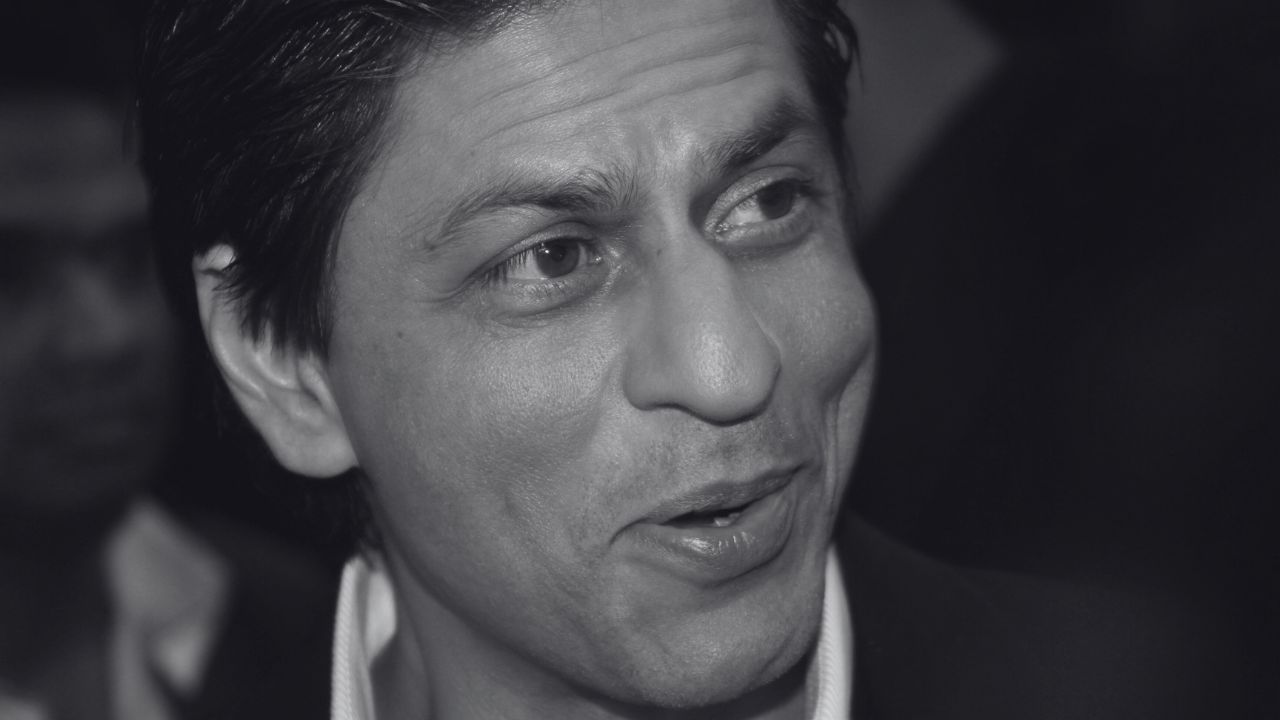

Kabhi comfort, kabhi (Shah Rukh) Khan

Editor’s note: As an actor, Shah Rukh Khan is more signifier than sex symbol—often a survival tool for Indian women in a damaging, violent culture of patriarchy. In this deeply personal essay, poet-author Manjiri Indurkar reveals her intimate relationship with a distant superstar—who came to be a kind voice in her head, first as a lonely, abused child and later as an adult struggling with trauma. It offers a moving look at how movies shape, save (sometimes damage) our inner selves.

Written by: Manjiri Indurkar. She is the author of It's All In Your Head, M and the poetry collection Origami Aai, both published by Westland. Her work has appeared in publications like the Indian Express, Mint, Firstpost, Himal, and National Herald, among others. When she's not writing for publications, she teaches her craft through her workshop, The Narrative Nook, and publishes her other pieces on her Substack, Unfixing The Map Pin.

*****

There’s a man who lives inside my head. His voice is kind, his demeanour patient, and his presence reassuring. Whenever I find myself jumping through loops of self-doubt and derision, his voice reminds me to breathe, not get ahead of myself, just stay in the moment. Hearing comforting things in his voice has helped me make sense of the world and of myself.

That man is Shah Rukh Khan. However, the road to finally finding a friend in Shah Rukh was, let’s say, hairy. Enter stage right: Anil Kapoor.

He was the answer my five-year-old self gave to people who asked me who my favourite actor was. Growing up in the ‘90s, with parents who were both working to ensure I got a great life, cinema was my quiet companion. The television had no parental lock. Censorship wasn’t a concept that had entered the vocabulary of my overworked parents. It just meant that I was “allowed” to watch anything and everything. And I did.

It was Mr India that made me love Anil Kapoor. He was the saviour of children, and I was a child in need of saving.

I watched all his films. One unfortunate afternoon, I watched a film I shouldn’t have. Benaam Badshah, where Anil Kapoor’s character rapes Juhi Chawla’s. It made no sense that the hero would do such a thing. I don’t know if five-year-olds are supposed to understand rape, but I did. It was, after all, an integral part of my life. Watching Mr India do that to someone changed my perception of the actor. And just like that, he wasn’t my favourite actor anymore.

There was a void, and Shah Rukh Khan would soon fill it. But if you ask me to point to that one moment when I fell in love with him, I can’t do it. He may have come into my life as Sunil (Kabhi Haan Kabhi Na), as Raja (Deewana), as Raju (Raju Ban Gaya Gentleman), as Raj (Dilwale Dulhania Le Jayenge), or as Rahul (Dil Toh Pagal Hai); it doesn’t matter. He entered and stayed. In my heart, of course, but also in my head.

From ages five through nine, I was living through a dark period of sexual abuse. An overwhelmingly difficult and confusing time, occasionally made brilliant by films, especially those starring SRK.

Struggling with trauma, my mind confused violence for love, as do many abuse survivors. I imagined my older self marrying one of my abusers. That twisted script was a coping mechanism. SRK rewrote it for me. The love and care he lavished on his heroines slowly changed my language of love. In an interview, Shah Rukh spoke of why he loves his work—because it makes people smile, even if for a brief moment.

Shah Rukh made me smile. He made me giddy with joy.

More revealing was his interview with Farida Jalal. He said that his audience either want to be fathered by him or they want to mother him, but rarely marry or date him. Even if this is a sweeping desexualisation of the desires of young girls and women, it was true for me. I never fantasised about SRK. I wanted to marry Hrithik Roshan, Fardeen Khan, Rahul Dravid, and also Yuvraj Singh at some point. But never SRK.

Perhaps because love, in my world, had always come with fear. Desire was something that hurt me as a child, so I sought comfort in a kind of love that asked for nothing in return. Shah Rukh made me believe in tenderness again, without the threat that usually accompanied it. His love was unmistakeable, unconditional and limitless. Unlike the chaos I was living with, SRK offered nothing but clarity.

He became the voice in my head that told me things would be all right, that I was doing well, and that I would come out on the other side as a winner.

This is why, years later, as a 30-something-year-old, SRK was back again in my life, this time, sitting next to me in the therapist’s office. The year was 2019; I was in the middle of writing my first book, It’s All In Your Head, M. I was going through a period of debilitating self-doubt. I hadn’t made progress in over six weeks. I was frustrated at how much I hated everything I was writing. It was a relentless cycle of writing and deleting.

When I told my therapist about this, she first explained to me the role of the inner critic. My mind, she informed me, created this negative presence to keep me safe, help me avoid danger.

But he has overstayed his welcome, she remarked. “Let’s get into a conversation with this guy,” she said. “And to start that, let’s give him a name.”

I, the child of Bollywood, named him Aamir Khan. “He has that annoying, perfectionist vibe, like Aamir,” I said. Then she asked if there was a voice that comforted me? This was an easy answer. “Shah Rukh Khan,” I responded. She smiled and asked me to write a letter to the critic, Aamir. “Make it in the voice of Shah Rukh, thanking him for protecting you, asking him to retire from this role.”

I rolled my eyes hard at this request, but wrote the letter anyway. She always made me do quirky things that ended up being helpful. Unsurprisingly, it helped. SRK silenced the angry Aamir voice. In the following months, I finished writing my book. Hearing comforting things in his voice, even if the words were mine, helped put things into perspective.

In her book, Desperately Seeking Shah Rukh, Shrayana Bhattacharya writes about the women she interviewed for her research, “These women relied on Shah Rukh when they found the real world and all its pandemics and practicalities inhospitable. Because only the deepest dissatisfaction with reality drives us to dwell in fantasy.”

I found language for what I had been doing my entire life in these two lines. In periods of deep despair, when leaving the bed was difficult, when my breath was being held ransom by panic, I would turn to Shah Rukh. Play a scene from a film, or simply watch an entire film of his. Running into his open arms was the cure for my anxieties.

I remember a time when I was maybe ten or eleven. Dil Toh Pagal Hai was playing on TV. I wanted to watch it. My brother and I got into a fight. He wanted to change the channel. Aai was in his favour because this was the Nth time I was watching the film. When they took the remote from me and switched the channel, I ran to my room and burst into tears. I have always disregarded that memory as childish stubbornness.

But in hindsight, perhaps it was never about the movie. I was a traumatised child who just needed SRK to hold my hand. He, after all, was love without danger, affection without demand; the kind that held you without touching.

As a grown woman in her 30s, I don’t need him to hold my hand anymore. But that doesn’t mean he’s gone. His voice lingers on screen, in my silences, in the sentences I write, and in the quiet ways I choose to remain. He gave others a language for longing, he gave me a reason to stay. This, however, isn’t the end. As the man within my head often says, “picture abhi baaki hai, mere dost.”

souk picks

souk picks