the basic formula: the leaves, chuna and kattha, and from here, the process varies for different paan, Azhar Bhai says. In both, the Begum Pasand, and Wajid Ali Shah ki Gilauri, Azhar Bhai adds desiccated coconut followed by chopped and soaked supari; after which he adds a range of textures and flavours—sweet saunf, dried dates, gulkand, amla murabba, rose chutney, and star—an in-house powdered masala made with mint leaves, cardamom, and pure menthol.

Then there are the final additions: in the Gilauri—a smattering of majun-e-khas and a shahi goli (the contents of which are too precious to be disclosed) are added to make it a potent aphrodisiac. The ingredients for Begum Pasand, in turn, are colourful sweet saunf; condiments called cherry and karonda—both which are different shapes of candied pumpkin pieces; chaman bahar, and a chutney made with rose, saffron or vetiver to add sweetness for women customers.

In the Nawab ki Gilauri a delicate sheet of silver warq is placed on top before the paan is given its final fold while Begum Pasand is wrapped in warq after folding. The two paans taste starkly different from one another—the Begum Pasand is milder, sweeter and juicier while the Gilauri has a robust flavour of the leaf with a minty aftertaste.

For centuries, paan has been intrinsic to Lucknow’s tehzeeb,and associated with its spirit of mehman-nawazi or hospitality. Traditionally, paan was offered to the guests in the royal courts, at mushairas and kothas.The folding of a paan quid brought nazakat or elegance to gatherings, and the additions—of silver warq, clove to staple the paan, the spray of kewda on a folded paan—suggest that it’s an experience to be cherished at a slow and leisurely pace that match that of the city.

Azhar Bhai’s shop is a reminder of the city’s past, of Lucknow’s love for storytelling mixed with a bit of healthy teasing; and as I stand there talking to Azhar Bhai, his regular customers gather around – some listen to us talk, and most add their own two bits. I try to prod him once more to tell me the secret behind his Hajme ka Paan, or digestive paan, but he resists. Instead, pat comes a reply from one of the elderly customers, “Lucknow mein do log kabhi apna raaz nahi batayenge. Ek hai Tunday kababi aur ek Azhar miyan” he says, mentioning another of Lucknow’s culinary icons. “There are two people in Lucknow who will never spill their secrets, and those are Tunday kababi and Azhar miyan”.

Grab a bite of enthucutlet

enthucutlet: the food mag to come to for fun, unusual, and surprising stories about food in India (and sometimes beyond). Expect untold tales, actionable guides, cool desi food news, insider info, and lively events. Food intersects with everything; and we're here to explore it all, with you.

enthucutlet's tenth season comes as we celebrate two years of this wonderful magazine. And it is truly diverse in all its being. This is a season that has stories that refused to leave us, notes that brightened our inboxes over the past two years, stories we had to absolutely put out in the world.

Unlike our last nine seasons, ‘Season X’ has no themes. It is wide-ranging but equally binding. There's a story on paan, another on a writer's findings of fish meals in a desert, one that talks about India's fluid dining spaces revolving around community building, and one more where samosas are being compared to curry puffs.

And of course, to go with these delightful stories, we have enthuGuides — your eating itineraries. ‘Season X’ is waiting for you.

Head over to enthucutlet.com for a fresh drop of fun, delicious food and drink content.

To get first dibs on all things enthu, subscribe on our website, and follow us on @enthucutletmag on Instagram and Twitter.

enthucutlet is brought to you by the cutlets behind The Bombay Canteen, O Pedro, Bombay Sweet Shop, Veronica's, and Papa's.

souk picks

souk picks