The revolution will not be televised

Editor’s note:

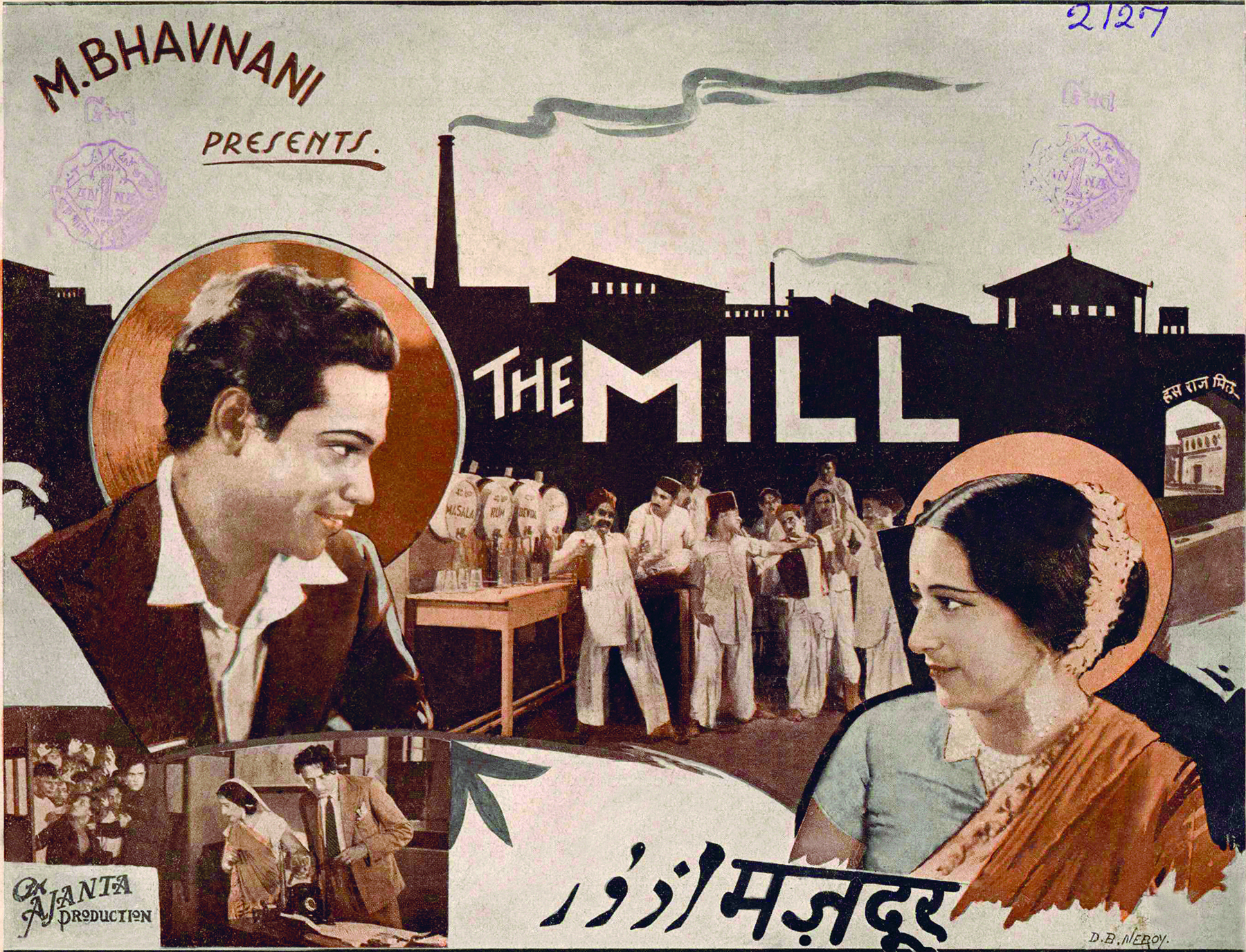

The Mill, or Mazdoor, was a much-anticipated film in 1934 that led to bourgeois anxieties about unruly audiences. The filmmakers were locked in a five-year battle with censors. There were fears that cinema—especially the anti-capitalist and anti-racist kind—could instigate the workers, the youth, and the working woman, leading to mass uprisings. Cinema, thus, was recognised as a site of political protest. It allowed the audience to experience the sights and sounds as a collective.

This excerpt — from the chapter ‘Visualizing the Urban Crowd Political Spectatorship in the Age of Cinema’ by Debashree Mukherjee — and images have been taken from 'Photographing Civil Disobedience, Bombay 1930-31'. The book is published by Mapin Publishing along with Alkazi Collection of Photography and is in conjunction with the exhibition ‘Disobedient Subjects: Bombay, 1930-1931’ at CSMVS (in partnership with Alkazi Foundation) in Mumbai from October 11, 2025 to March 31, 2026.

*****

For more than two decades, the India Office in London had been petitioned by angry film viewers, religious leaders, journalists and politicians who objected to sensitive content in both Indian and foreign films, and by those who sought the proscription of films that were racially or religiously offensive to Indians. By the late 1930s, a vibrant and heterogeneous film audience was in place, one that recognized the social effects of mass media and treated cinema as a site of political protest. At the same time, bourgeois anxieties about unruly audiences who could be instigated by nationalist, anti-capitalist or anti-racist film messaging overlapped with anxieties about workers’ unions, urban Muslim youth and the middle-class working woman. Let us consider an example from this decade as an illustration.

In 1934, a highly anticipated film titled The Mill or Mazdoor (trans. Worker) was made in Bombay, scripted by the acclaimed Hindi novelist Premchand and directed by Mohan Bhavnani, a veteran filmmaker. The Mill’s plot was extremely topical: a love story between a millowner’s daughter and a trade union leader, which presented a romantic solution to Bombay’s decades-long labour agitations against the powerful textile industry. An added attraction of the film was the fact that it was shot on-location at Bombay’s Hansraj textile mill and promised realistic footage of workers’ rallies and strikes. However, The Mill was immediately proscribed and the filmmakers were subjected to a five-year-long battle with the censors. The main fear was that because it graphically depicted violent proletarian resistance to capitalist exploitation, the film would cause unrest in the city.

In 1934, a highly anticipated film titled The Mill or Mazdoor (trans. Worker) was made in Bombay, scripted by the acclaimed Hindi novelist Premchand and directed by Mohan Bhavnani, a veteran filmmaker. The Mill’s plot was extremely topical: a love story between a millowner’s daughter and a trade union leader, which presented a romantic solution to Bombay’s decades-long labour agitations against the powerful textile industry. An added attraction of the film was the fact that it was shot on-location at Bombay’s Hansraj textile mill and promised realistic footage of workers’ rallies and strikes. However, The Mill was immediately proscribed and the filmmakers were subjected to a five-year-long battle with the censors. The main fear was that because it graphically depicted violent proletarian resistance to capitalist exploitation, the film would cause unrest in the city.

The censor’s paper trail reveals some locational specificities of Bombay city that caused these acute apprehensions—its changing demographics as the foremost centre of trade and industry in the region, its status as the centre for Communist Party activities, and its reputation as a city of strikes—all of which were only possible because of the emergence of a new historical figure with a reflexive class consciousness, the girni kaamgaar, or more broadly, the mazdoor.

Statistics from this period show that Bombay audiences constituted a big chunk of who was watching Bombay films, with a 33–47% share in nationwide theatrical revenues. This local film viewership depended heavily on working-class audiences solicited in theatres built in cotton-mill neighbourhoods. The Mill’s censors were therefore not simply speculating about an imagined working-class audience, they were also envisioning the actually existing proletarian film publics of Bombay who seemed ripe for radical socialist messaging.

Statistics from this period show that Bombay audiences constituted a big chunk of who was watching Bombay films, with a 33–47% share in nationwide theatrical revenues. This local film viewership depended heavily on working-class audiences solicited in theatres built in cotton-mill neighbourhoods. The Mill’s censors were therefore not simply speculating about an imagined working-class audience, they were also envisioning the actually existing proletarian film publics of Bombay who seemed ripe for radical socialist messaging.

I suggest that the rise of Bombay’s mills and the new-media context of rapid mass reproduction and dissemination historically converged to produce a “perceptual machinery of the collective” wherein visual technologies such as photography and cinema were rapidly enlisted to address the collective and, at the same time, represent the collective. Cinema in Bombay at this time thus rose to the occasion and visualized the new proletarian collective, romantically individualized into the icon of the mazdoor. But, and this is important, cinema also provided the perceptual training of seeing like a collective. As the urban masses gathered in the darkened anonymity of a movie hall, they were sensorially trained in the perceptual art of seeing like a collective—gasping, laughing, cheering, crying in a shared affective moment. This mass affect, produced by the movies, had the potential to incite as much as to educate, and elite interests recognized this ambivalent potential almost immediately.

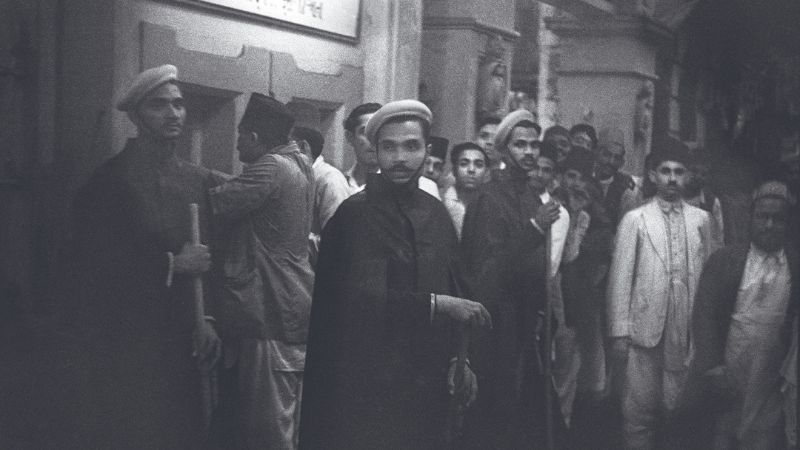

My argument is that the spectating crowds we see in the Nursey album are oriented towards the compelling scenography of outdoor street rallies and political processions in a way that is similar to their orientation towards the filmic image inside the movie theatre. There is a direct overlap between the demographics that would throng a film screening and those who crowded the streets as loiterers, workers, vendors, shoppers or commuters. The screen calls a collective into being by addressing strangers and drawing them into a shared embodied experience. The political procession or other protest spectacles from the 1930s similarly craft a public out of the amorphous crowd. Like the rally-watcher, the moviegoer intuits, quite viscerally, that a group affect has been created by the spectacle, a kind of energetic pact that pulls the individual out of solipsism and into the collective.

My argument is that the spectating crowds we see in the Nursey album are oriented towards the compelling scenography of outdoor street rallies and political processions in a way that is similar to their orientation towards the filmic image inside the movie theatre. There is a direct overlap between the demographics that would throng a film screening and those who crowded the streets as loiterers, workers, vendors, shoppers or commuters. The screen calls a collective into being by addressing strangers and drawing them into a shared embodied experience. The political procession or other protest spectacles from the 1930s similarly craft a public out of the amorphous crowd. Like the rally-watcher, the moviegoer intuits, quite viscerally, that a group affect has been created by the spectacle, a kind of energetic pact that pulls the individual out of solipsism and into the collective.

souk picks

souk picks